08

Borders

In this ever-lengthening period of manufactured crisis relative to the Mexico-US border, borderS focuses on borderlands, expansively defined. Ten contributions in Spanishes, Englishes, and Spanglishes paired with ten glosses in a comparable translanguaging range, assume the form/s and shape/s of the sonic, the visual, the written… y más!

-

Ricardo Dominguez

Editors

Amy Sara Carroll

Theatres

- 1.Lázaro comienza a llorar en medio de la noche

- 2.-o / -a / -x

- 3.Un Mojado Azteca Desahogándose en el Norte

- 4.Interference and Performance Art at the Mexicali-Calexico Border

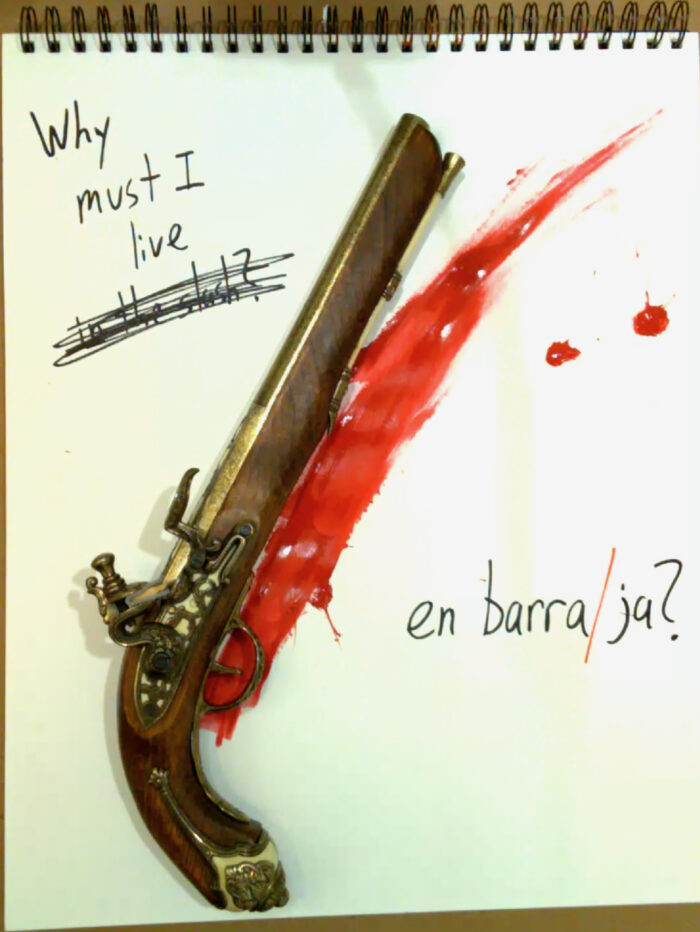

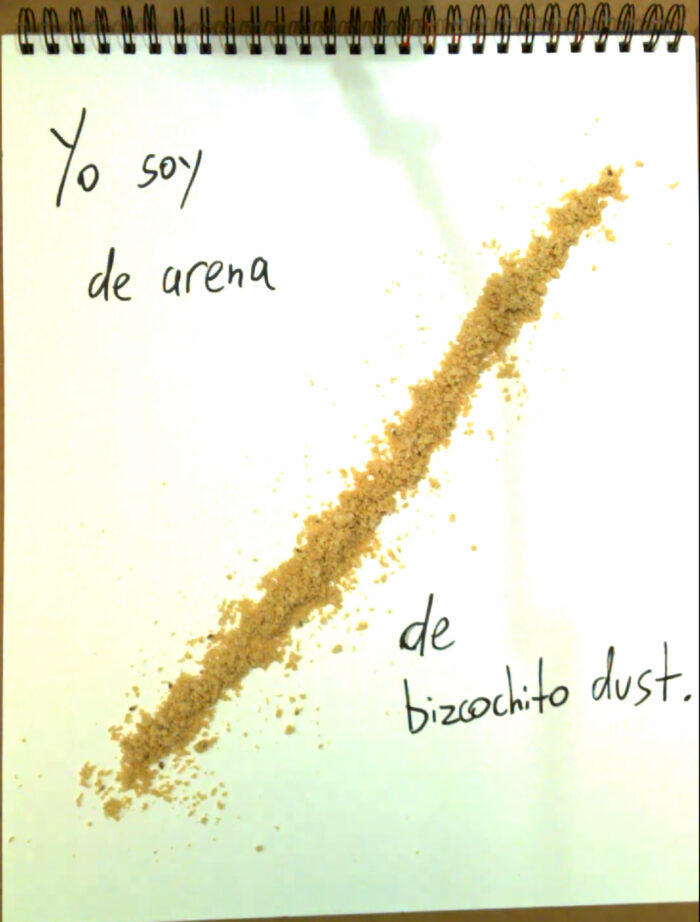

- 5.Sketches Relating to a Line

- 6.A comet enters

- 7.Four States of the Border

- 8.imagen-claraboya / imagen-vidente

- 9.[:micro borders para territorios alien or fake]

- 10.Paso del Norte

Prologue

BORDERS (Part I)

borderS, or, Imagined Theatres contra “imagined theatres”

In this ever-lengthening period of manufactured crisis relative to the Mexico-US border, “borderS” focuses on borderlands, expansively defined. Ten contributions in Spanishes, Englishes, and Spanglishes paired with ten glosses in a comparable translanguaging range, assume the form/s and shape/s of the sonic, the visual, the written… y más! Somewhere midway through the editorial process, one of us accidentally inserted into the mix a typographical error (otherwise known as the “feminist glitch”): a capitalized and italicized “S” in “borderS.” In hindsight, we recognize this “S” as generative because the other, accepting the typo at face value, ran with it as an organizing principle for the entire volume. (Alternately, we cannot forget the bold little “b” of the same fortuitous “errorism,” rounding out a critique of the “b.S.” of “order” in “borderS” per the rhetoric of enclosure and containment.)

Hear the re-alliteration of plurality: Here the S is “transfronterizomatice/x/a/o” per the neologism of Omar Pimienta and the b of IVF birthing and the S of the bending river of Rachel Price’s locative déjà vu; the S of Alaric López’s storied silence and pintura-de-acción poetics and Perry Vázquez’s surround-sound analysis replete with Sam Shepard citations ( “Texas, Our Texas”… “all hail the mighty state” re-becoming “Texas, Poor Texas”… “all failed, right-wing state”); the S and b of sacred snakes unboxing the desert in Isidro Pérez-García’s lucha libre and Daniela Lieja Quintanar’s spirited sporting captions; the S and b of Rosalía Romero’s attentions to the SSSSSS of ICE shavings and the drone of echolocation and Grant Kester’s appositive short survey of aesthetic (judgment) and the accessory apropos of the borderization built into binaries; the S-n-b of Cognate Collective’s and Susan Briante’s crónicas and cut-ups of complicity and solidarity (note, if Kamala Harris loves Venn diagrams, we applaud the “amalgamation waltz” of these contributors’ planetary kinship diagrams); the operatic S of colliding space stones in Lorena Mostajo’s and Pepe Rojo’s call-and-response meteor shower; the S and b of robyko ∞’s “Four Border States” and Brandon Som’s ekphrastic haibun enacting permutations of ecstatic transubstantiation; the S of Saúl Vargas Hernández’s meditations on a 19th century image, an obelisk’s placement or removal, marking the beginnings or endings of a Border versus Nadia Villafuerte’s return to a source, the equally provocative proposition that the obelisk was never in fact an obelisk, but a stone and ritual in concert with not only Vargas Hernández’s contribution but robyko ∞’s, Mostajo’s, and Rojo’s; the S and b of father-daughter solidarity and separation in Maribel Bello’s scripted erasures as critical embrace and distancing vis-à-vis Desirée Martín’s analysis of “irregularidad” as a “literal condition that never has the privilege of metaphor;” and finally—as in last, but not least—the S of Sebastián, the patron saint of Ciudad Juárez, reuniting with the X of a fire, a map, a train’s path, a scar… in Zazil Collins’s prose poems merging into the Soundcloud and Alaíde Ventura Medina’s paired Spanish-English aphorisms that highlight inequities in truisms normalized for the everyday.

