05

Curating

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. — Arundhati Roy Back in March 2020, when a staggering wave of cancellations hit the performing arts field, curator and contributor to […]

-

Ron Berry

Editors

Anna Gallagher-Ross

Theatres

- 1.Lengua materna / Mother tongue

- 2.Toward a New Curation

- 3.The Storehouse: A Live Magazine [Manifesto Excerpt]

- 4.Yeah, I Said It. Suck Your Mum.

- 5.How can we rehearse for a future we don’t have an image of?

- 6.the theatre that I do not wish to imagine but wish to have

- 7.The Fellowship

- 8.performance score built with undated performance notes

- 9.WHAT TIME IS IT?

- 10.THE GLOSSARY

- 11.The Flowers of Manshiyat Naser

- 12.night dreaming

- 13.A Meniscus Around My Fingers

- 14.feast

- 15.WEST END EATS ITSELF IN GAY PC SNOWFLAKE BLOODBATH SHOCKER

- 16.Work-in-Progress

- 17.Wishful Thinking

- 18.ingat (to take care)

Prologue

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.

Back in March 2020, when a staggering wave of cancellations hit the performing arts field, curator and contributor to this issue, Lisa Gilardino wrote us from Italy about a colleague who ran a festival in Bergamo. He had said that it seemed as if the sea had withdrawn and that we were now able to see the seabed and everything it contained. Lisa was sure that in this moment of clarity we would discover hidden treasures, that “together we’d find something we didn’t even imagine before.

We’ve carried this image of the tide and the seabed with us ever since, as our world was swept by COVID-19, and, as of writing, we are still living through it’s fallout. We have also witnessed the murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Rayshard Brooks, and others by police, and the rising of Black Lives Matter protests, not only in the United States but across the globe, creating what is being called the largest civil rights movement in history. In the heave of lockdown and protest, and with a crucial U.S. election just a few weeks away, this is a time of exhaustion, anger, grief, and anxiety, but also one that is surging with momentum, collective awareness, and hope.

These two pandemics, that of COVID-19 and of systemic racism, have laid bare the truths we have known for a long time. We have seen the inequality and unsustainability of the performing arts field. How we need to better support the arts ecosystem of artists, administrators, technicians, producers, designers, directors, and beyond — so many of whom are precariously employed. How we are complicit and, as contributor Shanta Thake so aptly writes, “in partnership with” white supremacy, and urgently need to reallocate power and resources in our field. Perhaps we must reimagine it entirely. The tide is finally out and we cannot look away.

Work on Imagined Theatres Issue 05: Curating Performance began in September 2019, a period now known as the “before times.” Back then, we sought to hear from curators, artistic directors, producers, and arts administrators about what they imagined for the future of our field. We reached out to colleagues, and colleagues-of-colleagues, across the globe, asking them to enter into dialogue about their hopes and dreams for the future of the performing arts. We wanted to weave this issue from a series of dynamic encounters: placing curators of small institutions, artist-run centers, and festivals in conversations with colleagues at major museums and institutions; those early on in their careers with those who’ve contributed to shaping the field for more than twenty years; as well as incorporating a diverse set of geographies, knowing, of course, the impossibility of capturing the field as a whole. We see this as the start of a conversation about what curating performance, and performance itself, can be in the future.

Adopting a call-and-response structure, eighteen colleagues were asked to write the first round of imaginings, what we call “Theatres.” We then paired each of them with another colleague who would write a response, what we call a “Gloss.” Little did we know that this issue would, in form and content, straddle a historic moment that we’re still living through: with the initial contributions written before COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter protests, and their responses written in the wake of these events.

This issue, which features a range of creative reflections, musings, and calls to action, invites us to step through the portal, and encourages us not to look back, but rather forward, to imagine a set of possibilities that will shape the future shoreline. This issue asks: how can we “together find something we didn’t even imagine before?”

We are eternally grateful to the colleagues who generously accepted the invitation to imagine with us.

—

October 23, 2020

Anna Gallagher-Ross and Ron Berry

Co-Artistic Directors, Fusebox Festival

Co-Editors, Issue 05: Curating Performance

-

Buenos Aires, 12/2019

Teatros imaginados y deseados. A veces estoy en ellos. Subida. Montada. Pero cuando no hay público. En general en horarios extraños. Cuando los sonidos de las calles refieren a actividades de la vida cotidiana. Se compran, colchones, estufas, refrigeradores … Hace 20 años llegué a un teatro que nunca había imaginado. Pero parecido a muchos otros en los que había estado. Ese nuevo teatro me llevó a este futuro que hoy vivo. Muchos teatros que siguen apareciendo. Incontables. Ahora vivo en la ciudad que más teatros tiene — o por lo menos eso dicen — y trabajo para una ciudad en la que la gente de teatro está uniéndose y formando una gran coalición, luchando por sus derechos. Mi padre viene de un país donde en los teatros ahora se debate el futuro de una nación. Mis hijxs han crecido acompañándome a los teatros. Me enamoré de mi marido en uno de los teatros más lindos del mundo. Entonces, no imagino un teatro, vivo, respiro, sueño teatro. Pero si aún así tuviera que imaginar, entonces quisiera imaginar que las lenguas que han sido olvidadas, aquellas que se siguen hablando en muchas partes del mundo, formarán parte de la nueva dramaturgia. Una dramaturgia donde las lenguas dominantes dejarán lugar a las lenguas que casi nadie habla. Esas lenguas originarias que lentamente están siendo rescatadas por varixs artistas en todo el mundo. Ese es el teatro que imagino. Uno donde nos sentemos a escuchar el renacimiento de esas lenguas.

