notes for a performative lecture

I go on a ten-day silent meditation retreat. I return. A friend asks me what it was like. I say that if I was an actress it would be a great way to prepare for a part. He asks, “Why?” I say, “When you meditate for that long parts of you disappear – there’s less ‘you’ to get in the way, more space for something else to come in” (that’s a guess; I’m not an actor). He asks, “Have you ever read The Mystic in the Theatre?” I say “no,” and then I read it. It’s about the life of Eleonora Duse. She meditated. I also learn that Duse and I are interested in the same medieval mystics.

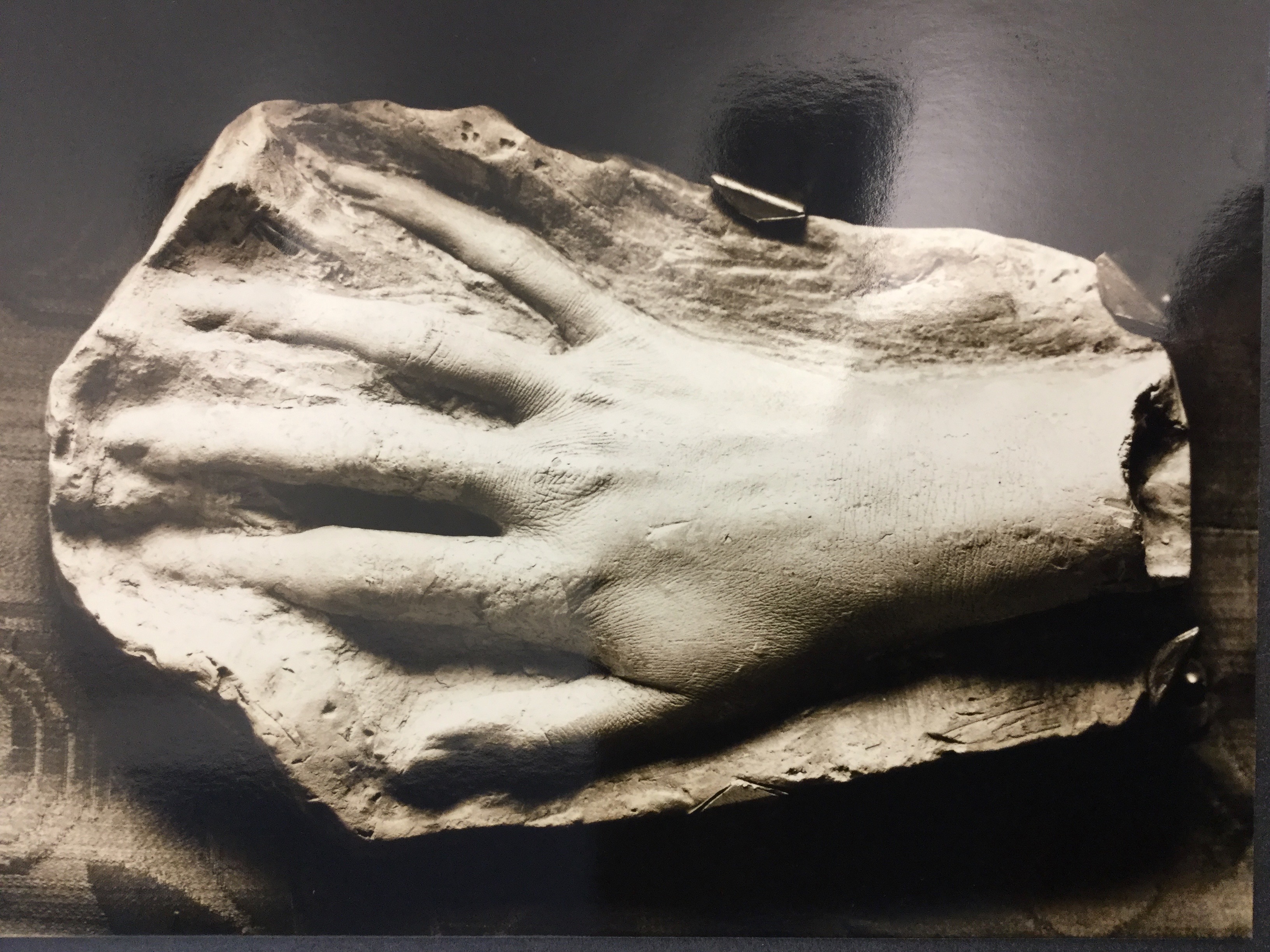

In the archive I become obsessed with her hands. It’s not hard to see why. Everyone was obsessed with them. But critics and audiences had actually seen them, or were transported by them, or healed by them, or felt heard by them. What was it, exactly? And now I’m wearing an archivist’s white gloves and taking digital pictures of a photograph of a plaster cast of Eleonora Duse’s right hand.