The atomic facts of the post-1848 Mexico-US border are entangled, but inconsistent hasta la nivel nano; discursive threads; like shifting lines that live-stream disputes over water, land, sky management, bio- and necropower (“How the West was won” times “the barbaric North”), the pastoral, raised to the power of two, three… ad infinitum (a performative Matrix that assaults our matrices). Consider the sharp uptick in violence, consistent with transitional periods following Mexican Presidential elections, exacerbated by another forced transition in leadership—the July 2024 arrest of the “capo de los capos,” Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada. Electing a woman president, while historically significant, saves no one when the goal of “salvation” is from-the-jump problematic and when the highest common denominator of all political parties across the MX-US subcontinent continues to be that of corruption. Cue up AMLO’s passing-of-the-peso-and-torch as he simultaneously casts blame on the US for the latest narco-power vacuum and cedes the stage to his MORENA protégé, Claudia Sheinbaum. Reckon with his administration and coalition’s contradictory impulses (e.g., an unwavering support for the working poor, dismantling of cultural sectors, callous disregard of feminicide spikes, and funding of the unnatural disaster of the Tren Maya). Consider the 2024 US Presidential election where Democrats and Republicans alike mobilize the “imagined theatres” of “Border” with a big “B,” presupposing “reconquest” and the hyper-need to seal off un/authorized routes and ports of entry. Sit for a moment with Kamala Harris’s pick-up truck-tough home(land) security rhetoric, “If someone breaks into my home, they’re going to get shot.” Drill down on Project 2025’s fabulist propositions for and on immigration policy, authored by America First Legal, an extremist, xenophobic cabal led by white nationalist, former Trump Administration advisor, Stephen Miller—the mastermind behind the US’s latest mass deportation scheme. Project 2025 outlines a “final solution” to a fabricated problem, arguing for “big government” to bring in the National Guard, state and local police, other federal agencies like the DEA and ATF, and if necessary, the military to bunker the border. In this theater of war—a hall of mirrors—deportation forces, spooked by their own likenesses, would infiltrate cities and neighborhoods, going door-to-door and business-to-business in search of unauthorized residents in keeping with a policy promoted to lift prohibitions on ICE busting into so-called “sensitive zones” like schools, hospitals, and religious institutions.

This special issue—borderS—in deliberate contrast, taps into radically distinct traditions and languages that cannot be pacified; that refuse to soldier on; that transmit messages against and beyond hetero-masculinist and homo-nationalist militarized-industrialized outer-range complexes. Tune in, read on, keep scrolling (get excited for Part II!): While the aesthetic, rhyming with the political per Walter Benjamin’s theses, is frequently a formula for authoritarianism; it’s also sometimes the very pharmakon we need, the paragon of Derrida’s parergon, the frame of the border, always-already undone, unmade, undocumentary, blessedly un-One.

Amy Sara Carroll and Ricardo Dominguez

Co-Editors, Issue 08: Borders

-

De la nada sale del sueño, de un sueño profundo, y explota en llanto. Nos despierta a Granola y a mí y tratamos de reconfortarlo, primero sin saber cómo y poco a poco, con el paso de los días, con consejos de gente viva que a su vez se lo dijo alguien que ya murió. Es el estómago, le duele al pasar gas. The process begins with the administration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists or antagonists to suppress the natural hormonal cycle. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) analogs are then administered to stimulate the ovaries to produce multiple eggs.

Lázaro nació en Santa Bárbara el día de la virgen de Guadalupe, su tío Alex le dice Lupillo. Para navidad ya conocíamos lo que nadie sabe qué es a ciencia cierta: el cólico. Fue nuestra primera navidad en casa, lejos. Si todo sigue cómo va, él crecerá en la costa central de California. Lázaro ya tiene pasaporte estadounidense y una tarjeta sentri para cruzar la frontera rápido. Once the follicles have reached an appropriate size, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is administered to trigger final maturation of the eggs. Approximately 36 hours later, a transvaginal ultrasound-guided needle aspiration procedure is performed to retrieve the eggs from the follicles within the ovaries.

Granola nació en Chula Vista, de padres mexicanos, niña ancla. Yo en Tijuana y fui adquiriendo documentos poco a poco. Throughout the stimulation phase, the growth and development of ovarian follicles are monitored using transvaginal ultrasound scans and blood tests to measure hormone levels. Lázaro fue hecho en México, específicamente en Tijuana, en una clínica de fertilidad en un edificio de ocho pisos cuyas paredes exteriores son de cristal, una incubadora gigante. Desde el lobby se puede ver una glorieta con un espigado Abraham Lincoln de cemento que sostiene una cadena destrozada. Todos los carros le sacan la vuelta. Semen samples are collected from the male partner or donor. The sperm are then washed and prepared to isolate healthy, motile sperm for fertilization.

En el vestibulo de esta clínica, mientras uno espera, uno ve gente de todos lados, colores y edades, más que un vestibulo de hospital, pareciera una sala de espera de aeropuerto internacional. La recepcionista contesta el teléfono con un inglés muy eficiente y da consejos de cómo llegar a la clínica lo más rápido posible. Abraham Lincon es un buen referente. The retrieved eggs are placed in a culture medium and combined with the prepared sperm in a laboratory dish for fertilization. Todos estos clientes buscan la fertilidad y la encuentran, o no, en una de las ciudades más peligrosas del mundo de las últimas dos décadas. Fertilization can occur through conventional insemination, where sperm are introduced to the eggs in the dish, or through intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), where a single sperm is injected directly into each mature egg.

Tijuana cada vez es más conocida por su turismo médico. Antes ciudad de vicio, ahora ciudad para mantener, mejorar o crear vida. Fertilized eggs, now called embryos, are cultured in a special incubator under controlled conditions to allow for further development. The embryos are monitored closely for signs of normal development and cell division. Tijuana ensambla generaciones de niños in vitro para exportación y desarrollo local. After 3 to 5 days of culture, one or more embryos of optimal quality are selected for transfer into the uterus. This procedure is typically performed using a thin catheter that is inserted through the cervix into the uterine cavity, guided by ultrasound imaging.

Lázaro no puede dormir porque tiene gases, muchos gases muy ruidosos, no necesariamente huelen pero rápido entendemos que sí le duelen. La explicación en internet es que su sistema digestivo no está aún completamente desarrollado, que él, más bien todos los bebés carecen de control sobre su esfínter y la violencia de sus flatulencias les causa mucho dolor. Following embryo transfer, supplemental progesterone may be administered to support the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and improve the chances of embryo implantation.

