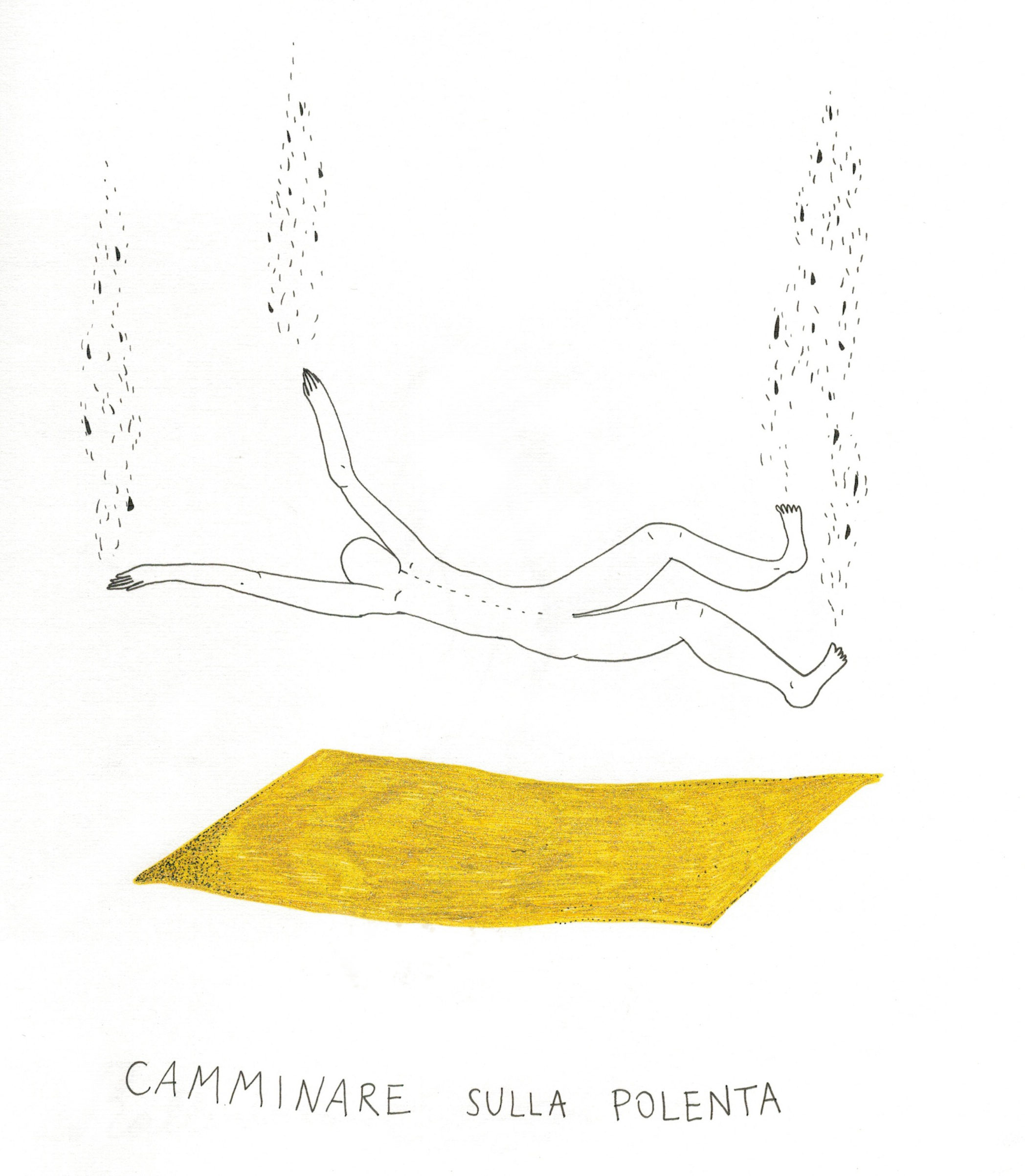

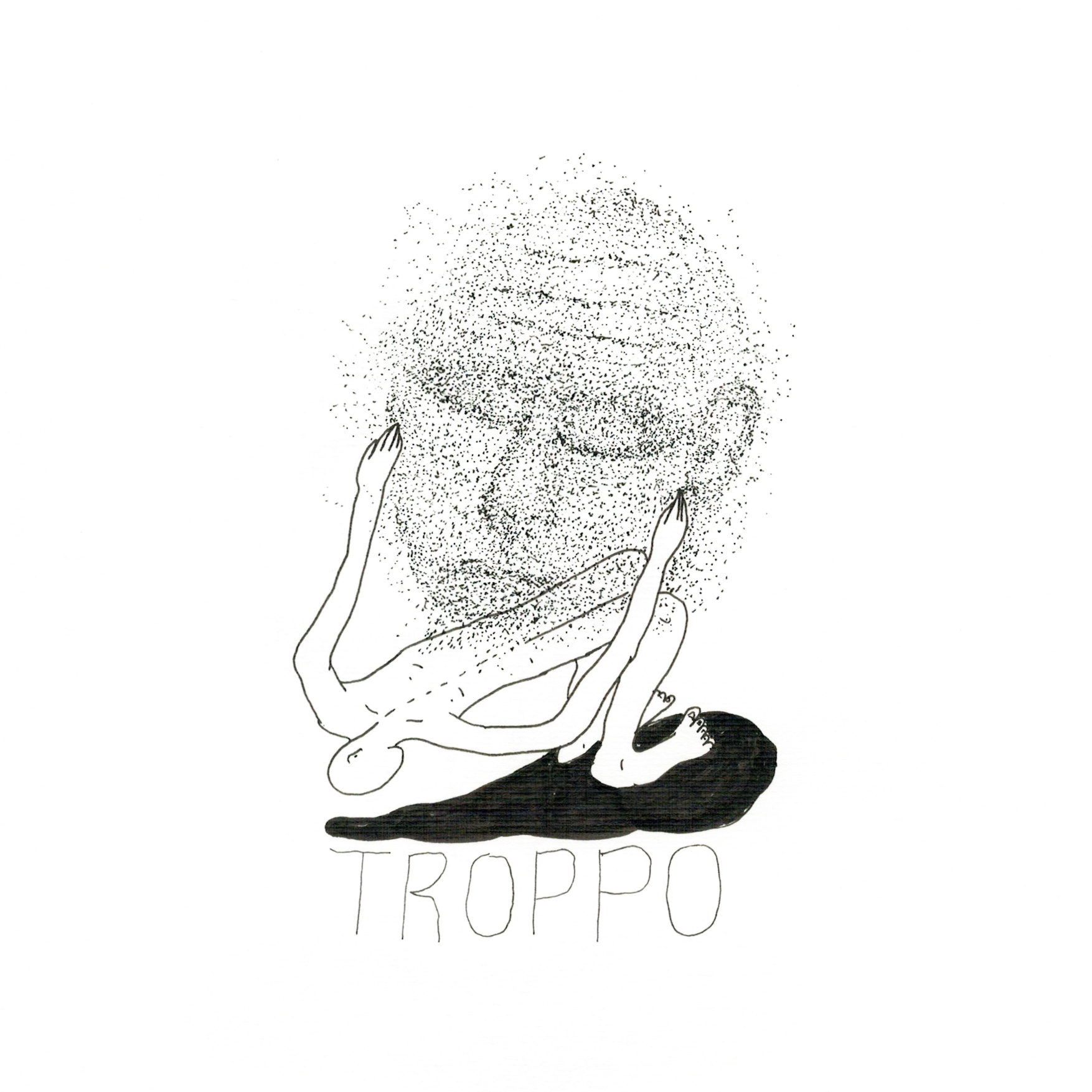

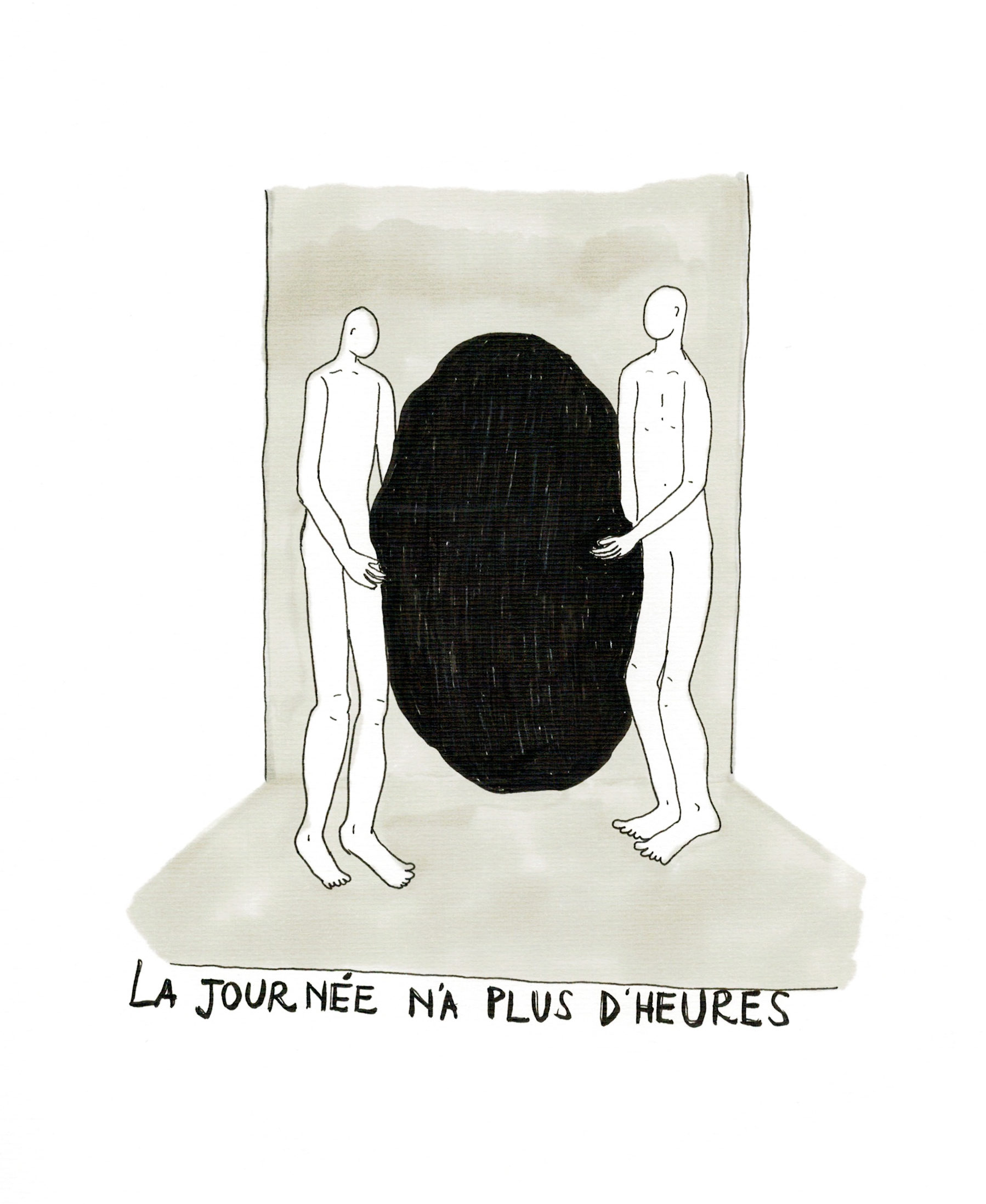

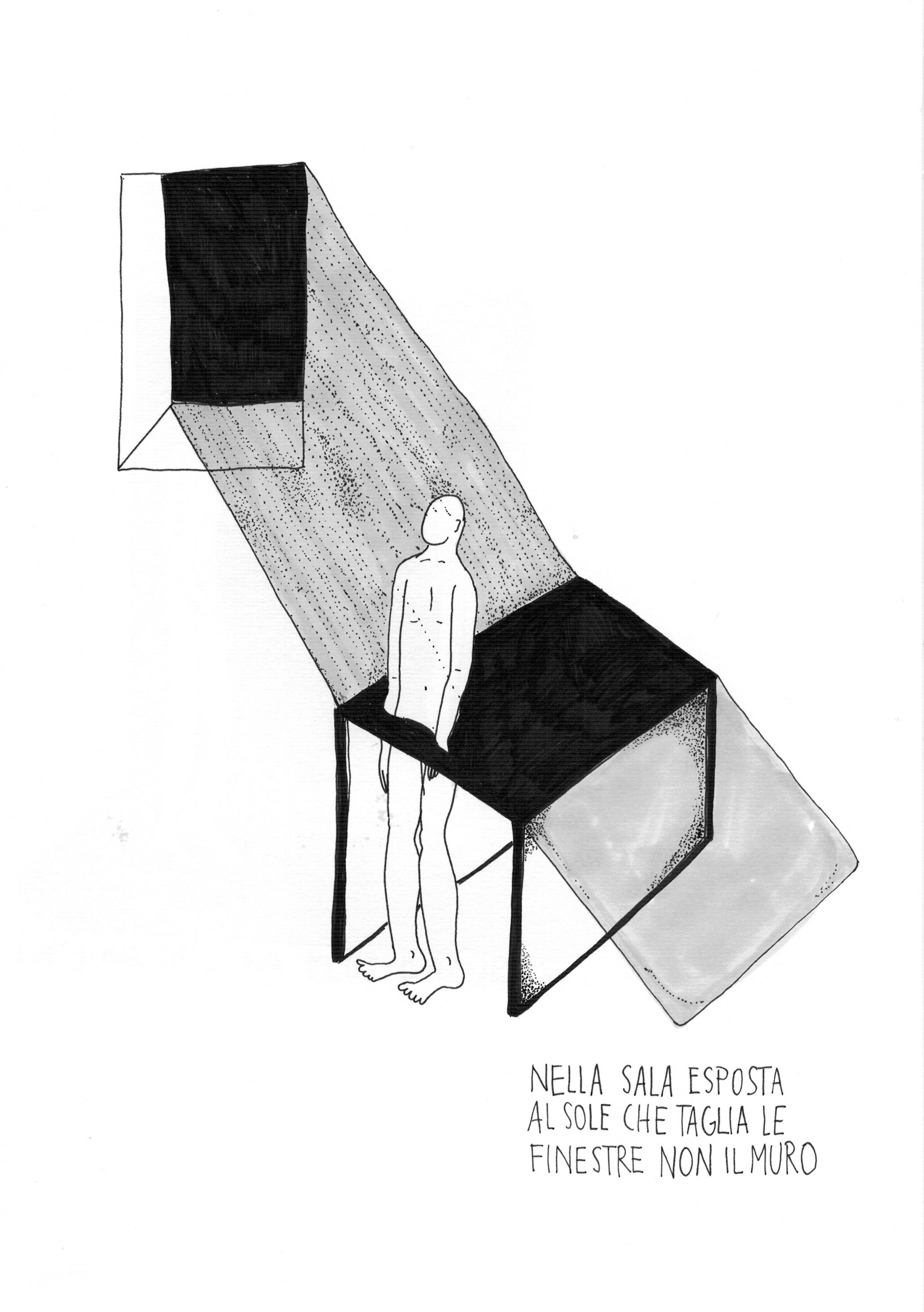

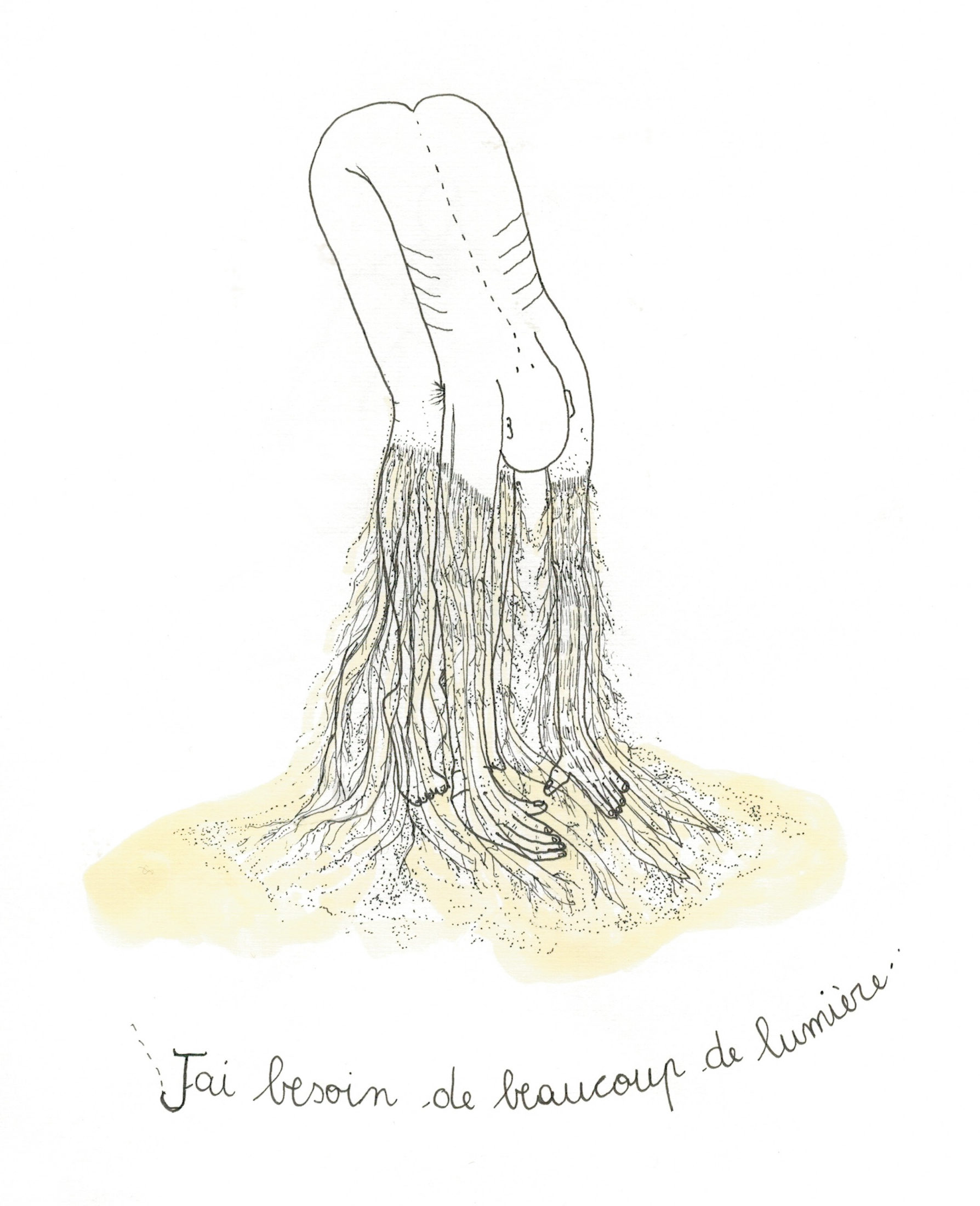

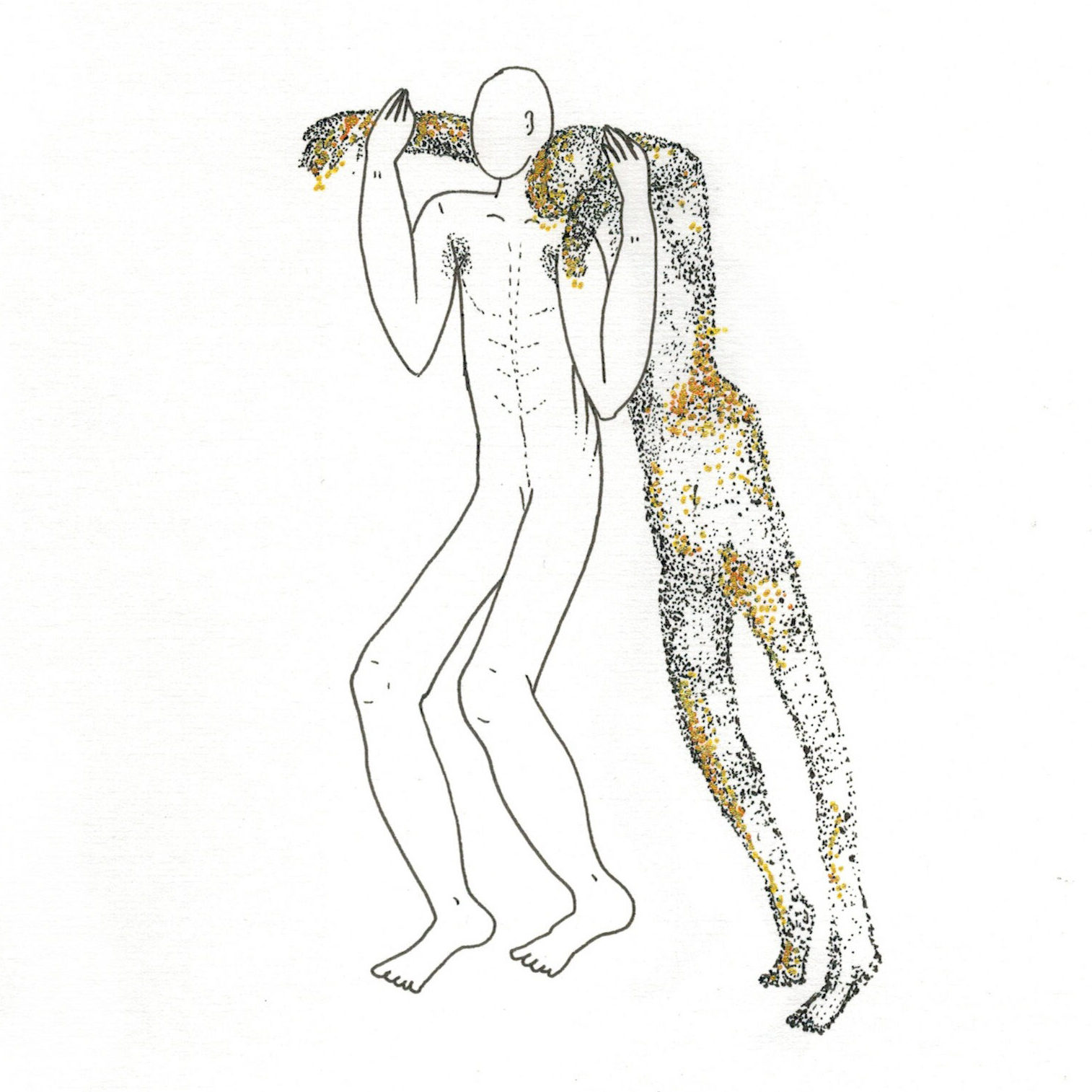

Silvia Costa’s works convey impressions that may have briefly crossed our mind, or may linger permanently inside us. These drawings seize encounters, enclosing them in a gesture that at the same time unfolds, narrates, tells a story, names “what is.” Minimalistic, they show humanoid figures without