Imagined and desired theaters. Sometimes I am on stage. Off stage. Backstage. But when there is no one to see me. No audience. Most of the time at odd hours. The sounds in the streets are sounds of everyday life. Se compran, colchones, estufas, refrigeradores… Twenty years ago I arrived at a theater I had never imagined before. Yet it looked like many theaters where I had been. That new theater took me to this future, where I am now. Many theaters after that. Too many to count. I live in a city that has more theaters than any other — or at least that is what they say. I work for a city in which its theater community is uniting unlike any other time to fight for their rights. My father comes from a country where right now people are in theaters debating the nation’s future. My kids have grown up in the various theaters where I have worked. I fell in love with my husband in one of the most beautiful theaters in the world. I do not imagine a theater, because I live theater, breathe it in and out; I dream it. But, if I had to imagine a theater, then I’d like to imagine that the languages that have been forgotten, which are still spoken in many parts of the world, would be part of this new playwriting. A playwriting in which dominant languages make space for the languages no one speaks; those original languages that are slowly being rescued by various artists around the world. That is the theater that I imagine. A theater where we could listen to the rebirth of those languages.

Translation by Alexandra Ripp.

About the Author

Historias mínimas

Nací y crecí en tierras australes que fueron habitadas por Selknams, Yaganes y Kawéskar; en una ciudad donde no había teatro. Tengo un apellido Mapuche pero no hablo la lengua de mis ancestros.

Me encantaría soñar en mapuzungun e imaginar futuros posibles junto a mi hijo en dicha lengua.

Sin embargo, hace dos noches muchos hombres salieron a las calles creyéndose dioses y quisieron repetir la horrible historia de nuestro pueblo; emulando a los conquistadores, armados con palos y piedras, arremetieron contra dirigentes Mapuches que hasta el día de hoy luchan por sus derechos.

¿Qué hacemos con tanta miseria? ¿cómo sobrevivimos a tanto nacionalismo barato? Han pasado siglos en los que los poderosos han contado y tergiversado la historia y ya no basta con imaginar. Es tiempo de contar todas esas historias mínimas que aún no han sido contadas. Entonces ya no seremos espectadores de la historia de unos pocos, sino que seremos protagonistas de la historia que queremos.

Hace varios años un sabio dramaturgo chileno escribió a propósito de Chile: “un infierno que se sostiene a fuerza de milagros, una esperanza seca que perdura”… creo que esta expresión nos hablaba de cómo lo imposible puede sobrevivir a fuerza de amor. Una característica que ha marcado al teatro por décadas en muchos países, es su condición de ser un espacio que nadie entiende cómo se mantiene en pie, sino es por la convicción de quienes en él se desempeñan.

De esta manera, en un mundo atravesado por una pandemia, llenos de incertidumbres y dictaduras disfrazadas de democracia, me atrevo a convocar desde la convicción que me da el amor a nuestro oficio para que no imaginemos teatros sino que los creemos y los multipliquemos.

Nacen teatros donde se escuchan y recuperan las lenguas de nuestros pueblos indígenas. Al otro lado de la montaña nacen teatros que cuentan la historia de nuestros ancestros que no fueron héroes. En una serie de islas perdidas en el mar nacen teatros amateurs, de barrios, de comunidades migrantes, de sobrevivientes de todas las batallas posibles de esta travesía llamada vida.

El teatro es nuevamente un lugar de reunión y de reflexión no sólo para las élites, sino para todas y todos. De esa historia es de la que quiero ser parte junto a mi hijo.

Me atrevo a invitar a tod@s a esta re-construcción postpandémica, que sea el teatro el lugar de las historias mínimas, un lugar cuya brújula sean las palabras: Amor, Respeto y Comunidad.

dedicado a Frie Leysen

Small Stories

I was born and grew up in southern lands that were inhabited by the Selk’nam, Yaghan y Kawésqar peoples, in a city where there was no theater. I have a Mapuche last name but I do not speak the language of my ancestors.

I would love to dream in mapuzungun and, in that language, imagine possible futures with my son.

However, two nights ago, many men went out into the streets believing themselves gods. They wanted to repeat our country’s horrible history, emulating conquistadors, armed with sticks and rocks, attacking Mapuche leaders that are still, to this day, fighting for their rights.