Granola, después de años de intervenir su cuerpo y abrirlo para extraer el que creció dentro del suyo, quiere dormir. Lázaro también quiere dormir pero el dolor no lo deja, llora muy fuerte, un estruendo que retumba el cuarto. Granola y yo nos vemos en la oscuridad y lo vemos a él, creemos que sigue dormido, que llora dentro del sueño. Approximately 10 to 14 days after embryo transfer, a blood test is performed to measure levels of the hormone human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which indicates whether pregnancy has occurred. Está en la frontera entre el dolor y el sueño del dolor, entre un dolor que viaja por el vasto subconsciente y el eco del dolor de nuestra limitada realidad. Creemos esto porque, una vez que despierta, que abre sus ojos, deja de llorar, ve nuestra cara de padres primerizos, viejos y preocupados, y como si todo fuera una broma, sonríe.

About the Author

At the turn of the twenty-first century I lived in outer boroughs; first Brooklyn and then Queens. Subways took me to work on The Hilly Island (Manahatta; Manhattan) via tracks that crossed one strait of the River that Runs Both Ways (Muhheakunnuk; The Hudson River) before slipping down under a twentieth-century midtown. Our offices were on the 21st floor of a building across from the Sheraton New York Times Square. Below, in the hotel’s basement, a friend’s uncle from the Dominican Republic worked in the laundry room. Down and up, midtown is vertical geography.

The Working Group had the goal of attempting to carve out a small space for genuine intellectual collaboration in the face of the inevitable fallout from Track Two, carril dos. Track One—the language is the US government’s—was to assassinate Fidel Castro. Track Two, socavar el régimen via “people to people contact,” which cast as suspicious all academic connections. Vaya, cualquier relación. For three years I traversed cubicles, looked down from giant windows on tidal regimes, and flew to Cuba on local carriers that departed from gates roped-off from the rest of Miami International Airport. A week before 9/11 I left New York. A decade passed. A friend, older than me, liked to chide it’s later than you think, chilling if cheap.

I returned to New York. One afternoon I left my new apartment on the border of Muhheakunnuk’s hurricane evacuation zone. When I exited the subway the buildings and sidewalks were the same, though no longer familiar. I looked at the clinic address on my phone. As I passed through the entrance on 52nd street and my body torqued through the same security turnstiles, the uncanny return clicked. Elevator doors opened onto the 22nd floor and onto a bright waiting room with southern views of the city: the same views as I had taken in many years before, but also not. The doctor’s office was a mix of taupe healthcare technology and shopworn décor. New York is expensive things teetering atop or stuck inside decaying infrastructure. The anesthesia was pleasant—no sense of time passing—and when I awoke eggs had been withdrawn.

About the Author

-

About the Author

About the Author

-

/ A Wet Aztec Letting Off Steam in the North (Google translation)

Materials: scaffold, ocelotl mask, self-portrait gloves, “Dreamer” maxtlatl, punching bag with miquiztli atltlachinolli, and Goodwill boxing shoes

About the Author

Year 166.666

It is known that in the dense green Sierra of the Pacifico in Mexico, there are rituals that involve jaguar-man in combat. The soil has been tilled for the new siembra (sowing), it is time for celebration, a new cycle begins. A loud crowd gathers in the middle of the plain, Jaguar-men are waiting around the circle, they are warriors, they wear boxing gloves sometimes, but others just bandages wrapped around their knuckles. The jaguar-head has a wide-open mouth, two eyeballs glowing in the dark. This ritual is ancient, it has been passed down through generations, it has survived colonial times. The first two jaguars step inside the circle, and the combat begins with some weak, loose moves, but slowly, the adrenaline takes over, and the soil claims the need for blood to have a good harvest. A single punch cracks the jaw of one fighter’s opponent, their bodies twist, the muscles shocked, tremble, and finally, sweat and blood spill out into the ground.

Knockouts

On another stage close to the border in Laredo, on the side of Mexico, a thirteen-year-old boy without resources started boxing as an amateur. Yes, one of the greatest glories of Mexican Boxing, el señor Luis Villanueva Paramo, the eternal, the immeasurable, and only champion: Kid Azteca! Tepito, the toughest barrio of Mexico City, saw the birth of Kid Azteca. This place is considered a cultural vortex, the heart of Teotihuacan. He migrated with his mom and brother to Nuevo Laredo in search of a better life; there, he discovered boxing as a ritual. Kid Chino his first nickname morphed into Kid Aztec, for his first combat in the USA when and where he emerged as an Aztec warrior. He survived two hundred combats and achieved one hundred and fourteen knockouts. One hundred and fourteen destroyed jaws. Pain, blood, and sweat stained the ring. He was known for his deadly hook to the liver. The ritual was organized into a spectacle that generates money, the ritual is now a sport mainly for men’s entertainment. The desire to beat, to watch, to rage, to laugh, and to suffer through pain is collective. We need idols, we need warriors.

Release the jaguar

What does the fighting life mean? Who needs to enter a battle and who watches? There are stages at home, where a sole dusty black punch bag hangs somewhere on the patio. The intimacy of rage, of releasing anger, of trying to break something or someone, there is no direct opponent. Who is your opponent? Is it an entity beyond the human, is it an oppressive system, is it life itself? Being bañado en sudor, being wet with your own sweat, being a wetback, sweat, and labor are connected, the hands bleed, the body keeps fighting beyond its own capabilities, and there is an energy that rises from the warrior’s ancestors, that keeps the beaten body moving despite extreme exposure to the sun, the hands are working the field. Maybe this is another form of ritual, maybe it is just another way of fighting back and release the jaguar.

About the Author

-

On October 15, 2023, Electronic Disturbance Theater (EDT) 3.0 and Annabel Turrado performed simultaneously on the border between Mexicali and Calexico during the 2022/23 MexiCali Biennial Land of Milk & Honey. I was one of the Biennial curators, and these recollections are gathered from my notes, recordings, and impressions that day.

Scene 1

A lone singer belts out ballads about heartbreak, boombox strapped to his body. He’s on the border in Mexicali, working Cristóbal Colón at Parque Héroes de Chapultepec. The NEW WORLD seems far from his mind, the BATTLE OF CHAPULTEPEC, too. He’s got his own line. He twirls and dips as cars inch toward the port of entry. They will always come. It’s an endless audience, a captive one, too — in many senses. Some give money. Others hum along.

Today, the drones hum, too. Electronic Disturbance Theater 3.0 shares the stage, performing a history of drone technology and border surveillance to a chorus of “What drones pollinate Imperial Valley?” and “What palindrones cross-pollinate the Land of Milk and Honey?”

As the drones get louder, so does the singer’s voice. A summoning. An “echology.”

Scene 2

A vendor sells raspados. Piña, fresa, limón y más. Her cart steers between car lanes, its umbrella as colorful as her iced delights.

Nearby, Annabel Turrado abolishes ICE. Her performance is an exercise in endurance. With raspadero in hand, she shaves down the frozen block. Every scrape conjures the end of the carceral state.

Turrado remains silent throughout. Both she and the ICE block melt in the desert sun, its rays reflect off a puddle and the sweat on her brow.

Viewers partake in the consumption of ice. An audience member makes their way to the vendor’s cart to buy a fruit-flavored snack. Later, a man at the park asks Turrado for shaved ice. She nods and fills his plastic bottle. “Un poco más?” She offers more. ICE melts in his water. The performance continues.

