02

Australia

Australia is haunted land – it is haunted by colonialism, by climate change, by refugee crises, and by crises of collective will. The pieces in this issue offer sites of resistance, with a particular sense of irreverence for the proprieties of conservative culture – a desire that may reflect a national subconscious – to undermine, to laugh, and to play with seriousness. Edited by Peter Eckersall, Helena Grehan, and Nicola Gunn.

-

Peter Eckersall

Editors

Helena Grehan

Nicola Gunn

Theatres

- 1.All the Worlds

- 2.a game for world leaders to play

- 3.Nearly Finished

- 4.Now You See Me

- 5.Scenes of Appalling Human Degradation

- 6.Edits to be Performed

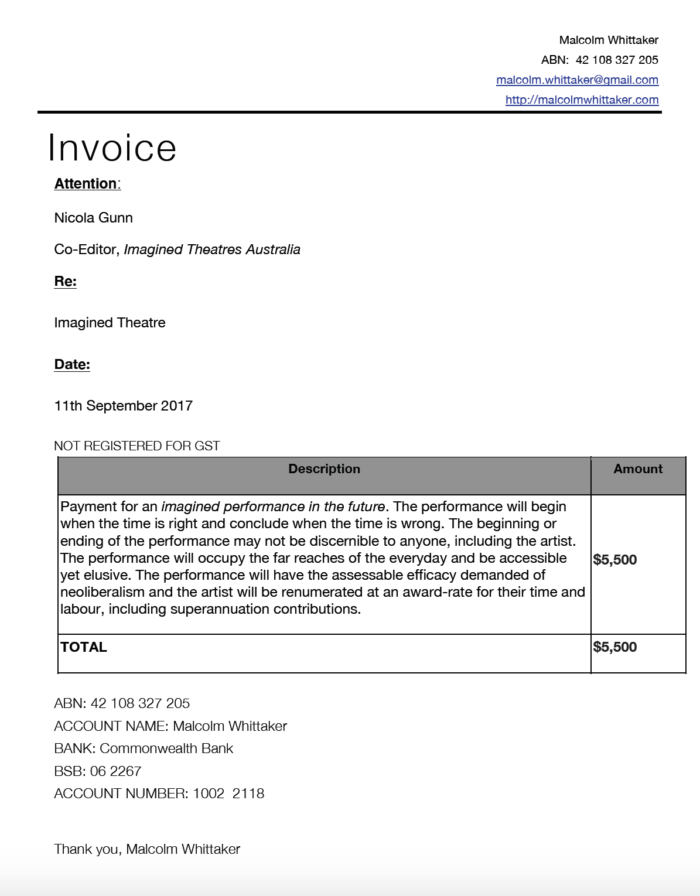

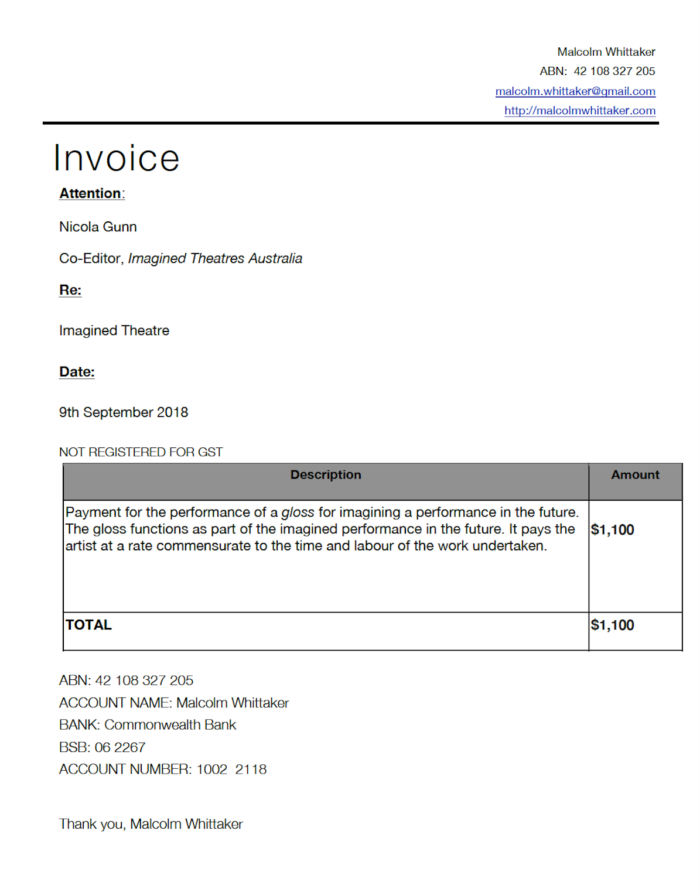

- 7.Invoice

- 8.One-scene-one-person-one-song-musical

- 9.Uncle Vanya in Krivina: playing near two rivers

- 10.Seance

- 11.Blind Bats in the Belfry

- 12.The impossible possibilities of decolonization

- 13.Theatre of the Everyday

- 14.This is Me

- 15.A Hooligan Reflection

Prologue

Hauntings, Veneers, and Irreverence: Imagined Theatres in Australia

… the veneer of civilised societies is very thin, a fragile thing that once broken brings forth monsters. (Flanagan: 2018)

Australia is haunted land. It is haunted by its inability to come to terms with its colonial history and by its continual refusal to acknowledge the place and significance of the First Nations Peoples. It is haunted by the spectre of climate change and the complicity of its corporations in obfuscating this reality. It is haunted by the monstrous apparatus that incarcerates refugees and asylum seekers in far-away locations – out of sight, in what Giorgio Agamben argues are ‘states of exception’ (2000: 40). It is also haunted, as are many ‘advanced’ societies, by a consumerist culture that that celebrates individualism over the collective. So, in this context then, the arts, as a space in which resistance emerges and alternative ideas are proffered, are vital. The arts, broadly speaking, are the conscience of the nation at a time when this nation, at least, desperately needs one. They refuse to be complicit and seek to open up landscapes of possibility: imagining alternatives to the status quo.

Whilst they offer sites of resistance, they do this in the Australian context with a particular timbre. There is something peculiar perhaps, about the ways in which artists in this country engage with and respond to the political context they find themselves in. This is characteristic of all art forms but is particularly evident in the context of live art – theatre, performance, and comedy. There is a sense of irreverence for the proprieties of conservative culture – a desire that may perhaps reflect a national subconscious – to undermine, to laugh, and to play with seriousness. This in itself is a key element of the refusal of complicity.

The striking thing about the collection of voices represented here, is the depth of their capacity to participate in this process of re-imagining: nation, land, people, ecology, being, and politics and to do so with thought, care and at times a smattering of the absurd.

The contributions to Imagined Theatres: Australia represent a diversity of theatre forms that reflect the breadth of activity being undertaken across the nation. They demonstrate that the idea of an Australian theatre is always evolving and therefore incomplete. Historically and up until the present day there has been a resistance to the idea of a single national theatre culture. Theatre is dispersed, and it has always intervened from a range of vantage points in the diversity of the nation – responding to stimuli from culture, politics and society. Given the size of the country and the vast distances between sites – the kinds of theatre work being developed include both the intensely local and also work that responds to and engages with global concerns.

Responding to the structure of this project, where one text is in dialogue with a Gloss, is a very interesting experience for Australian theatre, where the question of arts criticism and its place in the performing arts has an ambivalent history. Current responses notwithstanding, and with the valiant exception of RealTime (rest in peace), there is a strong history of resisting the critical paradigm in the arts. This has been exacerbated with the demise of mainstream arts journalism. The rise of new critical models such as this site and that of Witness Performance (https://witnessperformance.com/), amongst others, are heartening and play a crucial role in both revitalising the discourse and in opening up new ways of thinking about and responding to the arts.

We have really enjoyed assembling this provocative, witty, and significant collection of responses to an imagined theatre and we hope that it will give you, as readers, as much joy as it gave us, as Editors, during the construction and curatorial phases. We thank all of our contributors for their enthusiasm, care, and unbridled creativity.

Peter, Helena, and Nicola.

References

Giorgio Agamben. Means Without End: Notes on Politics. Translated by Vincenzo Binetti and Cesare Casarino. University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 2000.

Richard Flanagan. “Our politics is a dreadful black comedy.” The Guardian, 18 April, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/apr/18/richard-flanagan-national-press-club-speech-full-politics-black-comedy

-

Imagination is a theatre of sorts.