eyes or ears, and – most importantly – without sexual attributes; they stage beings on a white background, with no individual identity, gathering thoughts in short captions that line their silhouettes.

Silvia’s operation also expresses how the art of a woman, as “unexpected subject” (to quote Carla Lonzi), is not only set apart because of the feminist themes it deals with – like body, sexuality, domination, exclusion, power – but rather for the ways in which it experiments and imagines her own identity as being always traversed by other entities, as something giving and receiving, something closing and opening.

These sketches play a very serious game, putting themselves in harm’s way: with the specific practice of drawing, it is possible not only to transpose an emotion and its feeling, but also to broaden the logical possibilities of thought and of the hand that carries it. A hand also has a way of thinking of its own. With our hands we hold objects, things we can carry with us; we can hold someone else’s hand, let them guide us, or be the ones who guide. Drawing offers a way to relate that is not just visual and rational, but also haptic, meaning tactile and sentient.

Drawing possesses the capacity to express time and movement. In this regard, drawing is closer to disciplines such as dance and music than to painting or photography. While photography stops time, freezing forever an instant, drawing—such as Silvia practices—flows with time, operating with hand and pencil not just a translation but also a transduction. In other words, it brings the gesture’s kinetic nature from the register of conscious action and willed movement to the ground of a subconscious and material flow, a durational becoming. Sewing the line to the mind, and sometimes the mind to the line, it approximates what anthropologist Tim Ingold calls a suturing action.

I like looking at Silvia’s drawings from this perspective, as a creative process that isn’t the projection of an existing and fully formed idea on any kind of medium, but rather the expectancy, a dialogue between our own being and the material substance of our bodies and of surrounding objects – a process of cooperation, in all the meanings of this term. To correspond and cooperate with the world through drawing is to practice, following Ingold again, a graphic anthropology, an anthropography.

If we look at these drawings more closely, this anthropography is sometimes somber, sometimes ironic and giddy. It is a movement that simultaneously investigates encasing and opening up, hiding and revealing; it is a movement always on the boundary line of dichotomies, denied in their apparent juxtaposition.

It must be with the sound of bells,

It must be with the sound of bells,