Interferences

Wearing red “MAKE AMERICA GREATER MEXICO AGAIN” hats and orange hazmat suits, EDT 3.0 performed scene three of “Three Echologies: An Á/Area/Aria X Play.” Half of the collective was positioned on the Calexico side of the border, the other half in Mexicali, a configuration that resembled past Mexicali Biennial performances such as Mike Rogers’ Telephone (2006) and Homeless Collective’s Transborder Game (2010). Their “palindrone” searched out, signaled, and shared the play with Homeland Security through an “echolocating” sound gesture that summoned subaltern knowledge of past, present, and future farmworkers, migrant laborers, and Zapatistas in an area reconfigured as X.

Down the street, Annabel Turrado’s durational performance Raspado: Abolish ICE took place simultaneously. For around four hours, the artist scraped away at a large, rectangular block of ice using a raspadero, a tool commonly used to make Mexican shaved ice. ICE refers both to the material used in the performance and to the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency that enforces laws governing border control and immigration, and trade and has been a key force in the increasingly violent surveillance, detention, and deportation of undocumented migrants.

The Biennial performances interfered with the everyday commerce and culture of Mexicali’s border zone – and vice versa. The acts of the performers, the labor of the singer and vendor, and the participation of the public combined in a grand gesture of frequency changes, frictions, and feedback.

About the Author

The Border as Parergon

. . . every analytic of aesthetic judgment presupposes that we can rigorously distinguish between the intrinsic and the extrinsic. Aesthetic judgment must concern intrinsic beauty, and not the around and about. It is therefore necessary to know—this is the fundamental presupposition, the foundation—how to define the intrinsic, the framed, and what to exclude as frame and beyond the frame.

Jacques Derrida, “The Parergon,” October (Summer, 1979)

In his essay on Kant’s concept of the “parergon” or ornament Derrida famously interrogates the status of the aesthetic as the necessary mediator between pure and practical reason. Even as the aesthetic seeks to challenge the violence of instrumental reason, defined by the ontological bifurcation between individual consciousness and the external world, it carries forward its own form of monological closure. Thus, Kant struggles to differentiate those modes of experience that are “intrinsic” to the aesthetic and those which are merely accessory. In this manner, Derrida’s analysis gestures towards a series of interrelated divisions; between art and vernacular culture, between art and activism, and between the artist and the broader public. Inside and outside, purity and impurity, art and not-art have become defining oppositions across the broader history of modernism. The US/Mexico border crossing offers a cognate geopolitical expression of this binary system. The border crossing is a liminal zone; a zone of mediation between two rationalist systems. It is a space of containment and canalization; of passage and the denial of passage; of inspection and surveillance, of sudden movement and inexplicable delay. But it is also a site of provisional community; bound together by shared subordination to the spatial contingencies of the state. What does it mean to “intervene” in such a space, far from the comfortingly familiar constraints of the institutional art world against which an “ornamental” criticality is so often acted out?

EDT 3.0’s play Social Echologies is performed within and beyond the border crossing. In the final act, the “Palindrone” hovers in the air, linking the two sides of the border through movement and transmission. Beneath it a singer entertains the slowly moving line of cars, accompanied by a boom box. Not far away Annabel Turrado methodically shaves down a large block of ice, creating raspados in the hot sun. Here “ICE” is melted down into refreshment for thirsty travelers awaiting the crossing. The pun and the palindrome co-exist as forms of wordplay. While the pun is defined by a generative dilation of meaning, in which one referent shadows another, the palindrome is defined by repetition and mirroring, as meaning remains unchanged from either direction. It suggests an ontological dynamic of sameness that parallels echo-location, in which the searching voice, like narcissus, is in dialogue only with itself. Social Echologies speaks of our transformation from “a species with roots” to a “species with antennas,” from a self defined by reciprocal integration with the world around us, to an identity that passively receives transmissions from a broadcasting center. The border zone is predicated on the containerization and fixity of subjectivity, between Mexican and American, between legal and illegal, between one self and another. The work of Annabel Turrado and EDT 3.0 ask how we might recover our rootedness in a broader community of resistance, while retaining our autonomy from the petrified forms of identity imposed by the border itself.

About the Author

-

i.

Useful choreography for crossing.

Safety first.

Remember that your body will be perceived as a potential threat before it will be perceived as the home where you reside. That is to say, you will be thought of as hard and machine-like and capable of violence before you will be thought of as irreverent, kind, funny or complicated—the things your body is capable of will be overdetermined by the fear of your Otherness.

This is why something like break-dancing or the moon-walk will not do. Ballet Folklorico and Danza Azteca either. To be certain, none of the great dances of the world are safe in this setting. They are too dexterous. The feet have inherited and accumulated too much practice. We try not to reveal the full potential of our steps outright.

Props can help. If you are a femme, carry a purse. If the sun shines brightly, carry a parasol. If the game is on, wear the right jersey and know the score. If you’re a student, carry books. If you are old and grandmotherly, walk with a cane.

For this interval of time perform what is expected. That is to say, view yourself from outside of yourself: from a mediocre perspective on the world and the capacities of its peoples.

In general, a right step then left step will do. Dexter, sinister, dexter, sinister, dexter, sinister. Toward another state.

ii.

We’re driving East on the 8 freeway toward the Imperial Valley. Sofia, our 19-year-old cousin, a bright spark of joy, intellect, and deep feeling, rides with us. We drive toward El Centro to visit our grandmother who is receiving hospice care there.

From the back seat, Sofia asks us to tell her family gossip and to explain pieces of family history that she doesn’t have context for. She wants to know how we ended up here and why.

We tell her family migration stories; we tell her how after moving from Sinaloa to Mexicali with her sister our grandmother worked in a pharmacy. We tell her how our bisabuelo was a traveling merchant. “That’s such an old-timey job!” she laughs.

The chatter in the car stops when we see a group of migrants detained in an open-air camp in the distance. They are huddled and dwarfed by the horizontality of the landscape and the shadowy mountains looming in the distance. We fall completely quiet.

We break the silence to acknowledge the guilt we feel for being able to travel freely with people we love. We tell Sophia about how the 8 freeway is called the Kumeyaay Highway because it was built over ancient Kumeyaay routes used for seasonal migration and trade that linked the desert, to the mountains, to the ocean. And, how these routes were connected to trade networks linking Indigenous communities in the US Southwest with those in central Mexico – cultural and economic links fostering movement, connection, sustained by traveling merchants that were part of the pochtecayotl.

We tell her that when we drive along this route, we can’t help but think about this history, and, how the border is a colonial tool for severing.

“Like driving along the edge of a blade,” she says.

iii.

We made fleeting friendships at the improvised humanitarian aid center set up by mutual aid organizations in San Diego to receive hundreds of migrants who had recently crossed the border to request asylum. To broker such friendships, we became adept at circumlocution, speaking around lexical gaps, in Broken French, Broken Chinese, Broken Arabic, Broken Portuguese.

Before the city or any other governmental entity mobilized, we were among many community members who volunteered as first responders to a crisis manufactured by the State in the Fall of 2023. The dehumanizing treatment by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) required various forms of triage, field hospital(ity) work.