It begins in protean darkness. Memory and invention wind around each other like strands of DNA, birthing monsters and angels, the never-to-be-born and the long dead, the impossible and the unrealised. In this place nothing has edges: interior contemplation and worldly experience are fragmented narratives of feeling, functions of memory. The physical senses morph into metaphors of themselves, so that smell and colour and touch and taste are interchangeable languages, allusions that indiscriminately summon the past, the present, the future, abolishing time.

I have no visual imagination, so this theatre is a place of rhythm and touch, of connections that articulate themselves through webs of feeling. They shape themselves into words. I have no idea when words became my primary means of making meaning for myself, but I do know it started very early. I sometimes wonder how much this restricts what it is possible to think. There are many ways of articulating thought.

On this stage without images I play the subconscious dramas that become my understanding of whoever it is who manipulates these words, the part of me that is the writer. My understanding is always partial. I can’t perceive the mechanisms that impel the narratives, that bring this memory to the surface but not that one, that insist on this colour of feeling but not the other.

Much as I dislike the mystification that often attends thinking about imagination, this process is almost entirely obscure to me. I loathe the ideas of divine inspiration or the muse, but I understand why artists invent them. Something happens that resists the conscious mind. The moment of articulation into form occurs inside a black box that remains closed.

I might be able to trace an originatory thought, a moment when an idea occurs; I can certainly measure the labour that occurs afterwards. But the movement that translates intellectual memory, sensory impulse, conscious and unconscious thought, or the vague shape of feeling into a formal outline, a narrative, a poem, an articulated thought, always eludes me. I have no idea what it is or how it works.

This theatre of imagination is peopled and multiple, as dreams are: so many ghosts, so many memories. It bears the imprints of every conversation I’ve had, every tweet and poem, every play and sculpture and tree, the view from every window I’ve looked through, the smell of every animal I’ve touched, human or non-human, all the scars of pleasure and pain. But it is solitary. I am the only audience.

The theatre I imagine, on the other hand, is full of people. Each person brings their own theatre of imagination, their own private, inarticulable galaxies of connection and feeling. In this common space, the galaxies begin to dance together in the joyous gravity of performance. The heat of our breath warms the air and permits our bodies to relax into their natural permeability, freed at last of the armours that separate us from each other.

We know in this space that we are not discrete and separate, but fountains of flesh making and remaking ourselves through infinities of possibility, each different from all the others, yet vibrating in harmonies of meaning. We become ourselves by becoming other, strange and familiar at once. Time is suspended in the music of continuous becoming. The past and the present and the future are all singing in our common breaths.

I have been in this theatre. Sometimes for a moment, sometimes for a long series of moments. It begins in darkness, sometimes, and sometimes in light. In this theatre there are images and sounds, the inhaled breath of others that enters my memory, changing me again. Perhaps they will become words. Perhaps they will remain unworded, beautiful reminders of all the worlds that are not me.

About the Author

When words and phrases formulate themselves in my mind, I occasionally sense I’ve been visited by divine inspiration. Language is outside me and floods itself into my consciousness. I am the docile audience for life’s forces. I watch paragraphs take shape. Other times, though, I am a world-maker: sentences are sutured together deep inside me and I firmly, aggressively, choreograph their dance.

‘Imagination is a theatre of sorts,’ writes Alison Croggon. Her reflections offer us a thinking-through of thought-making, thought-creation; a play between memory and invention, how feeling shapes itself into words. For some artists, imagination is visual: ‘thought is so much closer to image than to language,’ reflects ‘Vita’ in Ceridwen Dovey’s novel In the Garden of the Fugitives. Not so for Croggon. Croggon’s internal theatre is ‘a place of rhythm and touch,’ it ‘bears the imprints’ of every conversation, every experience, she has had. She offers us a meditation on consciousness, how a mind makes itself apparent to itself.

But the spaces Croggon describes are not always solitary. She imagines a peopled one too, a meeting of multiple minds, multiple theatres of imagination, ‘inarticulable galaxies.’ She writes: ‘we become ourselves by becoming other, strange and familiar at once.’ There are images and sounds in this theatre, and sometimes there are words too, but not always. For Croggon, she finds herself extending out towards others, a never-quite-reaching, residing in places of the perpetually-unknowable, ‘beautiful reminders of all the worlds that are not me.’

About the Author

-

“had leaders shown more solidarity, empathy and compassion to their people, we would have much less conflict at this time. that is why I have been urging leaders: please put the public common good ahead of everything else, ahead of your personal, narrow or regional perspectives.”

ban ki-moon, u.n secretary general 2007 – 2016

‘a game for world leaders to play’ is a permanent vr escape room[1] which has been installed in an underground bunker in the hague. in collaboration with the hague institute for global justice, the escape room offers a period of radical professional development for world leaders to explore the consequences of their decision making, alongside the citizens who will be directly affected by it.

world leaders receive an exclusive invite which outlines major areas of concern in relation to their leadership style and policies.

part boot camp, part active problem solving, ‘a game for world leaders to play’ is an immersive social play experiment themed around 21st century survival. a small group of citizen players join one world leader for up to 24 hours. all global citizens are eligible to apply, then shortlisted to their leaders country and submitted into a sortition[2] process ensuring an equal spread of race, gender, social status and political ideology.

they put aside their personal and political preferences in favour of collectively problem solving global catastrophic risks that threaten the existence of humanity. an expanded online audience can view their sessions via embedded media and can input their suggestions and strategies directly into a curated vr feed sent to all players. issues on the menu range from climate change, to terrorism, economic disparity, to rapid population growth. each vr experience transports players into a 3d environment to problem-solve. they are clothed in wearable vr ‘smart’ suits which constantly monitor their physical and mental welfare. players don their high-tech onesies and wireless glasses, enter each escape room door, and may find themselves on-board an overcrowded boat, inside a fully automated shipping warehouse, on the foreshore of a southeast asian sunken city, or at the foot of a mountain of gmo seeds.

each room posits a not-too-distant dilemma to solve based on the future trending forecasts from quantumrun[3] and demands a collective solution be reached democratically within a given time limit.

during the experience, world leaders get the opportunity to reconnect with their constituents as well as their own ethical compass. each citizen player is empowered to contribute ideas and solutions which could carve out a road map for a sustainable utopian future.

first world leader selected: oprah winfrey, the 46th president of the united states

first escape room session: nov 2028

[1] an escape-room is a physical co-operative adventure game in which players are pulled into scenarios akin to a movie or computer game. they unravel carefully plotted puzzles using clues, hints and strategy with a limited time-frame to find their way out of the space.

[2] sortition, was a form of ancient athenian democracy whereby public representatives would be chosen by lottery as a means to avoid the corrupt practices used by oligarchs to buy their way into power.

[3] quantumrun.com researches and reports on the latest revolutions happening today in technology, science, health, and culture, but through a futurist’s perspective.

About the Author

disclaimer:

we never felt as though we belonged to the world of theatre. preferring to couch our practice in participatory performance and public intervention. the artform lineage we fell in love with 20 years ago slipped somewhere between political activism, live art, and experimental practice. we always saw it as a stunningly audacious creative home with no walls and the freedom to take risks and we liked it that way. it allowed us to situate ourselves outside on the streets, gave us license to misbehave with form and content and, most importantly, it led us to think about the deeper potential of audience as our creative comrades, not as spectators but activators; like sleeper cells waiting for a phone call as their trigger to sneak outside and turn the world upside down.[1]

play, as in games, is our weapon of choice. we use games to encourage participation and as a thin veil to get away with some collective sly mischief. in the guardian online article ‘20 predictions for the next 25 years’[2] jane mcgonigal imagines a future where games serve a social purpose beyond entertainment, enabling problem solving through cooperative play. could playing a non-competitive board game offer a framework towards implementing a universal basic income? could playing an escape room scenario offer a solution for the geo-politics of climate change? could immersing yourself in a vr minecraft experience help explore the ethics around in-vitro meat and synthetic foods? games as a tactical tool for critical enquiry into real world issues excites us a great deal. as we project our imaginations into this future we see the possibilities of new technologies undermining old forms of cultural, political power and a seismic shift of belief in the value of creativity to tackle major systemic problems. we see a new politic of collaboration based on the collision of skill sets from across industries and sectors. we see bold acts of civic improvement through civil disobedience with citizens directly affecting the change they want to see. we see ourselves on the front line with them.

‘a game for world leaders to play’ is an impossible work we would dearly love to make. perhaps not right now but at some point in the next 25 years. getting it out of our heads conceptually has been a lot of fun. we hold onto this imagined work with an equal degree of fear and excitement, the best combination of feelings when trying to make new work.