She was an Italian tragedienne. She was the first modern actor in the Western World. She played the transitions, acted between the words (most often the words of terribly written plays). She was not afraid of silence. She was said to shape-shift before audiences. By all accounts, she was a shaman. Duse’s superpower: her capacity to disappear, leaving only her plaster hands as evidence that she was a material presence in the world. Disappearance. Reproduction. She knew the theatrical drill.

She leaves the stage in 1909. “To save the theatre, the theatre must be destroyed,”[1] she says in 1912.

May 1915: Italy enters World War I. Duse refuses to entertain the troops on the frontlines. She goes instead to sit with the soldiers – writing letters for them, holding their hands, delivering packages, listening. She stays in a hotel close to the warfare during one visit. When she returns, her hotel is a pile of rubble. Bombed. Her timing was always impeccable.

Letter dated 15 December 1915, to Enrichetta, her daughter in England who we now have evidence was a British spy: “I have done everything in life between one departure and another —the heart has remained motionless, turned toward that suffering, that light, that thing that is everything and that is nothing.”[2]

This is what I am after, I think, as I follow her hands. Evidence of where theatre is really taking us, has always taken us.

Duse studies the new “silent medium” (her term): “All is seen, experienced: documents, evidence in hand – a news item. The exterior of a poor life, displayed by machine, every evening the same way.” “Nothing of what is not seen and weaves a life.”[3] The first moving images on cinema screens display a terrifying number of corpses, sentient and celluloid. What to do with all of those missing bodies?

To Enrichetta, June 1916: “the realization of film is a spiritual problem.”[4]

Medieval art is the answer to her spiritual problem. Another language for connecting with missing bodies (?). 1916, Duse films Cenere (Ashes). She treats filmic images like tableaux vivant, living pictures (or corpse pose?). Duccio’s “Descent from the Cross” (ca. 1308-1311) and Giotto’s “Lamentation” (1306) find their way into the film.

We teach students that theatre is reborn in the churches of medieval Europe. For all we know it is reborn a thousand times in a thousand places during those pesky “Dark Ages.” This time, though, theatre is reborn through a popular musical number about a missing body. “Whom do you seek?” the angel sings to the Marys (usually three, but this is negotiable). “Where’s Jesus?” they sing back. “He’s where he said he would be: not here, but not not here,” the angel belts out before telling them to spread the good news.

Disappearance. Reappearance. Disappearance. Reappearance. This death does history like theatre. Duse patiently wrings the very life out the dusty tragedies she performs to play with a death like this. When she does, her audiences follow her hands all the way to oblivion. “Life is not cinema,” she writes to Giorgio Papini.[5] Neither is death.

In 1918, Duse tests positive for the “Spanish Flu.” (Federico Garcia Lorca later writes of her duende, play and death her forte.) She survives and returns to her plays in 1922. She needs the money. The theatre had not died, but it most definitely kills her.

April 1924: Outside in the rain, unable to get in through the locked stage door. Drenched. First influenza. Then pneumonia. She dies at age 65. In Pittsburgh. She is performing Marco Praga’s La Porta Chiusa, or The Closed Door. Play and Death.

To Enrichetta, 1917: “You who live in a high intellectual environment, do not believe that your mother follows the Church, or chooses the Middle Ages just because I have chosen something from the thirteenth century. Not at all. On the contrary, it is very modern, as everything recurs, wars, illnesses, beauty and ugliness, greatness and the stupidity of the world.”[6]

Image use by permission of University of Glasgow Library, Archives & Special Collections.

[1] Qtd in Symons, Arthur. Eleonora Duse. London & New York: Benjamin Blom, 1927, p. 3.

[2] Qtd in Weaver, William. Duse: A Biography. London: Thames & Hudson, 1984, p. 301.

[3] Qtd in Weaver, William. Duse: A Biography. London: Thames & Hudson, 1984, p. 305.

[4] Qtd in Pagani, Maria Pia “Duende Has No Age,” in Eleonora Duse and Cenere (Ashes): Centennial Essays. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2017, p. 94.

[5] Qtd in Vacche, Angela Dalle. Diva: Defiance and Passion in Early Italian Cinema. Austin: U of Texas, 2008, p. 138.

[6] Qtd in Sica, Anna & Alison Wilson. The Murray Edwards Duse Collection. Milano: Mimesis Edizioni, 2012, p. 97.