One morning we arrived with a cooler filled with egg, cheese, and potato breakfast burritos that we made so people arriving at the trolley station could have something warm to eat. A trio of young Senegalese men approached our table. We pointed to the sign that we’d printed with line drawings of an egg, cheese and a potato and explained that this was a Mexican breakfast food, “Burrito. Petit déjeuner!” They each took one and thanked us in a mixture of French, Spanish and English, but looked at the burritos suspiciously.

Later, as we sat with another group of compas from Colombia who discussed how San Ysidro looks and sounds a lot more similar to Mexico than they expected – in a mostly amused tone with perhaps a touch of disappointment – we saw one of the Senegalese travelers wave to us. “Muchas Gracias! Mexico is best breakfast!” he shouted. To our delight we saw that he’d taken another burrito for the road.

“De rien, amigos. Bienvenidos!” we shouted back across the parking lot, as they departed to continue their journey, with an end of the line in sight.

About the Author

I was drawn to Cog•nate Collective’s response for its attention/tension in relation to the complexity of “border narratives” and the way that language moves, transforms, and transfigures. The contrast between the intimacy of the anecdotes that open their piece and the generalizations of the graphics struck me as particularly poignant, especially in relation to the border as a site of dehumanization, the border as an horrendous act of resignification. I responded with language and image, using collage because of its insistence on materiality, its disruption of representation.

About the Author

-

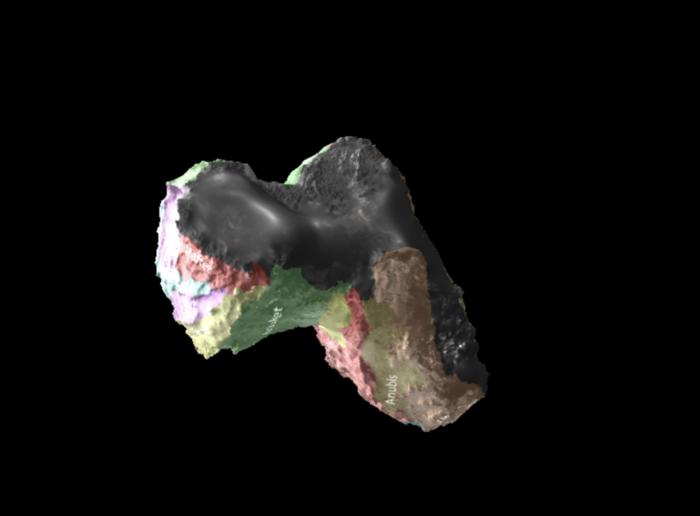

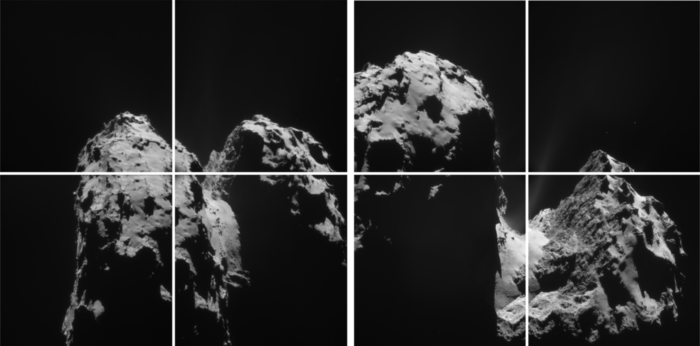

[ a comet enters ]

[ entra un cometa ]

Plasma.

Hielo y piedra.

A small body composed of ice and rock.

Gas.

This is comet 67P, the singing comet. De familia joviana. De Júpiter.

A jostling electromagnetic wave covers the surface de los otros cuerpos presentes.

Alguien respira cerca del núcleo. Breathe outside the nucleus.

[ el comienzo de la obra ]

[ the play starts ]

El sonido cae como la imagen: eco roto.

What’s in a sound that comes from afar?

[ barely perceptible ]

A hand holds a word,

co-me-ta

c-o-m-e-t-a

It holds it as it holds air, gasping to say aloud “cometa que canta.”

This is a code to bring back the fragments, weaving the same electromagnetic field by opening the mouth de esquina a esquina.

La superficie de la lengua se vuelve gaseosa. The tongue extends into the emptiness of the stage.

No props.

In the center, not the nucleus. The nucleus is in a corner, there, ahí …en la esquina flameante.

La boca, the mouth fills the space.

Los dientes son superficies reflejantes; generan calor; rompen materia.

La saliva se arremolina para preguntar por los sonidos que vienen de lejos.

Rosetta en los surcos de la lengua.

[ On stage, the question of tone ]

Cómo se dice cometa. Cómo se dice cometa. Cometa se dice cómo.

Jolted out of the sun, the cold body shrieks.

Jolted out of the mouth, el sonido se quiebra.

The song quivers y permanece en el espacio.

El cruce húmedo, desbocado de la lengua produce una piedra.

Spit the stone.

Escupe la piedra ardiente and sing.

Split the flaming rock.

[ Fin ]

[ End ]

*images from the European Space Agency (https://rosetta.esa/int)

About the Author

tras bambalinas : backstagethree characters over factual audio excerpt (stage hand, prop maker, flyman)—floodlights on—I don’t get it.What?No props: that’s stage direction, means either I won’t be working much, or they’ll use ancient props.No, it’s part of the play: Learn to read.No seas mamón.Stop it!Well, the rig job’s crazy! Gotta develop a whole civilization to get a camera there. Getting everything in place for last call takes millions of years.See, those are my props. There are props.Shit, it’s as nerve-wracking as it is exhilarating. The political will and the crew to get money lobbied, to set lights there.Whitey is on the moon. Gaza’s on the news. The comet is screaming. Did you like the soundtrack?Comes with a soundtrack?Yep, and some nice reviews: This comet is singing it’s heart out! according to YouTube.Who captured the electromagnetic oscillations?That’s also a prop.It’s a translation: from electromagnetic oscillation to almost musical —alien— clicks. Alien tempos, no refrains.What do you mean the comet is screaming?Didn’t you look at it?Nope.The head shot! Which head shot?Third quadrant, left to right! See? The cometa grita.If you had run the oscillations through death metal AIs you could hear a scream, and not these reassuring clicks. If it’s a song, it’s a screaming song.Are AIs props?Kind of. Now run it through Spanish.Ok, cometa is kite in Spanish is papalote, from náhuatl papalotl, which is butterfly.A comet a kite a mariposa.Now backwards through Greek.OK: Cometa comes from como, Greek for cabellera, a sparkling body of hair, a tail, a cola de luz.Cometa es cabellera.I don’t see any hair: looks bald to me.Creamy meringue stubble.That’s the other mug shot, another translation.I’ll charge overtime, surely.Cometa is a thing that flies and flows and flutters and twinkles.Wait, maybe it’s not screaming. Maybe it’s yawning. How long has it been over there? Since the Big Bang? That’s a long time. Maybe it’s bored.Please don’t start with that character development shit, you always do that!Ok, what if it’s hungry? What if it travels throughout the cosmos looking for things to eat? It’s a starving maw that wants to swallow the cosmos!You’re getting delusional again! Here’s your pills: take one.That’s the question, how does a comet eat? How to swallow kites. Sorry, wrong filter. Cómo come cometa.Keep it down, don’t shout.I see four faces: maybe it’s a chorus? One of them looks scared.Don’t mind them, they’re secondary characters.Yep! But what’s the motivation?Don’t go into that rabbit hole, please. It’s clear as rain: read the script, it spits. You get to know at the end. It spits its pit sit spit it spitsitspi tsitsipitsitstipsitspitsitspitsitspitsitspitsits.Now look what you’ve done! Can you smack him, please?It’s your fault. I haven’t done anything!It’s always the same. You just can’t reason with some people.You know what, it’s late, let’s call it a day. Did you take your pill?Ok, that’ll help you get some sleep. Good job guys, nice to talk shop.—as characters go out, we hear the original soundtrack: while offstage, a character is still going t spits its pit sit spit it spitsitspi tsitsipitsitstipsitspitsitspitsitspitsitspitsitself —