[1] pvi collective are anti capitalists and don’t use capital letters

[2] 20 predictions for the next 25 years, no. 10, gaming: ‘we’ll play games to solve problems’ – jane mcgonigal, the guardian, 11 january 2011, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2011/jan/02/25-predictions-25-years.

About the Author

In Sickness and in Health.

I think theatre is sick.

Or is it our leaders who are sick?

Like you, I never felt that I belonged in the theatre, but then nor was I for the street. I have always been a little bit afraid of theatre, or bored by it, but I think I am more afraid of the street.

A tendency to shyness and/or the history Modernity has bequeathed me a fear of being found loitering – a woman in the street is a figure of ambiguity. Call me old fashioned, but I don’t want anyone asking me what I am doing here, all alone.

Is that why I cannot belong in theatre? Why I have to burrow into my books?

But after reading pvi I am not quite done with live art. Really alive art. I am thinking that there could be a theatre of the inner body – not some kind of fake simulation, but an investigatory theatre of the lungs, the bones, the bowel, the heart.

This is not a new move of course. There have been journeys into the body in theatre and performance. Artists have swallowed tiny cameras; an eye on the end of a tube has gone in search of illuminated polyps projected onto gallery walls. There have been surgical events in the gallery – incisions, facelifts, implants. Much has been made of tissue cells and sutures, of magnifying glass.

But I lack confidence in this body as theatre. I have little faith, but a smidgeon of hope – for example, I will never stop hoping that I might see my father again, although he is dead 10 years this September.

Is that too much to hope? After all, theatre likes to deal in fake characters, idée passé. Maybe theatre can bring my dad back, clad him up in his thick grey suit, tie his tie and lace his shoes and prick him and poke him … and, well, push him out on stage, where he will have to watch where he steps because he has a bad leg because of a hemiplegia from a botched operation on his brain a very long time ago. (I remember the uneven seam arcing across his cauterized skull, like a fault in the ground. The soft left side of his face sliding downwards, like a collapsed cliff.)

I am not quite sure how theatre will bring back my mother. How will she enter? A shift in genre? Stage left on a palanquin with her four children upholding her? Or will she totter in on heels, already tipsy, diaphanous, her curls stiff with Schwarzkopf spray?

I like the idea of a palanquin. There are some people – families, for example – who need to hide things. I am all for a theatre of the interior, for a theatre of stealth and thievery.

I do like your games, pvi, and I believe The Hague is almost ready for such a proposition. But first we must determine the health of these World Leaders of ours.

I have outlined my suggestions for interior investigation below.

But they worry me, these games of ours. In what modality will we play them? Are we allowed to laugh? Is this serious play: I dare you to touch the electric fence.[1]

MRI: A game for world leaders to play

The intention is exploratory. What will we find? And in the world of medical over-servicing, there is every chance we will find something.

- Take off all your clothes and put on the pale blue gown (arms first/tie at the back).

- Put on the headphones and lie on the table. You must remain very still, as the machine is extremely sensitive to disturbance.

- Don’t worry about those heavy lead weights on your lower limbs; they will hold you still in case you want to get up and leave.

- Don’t leave.

- And don’t look around. I can assure you everyone is represented, and they are all hearing the same thing, more or less.

- I have to say, some of you look very small and old without your clothes. The body is so much more insubstantial and yet more real in the flesh. How can that be?

- The women – there are a few – are the most at home in their gowns.

- Keep still, please. We are now going to raise the bed on which you are lying and press a button to move the platform into the magnetic resonance imaging machine. The strange pulsing noise you hear inside the tunnel is not the sound of some alien invading force bent on world domination – fingers off the button, now! – but the sound of hydrogen atoms emitting a radio signal which is measured by a receiving coil. I assure you, everyone is hearing the same thing.

- We are looking for dis-ease, for something malevolent, terminal, something that will cause you to falter, something that will render you unfit for the job ahead.

- Chances are we will find it.

- Here we go.

- Some of you are shaking. One or two are crying. Why are you so worried? You are all in this together. You could have talked to each other in the change room; you could have exchanged nervous pleasantries, put each other at ease, agitated for a collective protest to such invasive procedure, refused to undress. But you chose not to.

- And now look where you are: all alone in the scanner.

- And it’s not looking good.

[1] Eisen, G., 1990. Children and play in the Holocaust: Games among the shadows. Univ of Massachusetts Press.

About the Author

-

I’m standing in a queue waiting to get into my own show. The queue is a long line that loops around, resolving itself in an ellipse. I have audience members in front of, behind, and across from me, though not so close that I can touch them.

Each of us is holding a ticket that is alive, splashing a kaleidoscope of colour onto our faces and torsos. It’s all shape and form and angles, hard to read and designed for experience-only. Slowly, the moving images pixelate and reassemble into a three-dimensional holographic theatre environment, only now we’re in Zagreb where my artistic partners are co-presenting our artwork, which is immersive, transportive and telepathic, and all the codes of theatre have been re-programmed and re-configured and it’s hard to say whether it’s narrative, or genre, or media, live, pre-recorded, projected, ingested, because we’re in a deferred space, well at least our bodies are because they’re still in Melbourne but the rest of us is in Zagreb and, because it’s an avant-premiere, the audience is chock full of presenters, friends, supporters, bureaucrats, and donors who have ‘come’ from all over Europe, all over the world, only no one’s left their lounge room, office, bar, or whichever location they choose to enter the ‘performance’ from. It’s quite a rollercoaster, this show, until it stalls, stops, and then surrounds you like a meditation. One deep, long, sustained breath, exhale, and it’s over.

I let the turning turn into a low hum, warm my voice, and walk onto a dark and empty stage. I click on the only light in the space, a naked globe, small enough to hold in my hand and I say to the audience, “Finished, it’s finished, nearly finished, it must be nearly finished…” (or some such awesome quote from Sam B). It’s clear they don’t know what to make of it, whether it’s part of the show in Zagreb or the beginning of the show in Melbourne, and neither do I ’cos we’re all stuck together in a liminal space between the tenses, past, present, future, provisionally altered and manufactured by our collective resistance to understand where we are, what we’re doing, thinking, and feeling. It has to end of course, sanity insists on it, and all of a sudden everyone and everything has dissolved but me and Samuel who says nothing, just drills me with that quizzical baby-blue stare, waiting for the moment to strike a non-verbal blow to my sub-conscious, to prompt me into remembering his lines from whichever of his writings I’ve filed away but nothing happens. Nothing happens! Nobody comes, nobody goes, try again, fail again, fail better. Nothing happens. Bugger. Words are all that we have. What is that unforgettable line? Oh yes. The end is in the beginning and yet you go on. Audience applauds, or would, if they were still there.

About the Author

Notes from the floor

(Transcribed from the sound designer’s notebooks, final rehearsal, date not marked)

So, we’re on the floor for this new show. Not new because it hasn’t been done. A new type of show. The start time is translated for the 37 global time zones, but we can’t actually run the show – we’ll just slip side-ways from where we are (meetings, email, home, commuting, reading, talking, making) to where we’ll be to start be-ing. And there’s a huge spatial sound design.

In a satellite lecture for ACMI, Peter Weibel was asked ‘What is the future of cinema?’ He starts, “When images are transmitted directly into the brain … oh, but that would be sound.”

So, we’re running a 48 channel system through the space and the audience sit on a mesh floor above eight of the loud-speakers. The others sit on three levels around and above the audience, concealed inside the shadow lines. We can produce vistas, point sources, and project sound images into the minds of the audience. It goes black and I track David’s footsteps over the stage. Glad we changed his shoes to leather so we can hear his path, and the cue; his final steps crunch into a recessed tray of sharp pebbles layered over a resonant box. The 12 miniature blue-tooth microphones in the tray shoot off every footfall or shuffle into granular lines we process and spatialise in the theatre.

The mics across his body amplify every breath, rustle, or shift in position. The audience can barely see him, but his body extends to their ears. It’s intensely intimate with no space between us – just a shared sound-filled presence.

On-line a binaural mix from the theatre – the pebbles, the body mics, his voice, the spatialisation – is projected in a stream for headphones and a multi-channel mix for spatial sound systems in theatres, arts spaces, and museum spaces around the globe.

Since 2018 we’ve worked as a sonic-spatial ensemble: 2 source navigators, 4 spatialisers, and a spatial director. We rehearse in semi-darkness enough to see the table of data-controllers and heighten our auditory imaginations to better auralise (think visualise) sonic geometries and landscapes. Each syllable of David’s voice becomes a volumetric entity. Orbiting morphemes from every word stay draped throughout the theatre.