The cometa grita.If you had run the oscillations through death metal AIs you could hear a scream, and not these reassuring clicks. If it’s a song, it’s a screaming song.Are AIs props?Kind of. Now run it through Spanish.Ok, cometa is kite in Spanish is papalote, from náhuatl papalotl, which is butterfly.A comet a kite a mariposa.Now backwards through Greek.OK: Cometa comes from como, Greek for cabellera, a sparkling body of hair, a tail, a cola de luz.Cometa es cabellera.I don’t see any hair: looks bald to me.Creamy meringue stubble.That’s the other mug shot, another translation.I’ll charge overtime, surely.Cometa is a thing that flies and flows and flutters and twinkles.Wait, maybe it’s not screaming. Maybe it’s yawning. How long has it been over there? Since the Big Bang? That’s a long time. Maybe it’s bored.Please don’t start with that character development shit, you always do that!Ok, what if it’s hungry? What if it travels throughout the cosmos looking for things to eat? It’s a starving maw that wants to swallow the cosmos!You’re getting delusional again! Here’s your pills: take one.That’s the question, how does a comet eat? How to swallow kites. Sorry, wrong filter. Cómo come cometa.Keep it down, don’t shout.I see four faces: maybe it’s a chorus? One of them looks scared.Don’t mind them, they’re secondary characters.Yep! But what’s the motivation?Don’t go into that rabbit hole, please. It’s clear as rain: read the script, it spits. You get to know at the end. It spits its pit sit spit it spitsitspi tsitsipitsitstipsitspitsitspitsitspitsitspitsits.Now look what you’ve done! Can you smack him, please?It’s your fault. I haven’t done anything!It’s always the same. You just can’t reason with some people.You know what, it’s late, let’s call it a day. Did you take your pill?Ok, that’ll help you get some sleep. Good job guys, nice to talk shop.—as characters go out, we hear the original soundtrack: while offstage, a character is still going t spits its pit sit spit it spitsitspi tsitsipitsitstipsitspitsitspitsitspitsitspitsitself —

About the Author

-

Imagining the fiery ends of a border, surrogates ignite their bordered selves.

Sherwin Bitsui’s Dissolve drifts over the precipice of alchemy’s endless poetry.

A palimpsest of images.

The third research installation for AR:7.

Surrogates peer into an open flame.

A cosmic egg.

Burning phoenix to ancestral.

A study in anamnesis and futurity..

About the Author

About the Author

-

by bruce ludd y nadie nada / saúl hernández-vargas

sí, pero, ¿qué es esta imagen? ¿qué captura esta imagen, en blanco y negro, tomada por un fotógrafo anónimo que vivió y trabajó en los últimos años del siglo XIX? ¿qué nos dice aquel paisaje habitado por plantas flacas y testarudas, similares a las crecen entre tijuana y san ysidro? ¿qué nos dicen, si nos dice algo, esa yerba, ese mezquite, ese cadillo?

*

sí, pero esta imagen, además, captura el momento justo en que ocurre algo. Ago, en efecto: justo en el centro, una carretilla de madera carga un obelisco de concreto, manipulado por tres hombres que visten de camisas claras y sombreros de copa. robusto como ellos, el monumento está sostenido por unas poleas ancladas a la tierra seca y por las cuerdas de tres hombres que visten de forma parecida: pantalón, camisa, sombrero alto. y mientras tanto, a su alrededor, otros cinco, dispersos en el espacio, pero atentos como testigos, completan la escena. ninguno de ellos intenta relacionarse con quien los mira ni mucho menos con quien registra ese momento preciso. y quizás por ello es evidente que allí, en ese momento preciso, visto desde ahora, ocurre algo: no nos referimos a la suspensión fotográfica, ni a la teatralidad del gesto y de la pose. no nos referimos tampoco a la importancia que tuvo en el siglo XIX ni a inicios del siglo XX la fotografía como acontecimiento, casi siempre como privilegio y prerrogativa de las clases altas y de las instituciones del estado encargadas de vigilar, clasificando y reduciendo, maniatando primero con la mirada. lo que ocurre en esa fotografía es el por-venir: una fisura y una grieta

*

sí, comúnmente es así, comúnmente esa imagen es vista así: como una imagen del pasado, que certifica la producción material de la línea fronteriza. entendida como testigo, esa imagen hace visible el momento justo en que cinco hombres colocaban el obelisco para decir: aquí termina un territorio y empieza otro. y sí eso es cierto, ellos fueron los encargados de hacer visible una línea fronteriza que, hasta ese momento, sólo existía en el papel, sólo había sido imaginada por políticos, militares, agrimensores e ingenieros en documentos como el tratado de guadalupe, que concluyó la guerra entre méxico y los estados unidos (1846 y 1848). esta fotografía, dice la mirada dominante, testifica el momento en que un grupo de agentes del estado colocan un obelisco para decir: aquí termina un territorio y empieza otro

pero para nosotros, en esta fotografía no es claro si quienes están allí, rodeados por ese paisaje seco, por yerba, por ese mezquite y ese cadillo, están colocando o retirando el obelisco que, unido a muchos otros, alguna vez fue fin y principio del estado-nación, de sus leyes, de sus sueños y de sus relatos fundacionales. para nosotros esta fotografía es una imagen del por-venir, una imagen liminal en donde no es claro si los hombres que están allí, trabajando unos con otros, anónimos por culpa de los años y por la falta de contexto, están colocando el monumento o, si por el contrario, lo están retirando, extendiendo el horizonte, liberándolo.

Photo: Jasmine Cogan ¿y qué se libera con el horizonte? desde nuestro punto de vista, la narrativa que emergió durante la posguerra acerca de los estados nacionales como entidades que para existir necesitaban bordes y murallas. ni murallas.

y si el historiador del arte georges didi-huberman está en lo cierto, y la imaginación es “nuestra comuna”, “nuestra primera facultad de sublevación”, esta imagen del siglo XIX es, como decimos, una fisura o una grieta en la que aparece y se ilumina otra frontera posible: estados nacionales no amurallados ni fortificados y, mejor aún, otras formaciones sociales y políticas que no estén fundadas en la predilección del siglo XIX por ese tipo de formaciones expansivas y voraces, monstruosas, como leviatanes.

About the Author

piedra

Cabe la posibilidad de que el negativo de esta fotografía se corresponda con el registro invasivo de una ceremonia ancestral. Por tanto, no es un obelisco el que miramos, sino una piedra de quince por diez pies excediendo el horizonte. Un bloque de granito tallado por el sol. Yace en mitad del paisaje como para protestar: no nos moverán. En plural. Sin fantasmas, sin quemaduras, sin sombras. Los primeros en advertir sus dimensiones son los microorganismos en torno a la piedra que se dejan ver sin que puedan mirarse hacia adentro. Lagartijas repudiando el plástico. Antílopes llevando en sus hocicos cuerdas de embalar. Buitres sobrevolando algún animal en proceso de descomposición gracias al esmero de las hormigas. La luna que se aleja en sentido opuesto a la oscuridad masiva y los insectos.

Cada mañana, la piedra registra huellas de pájaros, cangrejos y coyotes. A veces aparecen las marcas reversibles de ríos lejanos, como vetas que revelan su antigüedad y todo lo que se dejó atrás: sube la cadera, mete la barriga, no hables para poder cruzar. En el negativo de la imagen, la piedra parece un fetiche cuya singularidad es incapaz de obligarnos a mirarla de otro modo. Que los hombres la carguen a trocha abierta y la coloquen a la mitad no subrayaría ningún cambio de paradigma. Vista a lo lejos, la piedra puede ser :solo en apariencia: un monolito derivado de la extracción, una modalidad jurídica, un ejercicio de gobernanza. Pero un sarcófago, como la muerte, siempre contiene la latencia de lo vivo. Y la fragilidad del sistema siempre está sostenida por la fuerza del sistema.

Es entonces cuando percibimos que la piedra ha sido arrancada de otra vida que no ha llegado aún pero que vuelve. Liberado el ojo, la piedra, por la imparidad de sus limos, relata lo que tardó millones de años en sedimentarse para adquirir esas formas. Hay que contar los pasos, saber su posición relativa, acercarse a ella, cavar un hueco en el lugar exacto y dejarse enterrar, como lo dice el rito.

Primero es la voz como una forma de reorientación, cuando el cuerpo se mueve sin mapa, empujando la carne hacia abajo. La voz nunca es presente sino resonancia libre de costuras: nunca lo que entra por el oído tiene origen nítido o contornos estables. Menos develar que seguir el rastro hacia la inminente mutación ambiental. No es pararnos en la punta de la piedra para ver las montañas de un país y las colinas holográficas en el otro, una prueba de la línea divisoria y su fragilidad discursiva, no. Ni las criaturas mullidas por los químicos para las cuales la fantasía de la frontera no es opción. Tampoco las relaciones asimétricas que determinan la exclusión histórica de la piedra misma (la piedra no está en busca de trabajo).

Es sentir en el empeine el leve movimiento del subsuelo, los ritmos retoñantes que se anteponen a la velocidad del capital a punto de invocar la depredación. Procede luego tocar su línea interminable, catar su sabor húmedo, oler las flores de sus bordes, amar su casa oscura donde buscamos refugio. Hundir la mano en la hoguera de la roca y tocar sus huesos que soportan lo mismo que la noche soporta las máquinas de matar. Después, dejar que la piedra amarre nuestras lenguas para untarnos otro idioma. Desarrollar el deseo pero nunca el método. Asegurar que la imagen reflejada en su granito muestre el mismo rostro del día anterior y de todos los días anteriores a éste. Tirar al cielo la ira del duelo, los sufrimientos que nos rompen, para que la piedra caiga al rumor del río, una manera de suturar la herida, de limpiarlo de las aguas residuales. Toca entonces, finalmente, escuchar a la piedra, sus esquinas remotas cuya capacidad de desvío narrarán la larga letanía de su peregrinaje.

About the Author

-

About the Author

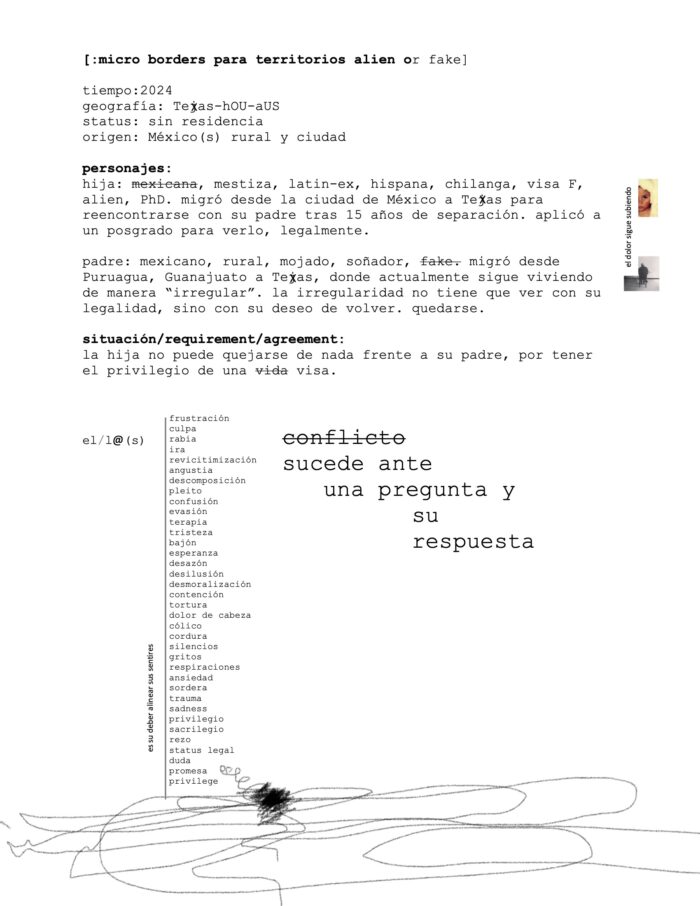

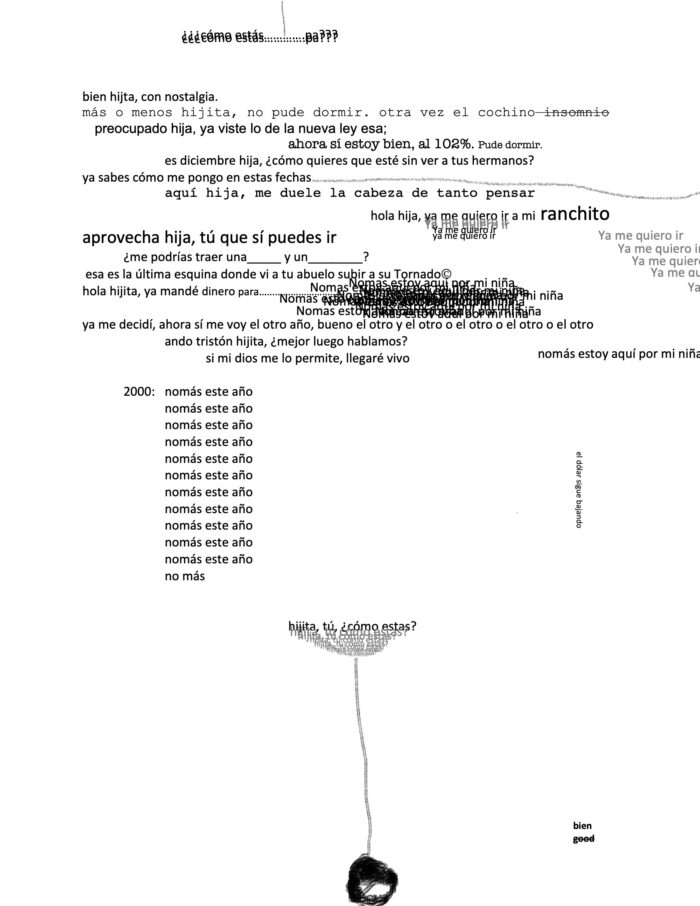

Maribel Bello’s poetic-dramatic-dialogue, “[:micro borders para territorios alien or fake]” demands that we inhabit uncertainty, misunderstanding, discomfort, and irregularity. This is true because it focuses on the relationship between a “visa F” daughter pursuing her PhD in the US and her “mojado” father, which has been fractured “tras 15 años de separación” due to undocumented migration, but also because the language, genre, style, and even the font of the piece is constantly shifting and unstable. As such, “micro borders” requires that we occupy the condition of migration and the role of the migrant in the aftermath of forced family separation and tentative reunification. Like the relationship between hija y padre in “micro borders,” neither the condition of migration nor the piece itself follow a coherent narrative or point towards any kind of resolution. They are irregular, a word that Bello refers to when she introduces the father as one of the two “personajes” of the poetic-dramatic-dialogue, alongside la hija.