The sonic bed lingers as sounds from the pre-show audience queue rotate in pianissimo layers through the theatre; a cough, a shuffle, a ‘hmm’, murmurs from people who were somewhere and are now here (hear?). Peripheral auditory awareness is speeding and my attention is like a still focal point. Each time dp tries a line from Sam B we snapshot the utterance and stream it to the sonic vortex building in the space. Our headphone mixer signals ‘gravity moment’; the sound makes it difficult to tell which way is up.

David keeps on with the Sam B syllables – each try, fail, try, drops another layer into the surrounds and this incessant movement drives to stillness.

About the Author

-

British artist Raymond Briggs, perhaps best known for his 1982 post-nuclear war graphic novel When the Wind Blows, said that when he wanted to depict a character grieving, he simply drew them with their back to the frame. This way, the grief expressed in the face of the character is for the viewer to imagine. It’s an effective strategy in inviting the reader to invest themselves in the emotions of the character.

I propose we take this on in the theatre. We would only see the backs of actors, never their faces. Aside from inviting further investment from an audience in a character’s emotions, it would also be a deliberate and radical departure from what all that theatre marketing tells us is the central tenet of the theatre today: the face of the actor. As humans, we should actively battle against this falsehood as it promotes our appearance as our best achievement.

This is not a new idea. In his book, The Aesthetics of Absence, Heiner Goebbels advocates for the deliberate exclusion of some theatrical elements from the stage (including actors) perhaps seen most keenly in his work, Stifter’s Dinge. Edward Gordon Craig and Antonin Artaud also spoke of theatres without people. And if we are to exclude the actor’s face from the theatre, maybe we should go further and exclude ourselves from appearing onstage altogether.

Perhaps in the age of the Anthropocene, where humans are actively disappearing many species from the earth, we should all voluntarily disappear from the stage. Make a pledge not to appear whilst simultaneously making it indisputable that we are doing everything else but appearing. Use sticks from the wings to tip over glasses of water. Tug at strings to pull out chairs for ghosts. Be in the building but NEVER be seen, no part of us.

Without the distraction of how we look, we may be able to draw our actions into sharp focus.

About the Author

WAYS TO LEAVE THE STAGE

Exit stage left

Disappear into a cloud of smoke

Fall back on your fallback career

RUN!

Get upstaged by something more interesting

Fade into obscurity

Walk off

Put a tack in your shoe so you walk differently. Siphon money from your bank account until it’s all in cash. Find a crowded city where you can rent an apartment cheap. Disappear into the crowd. Build a new employment history, starting with temp or construction jobs. Think of a new name. Start calling yourself this new name.

Miss your cue

Exit stage right

Insult someone in power

Be pulled apart by dogs

Be trampled by dinosaurs

Be pursued by a bear

Flee, vanish, go AWOL, take off

Quit

Don’t come on in the first place

Be a mediocre performer

Be mediocre

Blend into the background

Get into army camouflage

Get into the army

Withdraw

Go back in time

Abdicate yourself of any responsibility

Say sorry

Atone for your sins

Undo your wrongdoings

Un-fuck the world

About the Author

-

There’s a woman on stage wearing slender black trousers cut at the ankle, a t-shirt and a blazer, flat shoes. Very neatly dressed.

She’s very elegant. And she’s holding a piece of paper, waiting. A bald man with a scraggly beard comes on carrying a chair. She looks at the piece of paper and directs him where to put the chair down. He leaves. And then another bald man with a scraggly beard comes on carrying a chair. Not the same bald man. A different bald man. She tells him where to put the chair and then he leaves. So it would seem she’s holding some kind of floor plan and the chairs need to correspond to the floor plan because all these chairs are numbered (I didn’t tell you that) and they need to go in a very specific configuration. So all these bald men with scraggly beards–

(Now the reason for their baldness will never be revealed)

So all these bald men with scraggly beards come swarming out of this little room in the corner of the stage like beetles, carrying chairs, and there’s bit of negotiation and confusion because she has to make two concentric squares of chairs, one inside the other, and they’re all facing inwards and they’re all specially numbered. But oh! The floor plan. It’s upside down. The floor plan is upside down! So all the beetles have to rotate the two concentric squares of chairs 90 degrees this way and while this is happening the woman walks down to the edge of the stage and says

Avez-vous une invitation? Vous devez avoir une invitation. (She’s French. You need to have an invitation.)

Cette événement est privé. (This event is private.)

Vous devez avoir un billet. Avez-vous un billet? (You need a ticket.)

(And then she takes the curtain and starts drawing it across the stage, like so.)

Je suis desolé mais vous devez partie. (I’m sorry but you need to leave.)

About the Author

The title promises not just degradation but “appalling” degradation. Some potential spectators feel a frisson of anticipation and check their smartphone’s storage in preparation for the photographs they will take. “Pics or it didn’t happen,” as the saying goes though Instagram will likely delete these images, on the grounds that they are “violent, nude, partially nude, discriminatory, unlawful, infringing, hateful, pornographic or sexually suggestive” (Instagram 2018). Other would-be audience members recoil in anticipated horror, outraged at the implied violence and the invitation to voyeurism. Perhaps they will start a social media campaign and an online petition, demanding that the producers cancel the performance, issue an apology, and examine the internal processes that led to this work being programmed at all. Still others are somewhat dismayed that everyone is interpreting the title so literally when it is so clearly conceptual! They also note that neither the supporters nor the critics have seen the show and that as a result we find ourselves responding to the response without having had a chance to encounter the work itself. For my part, I feel bemused, even benumbed. I have seen this show before.

Perhaps one reason for my fatigue is that contemporary public life in Australia presents endless “scenes of appalling human degradation.” Over the past five years, I have witnessed 12 asylum seekers die in the country’s offshore immigration detention centres, taking the death toll of Operation Sovereign Borders to 73 and the number of border-related deaths in the 21st century to 2,015 (Doherty, Evershed, and Ball 2018; Monash 2018). I have witnessed prison officers assaulting Aboriginal children in their care: grabbing their throats; kneeing their stomachs; throwing them against walls; knocking them to the ground; hurling fruit at them; forcing them to strip naked; tear-gassing them; and in one infamous case hooding a 17-year-old boy and shackling him to a chair (ABC 2016).

Of course, public life is not solely national. So, alongside Australia’s scenes of appalling human degradation, I have witnessed Erdogan in Turkey, Orbán in Hungary, Putin in Russia, Netanyahu in Israel, Trump in the United States, and so on. The strong men are on the march. I have witnessed the bombing of Syria and the drowning of its toddlers. And I have witnessed the world’s indifference to most of it. Could the theatre be more degrading than any of this? Even if it could, why would we want it to be so? Why would we want theatre to participate in this economy of horror and humiliation? Yet having rehearsed this litany of atrocities, I realise that I am no longer numb. Instead I am tingling, as my flesh and conscience slowly come back to life, pushing through the pins and needles. What was I thinking when I started writing this gloss? Who is that woman in the first paragraph, so jaded and bored? Even when I have seen a show, I have not really seen it. And there is always more to see. I start reading.

Relief floods over me. It’s written by a woman; it features a woman. Perhaps this will not be so bad. Perhaps there will be a feminist twist. Perhaps the play will contemplate the impossibility of such a twist. I read on. The woman on stage is wearing “flat shoes” and is “very neatly dressed”. She could be me! Or perhaps not: she is sporting trousers and I hardly ever wear those. Enter a man, and then exit. Enter another man, and then exit again. Enter all the men – every male protagonist you have ever seen strut and fret his hour upon the stage – and they do not exit. Here come the balding and the bearded (hint, they are often one and the same). Here comes the patriarch and his son. Here comes the heir apparent and his bitter brother. Here comes the romantic suitor and his less handsome sidekick. Here comes the beggar and the mad king, the jester and the wise boy, the child prodigy and the enfant terrible. Here comes the young man on the make and the old man on the prowl. Here comes the charmer and the bully (hint, they are often one and the same). Here comes the working-class man newly redundant and the middle-class manager who made him so. Here comes the draft dodger and the war veteran, the jock and the nerd, the surprise success and the one who was always most likely. Here comes the crusader, the conviction politician, the conniving advisor, the bagman, the murderer, the one who had an affair, the alcoholic, the recovered addict, the geezer, the good bloke, and his best mate. Here comes the artist and the abuser (hint, they are often one and the same). Suddenly, I am in the mood for degradation. Let the appalling abuse begin.