The notion of “lo irregular” stands out because it is one of several examples in the piece of a word or idea that could seem to mean one thing but actually means another; that refers to multiple meanings at the same time; or that could be written in either Spanish or English. Bello tells us that the father, who migrated from Puruagua, Guanajuato to Tej/xas (she layers the x over the j as if correcting her language from Spanish to English), continues to live there “de manera ‘irregular.’ la irregularidad no tiene que ver con su legalidad, sino con su deseo de volver. quedarse.” It is telling that Bello is compelled to correct any assumptions about the father’s irregular status in terms of his legal right to be in the US. We understand that the father is undocumented, since the daughter “tiene el privilegio de una vida visa” while he constantly fears deportation and cannot leave the US. But the true meaning of his irregularity lies in his conflicting desire to both return to México and to stay in Texas; to be with the daughter he has finally reunited with and to be with his other children who remain in México. The contradiction that the father lives reminds me of the condition of being “ni de aquí, ni de allá” that many migrants and Chicanxs/Latinxs identify with, but his undocumented status legally bars him from occupying either American or Mexican space. For the father, to be “ni de aquí, ni de allá” is a literal condition that never has the privilege of metaphor.

Such irregularity persists and multiplies throughout the piece, constantly highlighting barriers that return us to the conditions of il/legality and undocumentation. But the irregularity of migration and the migrant condition also reveals unexpected possibilities. Although family reunification is certainly an expected reason for migration, Bello proposes a means of reunification that the media and general public rarely consider, through the daughter’s PhD studies with her “visa F.” Postgraduate study becomes more than just a path to a degree or career, it is way to control the process of migration, making it legal and choosing the location to be close to the father. Dominant media narratives don’t accept the image of a young mexicana, mestiza, latin-ex, hispana, chilanga daughter pursuing a PhD in the US, or having choice and control over their migration process.

And yet, despite the choices and control available to her, the daughter’s emotional – and metaphorical – barriers stemming from migration resemble those of her mojado father. Just as the father’s un/documented status is uncertain – for he can never be sure what “la nueva ley esa” will mean for him – the relationship between father and daughter is uncertain. Their relationship, which bears the trauma of 15 years of separation, is contingent upon not talking about certain feelings and emotions, although the daughter especially feels constrained because of her legal status. Bello lists the forbidden feelings and emotions between hija y padre in the piece, but crosses out the word conflicto, possibly as a sign of the missed opportunity to explore her trauma and pain with the father. Despite, but also because of their common trauma, hija y padre are unable to truly communicate with each other. The things they cannot talk about are mostly in Spanish: “frustración,” “culpa,” “rabia,” “ira;” with just a few in English: “sadness,” “privilege,” perhaps representing feelings and conditions that the father would be less able to understand. A few of the things they cannot talk about could be read in either Spanish or English: “trauma,” “status legal,” perhaps representing feelings and conditions that affect them both, across borders. But the distance between hija y padre is much more prominent throughout the piece, variously reflected through their roles as “personajes” in a performance-like setting, the intersecting and clashing vertical and horizontal text, or the scribbles and black blobs at the bottom of each page.

Thus, “micro borders” insists that not only are the dominant narratives about undocumented migrants and migration usually wrong, their “real” or true stories are very often illegible and unknown, even to the migrants themselves. Bello demonstrates the illegibility and irregularity of these stories and relationships through the black scribbles and blobs at the bottom of each page. When the father finally asks his daughter, “hijita, tú, cómo estas?,” there is only one acceptable answer: “bien good.” But the illegible, unspoken truth literally lies beneath the question in a form of a menacing black ink blob, precariously balanced on the thinnest line of text. While the black blob may be illegible, it is definitely visible, revealing the trauma that la hija, el padre, and all migrants and family members touched by un/documentation hold inside, waiting to burst forth.

About the Author

-

EL VIENTO SURGE DEL FUEGO, el fuego se aviva al aire y el fuego se representa en forma de X, X como la X transfronteriza de Sebastián, que es el emblema de Ciudad Juárez y se ubica en la zona norte, a un costado del muro que divide los Estados Unidos de Norteamérica de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Una X Xichanista. La X que es la marca de un tesoro en un mapa, el cruce de caminos de un tren o una cicatriz. Otro de los límites entre estos países se ubica al oeste del Río Bravo, Anapra, una de las zonas más marginadas de Juárez donde el sabor del metal es un otoño de yonkes, yonkes tumba donde se abandonan los cuerpos de las desaparecidas, como los deshechos de un alfabeto violento. En el momento en que escribo esto, durante el perihelio anual, Juárez encabeza los casos de feminicidio en México, otra vez, y el crimen del 27 de marzo de 2023 donde fallecieron cuarenta migrantes en un centro de detención ilegal del Instituto Nacional de Migración, también en Juárez, sigue impune. Del lado mexicano del puerto de Anapra, el muro versa, gracias a un grafiti: «Ni delincuentes ni ilegales, somos trabajadores», junto al dibujo de un Ku Klux Klan. La X también es lo desconocido, lo inclasificable, lo anónimo.

El acero del muro resuena hueco cuando es percutido por la piedra y frotado con varillas. Su eco, tom-tom, se confunde con el sonido elemental del tren y este, a su vez, con el del poniente. El tren también es un personaje anónimo, un tzompantli. Del otro lado, está Sunland Park, ahí frente donde se erigió, en mayo de 1911, el Palacio Nacional durante la Revolución Mexicana, una diminuta casa de adobe. Aquí se encuentran Chihuahua, Nuevo México y Texas. Aquí el linde es polvo, ruina y crepúsculo de lo que quiso ser país. Un silencio in-tren-minable que nos desplaza. Aquí, 31°47’02.0” N 106°34’27.9” W, con una grabadora ZOOM H4n y micrófonos de contacto, colegas y yo, dirigidos por Facundo Torrieri, captamos las vibraciones de la superficie metálica del muro para el laboratorio de formación sonora y creación fonográfica, Sonografías Chihuahua, que dio pie a una pieza que se exhibió en concierto en el Teatro de Cámara Fernando Saavedra, en Chihuahua, meses después. En la edad de piedra, los megalitos se tocaban para alterar conciencias, durante rituales de paso. Hoy este muro es un vórtice silbante, un passageway que nos acerca a las experiencias de la muerte en el desierto, el extravío. Su litofonía es campanada. ¡Tan-tan! ¿Quién es? Estertor sin fin. Irrefrenable.

About the Author

About the Author