But wait, a mistake has been made. Oh no. Oh no, oh no, oh no, oh no. Doesn’t this woman know that she can’t afford a mistake? She must work twice as hard for half the opportunities; there will be no second chances. Will the men laugh at her mistake? Inevitably. Will one of them help? Condescendingly. It’s okay. She can handle it. Look, she is talking now. Oh, she speaks French. Sigh. Of course she does. That explains why she’s described as “very elegant.” For the Anglophone woman, the French WomanTM seems designed precisely to humiliate her, since French Women Don’t Get Fat; French Children Don’t Throw Food; French Women Don’t Get Facelifts; French Women’s Secrets to Feeling Beautiful Every Day; French Women’s Secrets for Ageing with Style and Grace; How Those Chic French Women Eat All That Rich Food and Still Stay Slim; A Woman’s Guide to Finding Her Inner French Girl; French Women Don’t Sleep Alone; What French Women Know: About Love, Sex and Other Matters of the Heart (Hyde 2014).

This current French Woman of the Theatre reminds me of another—Hélène Cixous. I recall the line:

Nous vivons devant le rideau de papier, et même souvent en tant que rideau. Mais ce qui nous importe, ce qui nous blesse, ce qui nous fait sentir que nous sommes les personnages d‘une aventure immense, c‘est ce qui se passe derrière le rideau. Et derrière le rideau il y a la scène nue. (Cixous 1987)

(We live before the paper curtain, and often as curtains. But what is important to us, what wounds us, what makes us feel we are the characters in an immense adventure, is what comes to pass behind the curtain. And behind the curtain there is the naked stage.) (Cixous 1994, 152)[1]

Please, as if French women have paper curtains! Surely, French Women Decorate in Organic Linens? In any case, the pulling of the curtain here makes me feel like a fool. Of course the scenes of degradation are going to happen offstage or, more accurately, onstage but out of view. It’s the oldest theatrical trick in the book. It predates the book. The Ancient Greeks knew that our imaginations would have those men doing things far worse than the theatre could ever stage.

Yet the spectacle of “rotat[ing] two concentric squares of chairs” suggests that theatre’s degradation may be rather more banal. Yes, it is degrading because it stages suicides, infanticides, matricides, patricides, blindings, beatings, rapes, and violations. Yes, it is degrading because it renders its artists impoverished and precarious, stranded mid-career with no savings or health insurance and few prospects. Beyond that, though, theatre degrades as a computer does: slowing down, glitching, getting caught in strange interminable loops. Its users download upgrades only to find that the software and hardware are no longer compatible. The cursor blinks, the hourglass drains, the pinwheel spins, the blue screen of death appears and becomes a black mirror. Once theatre was the original black mirror, offering dark reflections of ourselves interspersed with backlit scenes from other worlds. Now I am not so sure.

Theatre has been, depending on who you read, a mirror, a window, a hammer, a haven, a release valve, a rehearsal for the revolution to come, a redressive ritual for the wrongs that were done, and an alternative archive for precious cultural knowledge. To borrow from Cixous again:

[L]e Théâtre c‘est le lieu du Crime. Oui le lieu du Crime, le lieu de l‘horreur, aussi le lieu du Pardon. … Pourquoi aimons–nous si immédiatement, si éternellement certaines œuvres de théâtre ou d‘opéra ? Parce qu‘en nous montrant nos crimes au Théâtre, devant témoins, elles nous accusent et en même temps elles nous pardonnent. (Cixous 1987)

([T]he Theater is the place of Crime. Yes, the place of Crime, the place of horror, also the place of Forgiveness. … Why do we love so immediately, so eternally, certain works of theater or opera? Because by showing us our crimes in the Theater, before witnesses, they accuse us and at the same time they forgive us.) (Cixous 1994, 154)[2]

No wonder theatre is having a meltdown! The system cannot help but overload, crashing under the weight of hope and expectation. Theatre, you have too many tabs open! Now there is an internal fatal error and as a result kernel panic. The operating system cannot safely recover without major data loss. The result is man-beetles rearranging chairs and a woman drawing a curtain across the stage and saying:

Je suis désolée mais vous devez partir.

(I’m sorry but you need to leave.)

In this way, the fourth wall is breached but a fifth wall is erected. The strong men would be proud.

Works Cited

Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). 2016. “Dylan Voller: Timeline of Teenager’s Mistreatment in NT Youth Detention.” ABC. July 27, 2016. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-07-26/timeline-of-vollers-mistreatment-in-detention-centres/7661788

Cixous, Hélène. 1987. “Le lieu du Crime, le lieu du Pardon”, L’Indiade ou l’Inde de leurs rêves, et quelques écrits sur le théâtre. Paris: Théâtre du Soleil, 1987, pp. 253-259. Reproduced: “Le lieu du crime, le lieu du pardon,” Théâtre du Soleil, https://www.theatre-du-soleil.fr/sp/a-lire/le-lieu-du-crime-le-lieu-du-pardon-4018

Cixous, Hélène. 1994. “The Place of Crime, the Place of Forgiveness.” Translated by Catherine MacGillivray. In The Hélène Cixous Reader, edited by Susan Sellers, 149–56. London: Routledge.

Cixous, Hélène. 1995. “The Place of Crime, the Place of Forgiveness.” Translated by Eric Prenowitz. In Twentieth Century Theatre: A Sourcebook, edited by Richard Drain, 340–44. London: Routledge.

Doherty, Ben, Nick Evershed, and Andy Ball. 2018. “Deaths in Offshore Detention: The Faces of the People Who Have Died in Australia’s Care.” Guardian, June 20, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/ng-interactive/2018/jun/20/deaths-in-offshore-detention-the-faces-of-the-people-who-have-died-in-australias-care

Hyde, Marina. 2014. “French Women Don’t Get Fat – Or Live in Actual France.” Guardian, 17 January 17, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jan/17/french-women-cliche-francois-hollande-stereotype-the-french

Instagram. 2018. “Terms of Use.” Last modified November 1, 2017. https://help.instagram.com/1188470931252371

Monash University. 2018. “Australian Border Deaths Database.” Last modified June 15, 2018. https://arts.monash.edu/social-sciences/border-crossing-observatory/australian-border-deaths-database/

Notes

[1] Catherine MacGillivray’s translation. Eric Prenowitz translates it as: “We live before the curtain of paper, and often even as the curtain. But what matters to us, what wounds us, what makes us feel we are the characters of an immense adventure, is what happens behind the curtain. And behind the curtain there is the naked stage” (Cixous 1995, 341).

[2] Prenowitz has it: “[T]heater is the place of Crime. Yes, the place of Crime, the place of horror, also the place of Pardon. … Why do we love certain works of theatre or opera so immediately, so eternally? Because by showing us our crimes at the Theatre, before witnesses, they accuse us and at the same time they pardon us.” (Cixous 1995, 342–43).

About the Author

Caroline Wake is a writer, researcher and teacher. She is Senior Lecturer in Theatre and Performance at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. She researches the politics of performance, with interests in migration and documentation. She is Editor of Performance Paradigm, Associate Editor of Performance Research, Guest Editor – with Emma Cox – of a special issue on “Envisioning Asylum / Engendering Crisis” for Research in Drama Education (2018), and an Editorial Board Member of Imagined Theatres. She is also editor, with Bryoni Trezise, of Visions and Revisions: Performance, Memory, Trauma (Museum Tusculanum Press, 2013) and author of articles in International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media, Theatre Research International, New Theatre Quarterly, and Modern Drama, among others. Outside the university, Caroline serves as a Board Member for Performance Studies international as well as PACT Centre for Emerging Artists (Sydney). She is also a long-time theatre reviewer, having worked as a reviewer and online producer for RealTime arts magazine for over a decade. She now reviews for The Conversation.

-

this is a list of edits from previous shows

in their absence other things were possible

some of them hurt

you may perform them as you like

but the instructions should be carried out to the letter or my agent capital a will jam you up capital

j a m

sorry…too aggressive

sorry also for apologising

sorry

not sorry

alternatively please feel free to ignore these instructions but only if you have a better idea and by better I mean better and not just an idea that you thought of that isn’t actually better but just happens to be yours

I’m mainly interested in the gaps

About the Author

1. a dialogue for one

– Every word I’ve ever said has been inked by a man with a silly hat.

is not said whilst wearing a hat, but we should have seen a hat previously

About the Author

2. audience

As if in a library

sh

sshh

sssshhhh

sh

sh

sh

sh

sh

sh

sh

sh

sssshhhhhhhsssshhhhhhssshhhsssshhhhhhhhhhhhh…..

sh

sh

sh

shsh

ssssssssshhhhhhhhhhhh

sh

About the Author

3. interruptions for 4 players

- What have you to say about a certain tree which is near to your village?

- Not far from Domremy there is a tree that they call ‘The Ladies’ Tree ‘-

- I’m sorry is this the only name for the tree?

- No, no it’s not the only name for the/ tree

- What are the other names for the tree?

- If you just/ let me finish

- Don’t be hostile

- I’m not…. I’m just saying that… if you let/ me finish

- Just say the name/ of the tree

- The name /of the tree is

- Don’t interrupt

- I wasn’t interrupting/, I was just trying to tell you the name of the tree

- You were interrupting. Why /are you being so rude?

- I wasn’t/ interrupting I was trying to tell you the name of the tree

- You were /interrupting.

- I’m just

- Look you’re doing it again!

- I

- Stop

- I

- Stop

- I

- Stop

1.What is the name of the tree?

2.The tree is sometimes called The Ladies Tree and /others call it

- You’ve already said, you said that already

- I know I have

- Then why say it again?

- I just hadn’t finished

- Well…..go ahead

- ……The tree is also called The

- Sorry could you repeat that last bit

- Point of order

- What

- Could you repeat the last sentence

- The tree is also called The….

- Thank you

- Sorry. Please continue.

- Yes the tree is called the Ladies Tree/ and also called

- You’ve already said that

- I

- Point of order

- What?

- Would the minister stop interrupting the witness

- I haven’t been interrupting/ the witness

- Don’t argue. You have/ several times interrupted the witness and I’m asking you to stop. See it’s happening now, point in case. Minister. Minster. Minister. Minister. MinisterMinisterMinisterMinisterMinister

- I have not been interrupting the witness I have been pursing a line of questioning, she is being hostile. All I want to know is the other name of the tree. What is the name of the tree? The tree. The tree. treetreetreetreetreetreetree

- (very quickly) The tree is called the Ladies Tree/ and also called the

- That was unintelligible

- Sorry.

- That was unintelligible please repeat that last sentence

- Case in point

- Point of order

Please repeat that last sentence

- Fairy

- I’m sorry

- Fairy Tree

About the Author

4. something durational

Is it boring?

Who cares, at least boring is something

Boring can be interesting

Maybe boring isn’t interesting

Maybe that’s interesting

No

About the Author

5. to be performed as a sexual act

the production should look expensive

the performer should be made to feel very powerful

the audience should feel turned on

You are an adonis

You look striking

You are an adonis

You are an adonis

You are an adonis

Can you see me?

How do I look?

Your. beauty. has. no. limits.

Sublime

Stay still tea gan

Your. beauty. has. no. limits.

Your beauty has no limits.

you are on the precipice of greatness

you are on the precipice of greatness

you are on the precipice of great. ness.

Art.

Your life is a work of art.

Your life is a work of art.

Your life is a work of art.

Your life is a work of art.

Raw

Meat

Do you like fine dining

So you want to enjoy your life

You would like. to . enjoy. your life.

Yes

Develop for a taste for the exotic.

Wagu

Kipling

We all want what you

5 year old grain fed tasmanian bred beast.

5 year old grain fed tasmanian bred beast.

20 year old cop de ora enge enough for the table.

Service with a smile.

Live jazz

Live jazz

Live jazz

Live jazz

Live jazz

Live jazz

Live jazz

Live jazz

Live jazz

Velour curtains

And real candelabra chandeliers

Enough for the table

Quail brain

A tailor made tuxedo

She should sing your song

You want french cologne

You want tibetian silk boxer shorts

Enough for the table

Enough for the table

Slow roasted kipler dill trim skinny dipped pasta on the side Slow roasted kipler dill trim skinny dipped pasta on the side Slow roasted kipler dill trim skinny dipped pasta on the side Slow roasted kipler dill trim skinny dipped pasta on the side

You want sea stars

Enenemies

Sting Ray

Tiger Shark

Whale

Whale

Whale

whale

Killer

Whale

You want a galaxy of fish

A bio system

A bio system

a food chain

a living living food chain in my big big

Big big aquarium

Live jazz

Live jazz

Live jazz

Live jazz

Live jazz

Live jazz

Live jazz

Live jazz

Live jazz

She’s very good

Very talented

Even the little fish are dancing

Yeah

Cabaret

Yeah

The fish the fish are singing and dancing

Slow roasted duck roasted angel hair pasta skinny pasta

It had to be you

It had to be you

I wandered around

Finally found

Somebody who

Could give me a thrill

Could pickle my dill

It had to be you

Wonderful you

Wonderful you

It had to be………..

suckling

sucked

trimmed

tort

terrific

six pack

iron

fisted

you

It had to be………..

suckling

sucked

trimmed

tort

terrific

six pack

iron

fisted

you

It had to be………..

suckling

sucked

trimmed

tort

terrific

six pack

iron

fisted

you

It had to be………..

suckling

sucked

trimmed

tort

terrific

six pack

iron

fisted

you

It had to be………..

suckling

sucked

trimmed

tort

terrific

six pack

iron

fisted

you

you. can. do. anything.

You can be that guy!

That. guy.

That. guy.

You can be that guy!

Your. beauty. has. no. limits.

You. are. an. adonis.

What’s adonis?

You have god like super natural beauty

You can part the sea with those looks

I’m not kidding

You could look at the sea and it would split in two

You should have fish

You should have gold fish

You should have an aquarium.

You can have the great barrier reef

Where do you buy that?

Reef

I want a piece

I want a thousand year old piece

Some exotic little fish

I want something that changes colour

Really little fish

I want really glory fish

I want the ones that hide in the sand

I want the ones with blow holes

I want flippers

I want gills

There you are

As long as those eyes are soft

You can have anything you want

My friend

As long as that skin is line free

You can have anything you want

Any time any where

Aquarium

Bubbles

Ten Mill Glass

Bullet Proof Glass

Wall to wall

En suite

ten Nemos

twenty Nemos

Yeah

yeah

Could I have 30 Nemos

You can have 40

You are an adonis

Get closer

You are perfect

You have a tight arse

You have great abs

You are so natural

you are so carefree

You are so so deep

Are you free tonight?

Are you free tonight?

FFFF I’ll do the thinking

FFFF I’ll do the thinking just be

FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF

Do you like ormolu

It is so right now

effortless beauty

If you were FFFFFFFFucking care free

Care free cars

Do you like them?

Blue Liquid BMW

Personalised plates

Wet

Wet

Wet

Wet

Ormolu

Ormolu

Mazarati

FFFFFF

FFFF

Blue

Steele

Bon sai

Re bock

Pump

F

F

F

Japan

F

F

You do

FF

You like japanese food

Hey there’s that carefree natural beautiful young man

It’s free mother fuckers

Get a fish

Get a gold fish

Get an aquarium

Sea eneminines fucking

About the Author

-

About the Author

About the Author

-

An imagined cast – a very tall, shiny-domed, environmentalist, ex-politician, musician, male

An imagined acknowledgement of country – I’d like to thank the Plairhekehillerplue people from Emu Bay NW Tasmania, for their ecological stewardship, and their diplomatic governance for over 2000 generations, and apologise for my role in the ongoing disruption of last 10 generations. I also ask for assistance with the infancy of our understanding of country – on which our species survival depends.

An imagined over used word – the disruption of the common usage of the word disruption.

An imagined context – language as insidious genocide weaponry

An imagined opening and closing scene – Portrait of another disruption, circa 1981.

You are staying at the Menai Hotel South Burnie, NW Coast, Tasmania, circa ‘81

Staring from a smudged 5th floor window,

Morning after the gig the night before,

Picture the sticky BOAGS soaked carpet of that Menai band room, Mr X playing support,

A crowd of flannies and mullets, thongs and crutch-huggin-stubbies, middle of winter.

Next morning, awake, looking out over South Burnie’s, lichen-tinged, asbestos rooftops,

Pure povo,

Pulp ‘n Paper chimney stacks belching that addictive smell of slightly off sweet meats,

An Easterly whips up the Bass Strait surf,

A bank of chlorine foam the colour of mucus piped from pulp to surf, blow back,

Piling up off the beach and across the highway in front of the mill,

Families whoop in delight driving through, car disappearing into mucus,

Kids squealing, belt free in the back of the rusty commodore.

5th floor Menai, looking through your misty window breath, you see a couple of surfers,

Out riding steep ashen faced dumpers, clawing up out of shallows,

Waves browned by sunken woodchips,

Dumpers slap the grey beach sands,

Washing up, ancient forest chips and a few tenacious spiky blowies, impervious to poisons

Slapping the sands where three skanky kids play, near the storm water drain.

Rub that foggy Menai window, stooping tall man, rub with your jumper sleeve,

There see it, across the road,

A picket line outside the rusty Pulp and Paper mill gates,

Look closer, who is that, a young Brian Green – an also-ran-Labour-opposition-leader,

In brown vinyl jacket, with collars wide enough to trigger op-shop hipster ejaculate,

Barking slogans handed down from Chiffley, to high-viz acolytes, cupping cup-a-soups.

And here you are, too tall and hungover – haven’t touched a drop –

From passive smoking under the Parcans on that squat Menai stage, ears ringing,

Trying to build a career in this god forsaken place,

You, with your Sydney Northern Beaches birthright born of the fortunate people,

Where every day the surf is caressed by a warm, sea breeze Zephyrs,

Here you, in the poorest electorate, in the poorest State – the Menai, cunt of a place,

With a one bar radiator and a guitar case full of broken dreams,

Fallen from pop-grace like only a silent, private Christian can fall,

And you can’t believe what’s outside your window…

So you write these words… in the tradition of the great 18th century Hymn-sters

The social media of its day… a perfect evangelis song of horror and redemption (who cares if it doesn’t scan. It’s a cry from the heart, from within the devil’s lair, the Menai…)

Brought up in a world of changes

Part time cleaner in a holiday flat

Stare out to sea at the ships at night

No anaesthesia, I’m gonna work on it day to day

No zephyr no light relief it seemsBut maybe it’s a dream

This is my home

This is my sea

Don’t paint it with the future, of factories

I want to stay, I feel okay

There’s nothing else as perfect

I’ll have my wayBrought up in a world of changes

Two children in the harbour

They play their game storm-water drain

Write their contract in the sand, it’ll be gray for lifeBut you can’t stop the sun

From shining on and on and getting you there

Tide forever beckons you to leave

But something holds you back

It’s not the promise of the swell or a girl

Just a hope that someday someway it’ll be okay

So you stop and sayThis is my home

This is my sea

Don’t paint it with the future of factories

This is my life

this is my right

I’ll make it what I want to

I’ll stay and I’ll fight“Burnie” – Midnight Oil (1981)

The City of Burnie the love child of disruption long before a multi-millionaire Prime Minister, started bandying that word around with the help of his agile speechwriters.

‘Disruption’ callously and implicitly says, “come on people, it’s your fault if you didn’t see change coming.” So what if this ‘disruption’ means your kids won’t ever be able to afford to own a home; it’s your fault… it’s not this creeping rot of silent inequality, this global shift that means that apparently 17 people control 80% of the world’s wealth – according to Christine Legarde – it is just disruption, nobody is pulling the policy levers to make it happen; wake up people it’s your fault if you didn’t see it… like I did, when I had my exciting start up called ozemail… I saw that daggy name had a shelf-life… sold it at just the right time, with a couple of larrikin lads from Sydney’s Private schools… alright future white-collar crims, but don’t split hairs… politics of envy, politics of envy, people… wake up…

It’s your fault if the Paper Mill closes – with minimal global change-management – and you take a package, and your son will never have that apprenticeship you and the missus were hoping for, and your drinking spikes with self-medicated-depression, and your wife leaves you with self-medicating-adultery, and you get a bit punchy with the bouncer at the Menai, and get locked up a night or two, and your boy doesn’t wanna come home every night, and you’re a man, and you don’t ask for help, and you worry about him, and you’re a man and you don’t say anything to him, but you look… you give him that look… and he’s almost a man and he’s supposed to understand… and you don’t know it, but he’s trading blow jobs for a six pack of BOAGS in the council car park… wake up buddy, it’s just a disruption.

And if Brian Green – the wide collar worker – had made it to Federal Politics, he could’ve given the rebuttal: could the politics of disruption be just the shadow of the politics of envy. Could it be an insidious way of saying to the less fortunate masses, “you have nothing to be envious of… you just didn’t see it coming you, loser… this stagnation of wages growth… come on, a bit of agility people please…” Brought up in a world of changes… Fuck the theatre… The toothless theatre, playing to subscribers and status junky festival audiences. Let’s have a song.

Brought up in a world of changes…

This is my life

this is my right

I’ll make it what I want to

I’ll stay and I’ll fightThis is my home

This is my seaI’m a playwright by trade, and like Wainwrights and Shipwrights, in this modern world Playwrights are pretty useless. It is a dying art. Seriously disrupted.

Where I live on the NW Coast… is the home of the Tommeginna people. So actually…

This is their home,

This is their sea.

This is my life

This is my right

I’ll make it what I want to

I’ll stay and I’ll fightAnd fight they did – even further up the coast at Cape Grim (Pennemuker country) – the warrior, Tunneminawaite fought hard, when his sisters and aunties were taken for the sex trade to Kangaroo island – servicing the whaling industry. He fought, he murdered and he was the last man publically hung in Australia – in Melbourne, just down the road from Flinders Street station.

Was this just a kind of disruption? Or did this have another more appropriate name – genoruption perhaps? Have to be careful of the insidious violence of word weaponry.

Listen careful when they harnessed against their will. “Cleansing” is a beautiful word (West Germanic – Klainson, via Old English Claensian – purity, chastity, justifying)

But put “Cleansing” beside the word “Ethnic”…

This is my life

This is my right…

Disruption – from the Latin Disrupto – to split apart, break into pieces, to shatter.

Fuck our insipid toothless theatre. I’ll never write again. Can’t even imagine it.

Scott Rankin is the Creative Director of Big hART, which began 25 years ago in Burnie as a response to the closure of the Pulp Mill.

(with thanks to Midnight Oil)

About the Author

Disrupt – Drastically alter or destroy the structure of…. In this case, theatre. By political apathy, or evolution, time, fashion, apathy, market forces. Like the well-made play of another era, traditional skills of the playwright are out of fashion, no longer needed, set aside. Disrupted. Drastically altered, perhaps even structurally destroyed. I don’t care. Playwriting and theatre-making aren’t the same thing. The playwriting isn’t important. The theatre-making is.

Burnie, on the North West coast of Tasmania was once called Emu Bay. There were actual emus when the Van Diemens Land Company first came, but the emus are extinct now, the cultures of original inhabitants of the land displaced by stern Christianity. The 20th century was about factories, the paper mill, toxic chemical spills, layoffs, financial and social disadvantage. Now the port, the woodchip exports and former senator Jacqui Lambie, Burnie’s beloved daughter (heart-on-sleeve working class political aspirant, xenophobe, bachelorette, battler), live cheek by jowl with academics, greenies, and now ubiquitous bearded baristas, surrounded by a wild landscape of indescribable magnificence.

I am new to the neighbourhood. I’m here to design a festival for this community, and theatre will be at this festival’s heart. My gut tells me that in a place like this, theatre can still matter. Sitting together and telling stories matters. If our theatre is insipid and toothless it’s our fault, and that matters too. Responding to the insidious violence of word weaponry in the world outside is the beautiful violence of word weaponry in theatre.

Words matter. Language matters. Language and words aren’t the same thing. Language is a contested thing for the Traditional Owners of Tasmania’s North West. We will create, choose, design for our festival a theatre language with whatever it takes to connect people. Whatever it takes to welcome, to let conversation flow inside and outside the performance space, to share ideas and feelings, to share time, and breath, and human experience. The language we create for our audiences will peel back our equipoise, show our raw flesh, expose our terrible secrets, celebrate our best selves and the epic in the banal, make visible our nocturnal ramblings, stir us to irrational fury, move us to tears of joy and wound the heart.

It won’t be formal. It won’t be expensive. It won’t be grand. Our festival will be Burnie itself, a meeting place for real people and great art experiences amid local streets, beaches, industrial precincts, workplaces, suburbs and civic spaces. Our theatre languages – not one, but many – will reflect the myriad visual, physical, social, musical and storytelling lives of our place and time, in the local vernaculars.

This is personal, it’s now my neighbourhood too.

There won’t be a playwright anywhere near it. But there will be theatre, and theatre makers everywhere.

Lindy Hume is the artistic director of Ten Days on the Island 2019 and 2021

4 July 2018

About the Author

-

To touch, see, perceive, this is the strength of art, which looks at the things outside with wonder. Art is continuous astonishment.

-Viktor Shklovsky

I would like to stage Uncle Vanya in the crumbling house in Krivina – a village near the Danube – where my father spent his childhood and I spent the summers of my childhood. I would like the house to be un-crumbled, to undo the damage done by an earthquake, time, distance and neglect, and to place the performance and the audience in that house. Krivina is where I learned about land, and – it is near two rivers – about water. My father used to go fishing in the river, and I with him. The surrounding fields were covered in wheat, sunflowers, watermelons, corn, strawberries. The Danube and Yantra were full of fish. It was quiet and everyone knew everyone and the streets were not paved over. It sounds like another time – and it was. I think Krivina, without knowing it, is where I really learned about play, imagination, and therefore, about theatre.

In Krivina summers we – a crowd of children – used to play strajari i apashi, which loosely translates as “cops and robbers.” We split into teams. The strajari (cops) gave the apashi time to get away, the apashi ran and the strajari chased, and when caught there were rhymes and rituals, then more chasing. We ran around the whole village – or at least it felt like that – we ran in neighbouring streets. We ran barefoot. We climbed fences. We picked fruit off trees. The adventure was total and euphoric. It was unbounded joy. We were allowed complete freedom into the evening. And then, in the evening, the only sounds you could hear were donkeys, occasional dogs barking, a cart going home, people’s voices. The air was sweet and quiet. Nature surrounded all.

Seeing the world through the eyes of the game, being at once in the imaginary world and in the real world with a new sense of wonder and noticing, alive and excited: that is what I long for in theatre. This awakened seeing, in relation, is reminiscent of the moment in Martin Buber’s I-Thou, when he writes about the possibility of really seeing a tree: “That living wholeness […] of the tree […] discloses itself to the glance of one who says Thou […] something lights up and approaches us from the course of being” (Buber 2013: 89).

Johan Huizinga writes about play being central to culture, being of the real world and make believe at the same time, being fun yet deeply serious (Huizinga 1955). The playing in Krivina was like that: the game spilled into the surroundings, and at the same time invoked the surroundings into the game: yards, fences, dusty streets, fruit trees, outside toilets (a new slipper fell into one once) – playing the game was entering more intensely, somehow, into the real world. Playing called the real world into our game and our game made the real world come to life fully, made it more itself, real and magical, vivid, everything mattered. Performing there would be like playing strajari i apashi – the world of the play immersed in the real surroundings. Shklovsky wrote: “Art exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony” (Shklovsky 1965:12). He asked: “what is art’s great achievement? Life. A life that can be seen, felt, lived tangibly” (Vitale 2013: 53). Can performance be this? Can it awaken me to sense in a way that matters? Not to close off from the world to enter the performance (as performer or spectator), but to enter the world more vividly, through the play? A performance that is a heightened experience, a game, within the real world?

In The Concept of Body as the Nature We Ourselves Are, Gernot Böhme writes about moments in which we are fully in life, in the body, as moments of what he calls “joyous emphasis”:

Emphasis is joyous participation in what happens of its own accord. One example is a child racing off along the beach…There are life performances that are experienced with a tendency toward intensification…Emphasis is therefore a way in which we ourselves are nature, on occasions when being-nature is experienced not as a burden but as a joy. (Bohme 2010: 236 emphasis mine)

This, I think, is akin to play, immersed in the ordinary, but with a heightened joy. As Huizinga writes, “the fun of playing, resists all analysis, all logical interpretation” (Huizinga 1955: 3). And certainly, it is akin to the experience of theatre.

I want to feel the play in that place: a lived, three-dimensional artistic event that is at once imaginary (the events of the play) and real (the place for performers and audience alike). As Tadeusz Kantor wrote, theatre that “(includes) r e a l i t y o f f i c t i o n in the r e a l i t y of life” (Kantor 1993: 36).

I want to stage Uncle Vanya in Krivina because that’s where it all started for me, the connection to land. Chekhov’s play is about trees, land, happiness, time, and wasting time. In it he suggests the anxiety of extinction, of things passing irretrievably. It is also a play about change, taking responsibility for change. To me the play says: “If change is needed, do something. Change something.” I also want to stage it there to remember that land and water are precious, but we live in a way that seems to forget this. In Krivina the seasons and the food from the land were present in a felt relationship, close, proximal. We walked from the river, rode donkey carts, picked fruit with our hands, crushed grapes with our feet to make wine. There was little plastic. In the evening songs were sung. We washed in tubs, in water warmed in the sun. The soil was fertile and the mulberries black, sweet and huge. But most people left. It is now a village of few, mostly old, people. To perform there will be to “make whole what has been smashed” (Benjamin 1968), to perform in both the past and the present, and to connect art and land.

We have performed it now in Australia in four places (Avoca, Eganstown, Steiglitz, Bundanon). I want to now stage it in the crumbling house in Krivina to say – come to this beautiful place that is not really here anymore. Ways of life, land, water can be lost. And that has implications for the choices we make for the future.

Theatre that is part of place, but also traverses place and time, to invite people into an experience that is more fully alive.

The streets were dusty and all sounds carried in the surrounding quiet.

REFERENCES

Alexandra Berlina. Shklovsky: A Reader. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016..

Gernot Böhme, “The Concept of Body as the Nature We Ourselves Are.” The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, Vol. 24, No. 3 (2010): 224-238.

Martin Buber. I and Thou. Translated by Ronald Gregor Smith. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

Anton Chekhov. Chekhov: Five Plays. Translated by Ronald Hingley. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Anton Chekhov. Sobranie Sochineniy (Collected Works). https://az.lib.ru

Johan Huizinga. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture. Boston: The Beacon Press, 1955.

Tadeusz Kantor. A Journey Through Other Spaces: Essays and Manifestos, 1944-1990. Edited and Translated by Michal Kobialka, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Bagryana Popov. “The Uncle Vanya Project: Performance, Landscape, Time” in Art, EcoJustice, and Education: Intersecting Theories and Practices. Edited by Raisa Foster, Jussi Mäkelä, and Rebecca A. Martusewicz. New York/London: Routledge, 2018.

Viktor Shklovsky & Serena Vitale. Shklovsky: Witness to an Era. Translated by Jamie Richards. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Viktor Shklovsky. “Art as Technique” in Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays. Edited and Translated by Lee T. Lemon and Marion J. Reis. Omaha, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1965..3-24.

Walter Benjamin. “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” Illuminations:Essays and Reflections. Edited by Hannah Arendt. New York: Schocken Books, 1968.

About the Author

Bagryana Popov’s imagined performance pushes her ongoing theatre project with Chekhov’s drama to the limits of where life and theatre converge. I loved her production of Uncle Vanya for such a convergence; I viewed the first iteration in Avoca. It was performed in a house that was as near as possible to a late nineteenth-century Russian house – a historic wooden two-storey house imported from Sweden and assembled on the banks of the Avoca river under gum trees. The production started in the front yard and, slowly over two days, we moved with the characters through the house and out into the back yard. In the breaks, environmentalists gave talks – Chekhov’s Astrov had multiplied. This was a long way from the contained theatre of a Chekhov play presented over a couple of hours and yet it was the same play. Instead, the audience was living with the characters in that house.

The idea of theatre as a lived reality has become part of our twenty-first century experience as the boundaries between reality and performance come unstuck, and theatre’s imaginative foyers are reconfigured. The widespread uncertainty – “this cannot be happening” – over actual news and its faked simulacra; the horror about politicians and others who tweet rather than think their random hateful thoughts; and inactivity as the changing climate threatens the homes of the global poor. But there is something unexpectedly reassuring about how Bagryana imagines her life as theatre, perhaps because of the surprising continuity that I have found in Bulgaria where the remnants of two 8,000 year-old-houses are preserved in Stara Zagora. A type of lived theatre that globally connects Australia to Russia and Bulgaria in the nostalgic idyll of the Krivina house of Bagryana’s childhood somehow seems vividly real.

About the Author

-

It is possible to communicate with the dead.

It is possible to communicate with the dead via psychic ritual with gnomes.

Unfortunately, the practice of these rituals with gnomes that result in a clear communication with the spirit world can only be accessed on a remote farming property located on the northwestern Tasmanian coastline.

The audience will have to go there.

For centuries gnomes have been living with humans as various morphisms of plants and animals, and it is only recently they have evolved into ceramic garden objects of desire and distaste. A particular spiritually-evolved group of ceramic gnomes is currently in the possession of a farming family of long standing historic relevance to the western regions of Tasmania. The Legge-Willlkinson family of prosperous farmers dates back to the British colonisation of Tasmania in the early 1800s. The family settled near Rocky Cape, known for its caves of significant cultural and Aboriginal importance.

The family has taken enormous risk in recent years exposing their gnomes’ medium abilities. It was the year 1911 that young Jacinta Legge-Willlkinson, daughter of Alice and Jim, was discovered laying face down in a field in a condition by what is described in a forensic report held at the Bernie local courthouse as “spinning on the ground in a state of unsound persons of mind and in fits of nonsensical speech.” The report also records the whereabouts of several gnomes located in some proximity to her fitful body. Fortunately, no further reference can be found in any later reports explaining the gnomes’ presence in the field that day.