What do we do with so much misery? How do we survive all this cheap nationalism? Centuries have passed in which the powerful have told and twisted history, and now, imagining is not enough. It’s time to tell these small stories that still have not been told. Then, we will no longer be spectators of the history of a few but rather protagonists of the story we want.

A few years ago, a wise Chilean playwright described Chile as “a hell that sustains itself by the strength of miracles, a withered hope that endures….” I think that this articulates how the impossible can survive through the strength of love. One trait that has marked theater in many countries, across decades, is its ability to survive against all odds, through the belief of those who make it.

In this way, in a world permeated by pandemic, full of uncertainties and dictatorships disguised as democracies, I call on us not to imagine theatres, but rather create and multiply them.

Theaters will be born in which we listen to and revive the language of our indigenous peoples. On the other side of the mountain, theaters will be born that tell the story of our ancestors who were not heroes. In a series of lost islands in the sea, amateur theaters will be born — those of neighborhoods, of migrant communities, of survivors of all the possible battles of this journey called life.

The theater will once again be a place of meeting and reflection not only for the elites but for everyone. This is the history that I want to be part of, together with my son.

I dare to invite everyone to this post-pandemic reconstruction. Let theater be the place of these small stories, a place guided by the words: Love, Respect, and Community.

Dedicated to Frie Leysen.

Translation by Alexandra Ripp.

About the Author

Language/Generations

I was at Weiwuying, the National Kaohsiung Center for the Arts in Taiwan this past December. I had been invited to attend a conference on arts participation and lead a workshop on festival curation. I’d been to Kaohsiung many times to visit family, but it was my first time there in a professional capacity. Everything was familiar and unfamiliar at the same time: I recognized the humidity, the smells, the tempo of this southern port city, but I was still a stranger.

In between conference sessions, I arranged to see a matinee. As my liaison handed me a ticket, she warned me that I likely would not understand it because it was in Taiwanese Hokkien, not Mandarin. The piece was inspired by the history and site of Weiwuying, built on former army barracks. It featured a genial narrator, a popular aging folk singer, Chinese opera, jokes about a local chain-store, beautifully shot city vignettes. It was a love letter to the city. I understood half of the language and references, but recognized the humor and the people. I felt strangely, and wonderfully, at home. I realized I’ve only experienced Hokkien around a dining table, not as live performance. It was a performative language full of inside jokes, loan words, specific rhythms — a linguistic dance I was more aware of perhaps because of my distance from it. For the first time in years I wished I hadn’t lost the language.

I wondered, how would this show do in festivals? How to translate it, would it translate? And I caught myself. The piece was made to resist being read easily by an outsider, and I had reflexively tried to package it for international consumption. Artists don’t necessarily make their work to tour; they tour if the economics of the making necessitate it. Not every piece is for a touring circuit, asshole.

My parents immigrated from Taiwan to Singapore a few years before I was born, in the 1970s. Growing up, there were different languages spoken at home: a mix of English and Mandarin with my sisters, Mandarin with my parents, and halting Taiwanese Hokkien with my relatives and grandparents. Japanese was also in my home — the remnant of the colonization of Formosa, but also from my parents’ genuine connection with the culture.

In homes and public spaces, Singaporeans speak Malay, Tamil, Mandarin (and the dialects Teochew, Cantonese, Hokkien, Hakka, etc.), Peranakan Malay, Hindi, Singlish, and more. English is the (dominant) working language of the state. Malay is the indigenous, official language of the country. Children are educated in English and take lessons in their “Mother Tongue” (Malay, Tamil, Mandarin) as a Second Language. In the race from “third world to first,” the government (like others) pressed on with regulation and standardization, privileging certain languages over others in the name of progress: English instead of “Mother Tongue,” Mandarin instead of the dialects, and so on.

Language can be lost in one generation — I worry about that every day with my young daughter speaking Mandarin. What, then, to make of the dialects that are spoken less with each successive generation, the very dialects that have drowned out indigenous voices? The globalization/colonization of cities presses languages out of cultures and out of the land. The globalization of culture presses art/works into particular aesthetics and a linguistic framework that is legible and translatable. If I had to imagine a theatre, it would be a theatre that resists with all its might being easily read, that flourishes in moments that are impossible to translate.

About the Author

-

In imagining a new theatre, my thoughts emerged as part curatorial dream statement, part personal manifesto, and part utopian fantasy:

I strive for a frame of curation where leading innovators working in time-based forms are given the same time, focus, and depth of historical and contemporary analysis that leading visual artists are regularly accorded by museums and by academia. In this world, the most challenging, opaque, and/or idiosyncratic performance work would get the kind of technical and financial support that mass-appeal entertainers receive without question. Multiple, ever-evolving contextual portals would be created in direct relationship with artistic production, attracting a wide range of audiences rewarded with deeper meaning and more profound experiences. Every project would involve extensive documentation, interpretation, scholarship, and archival strategies embedded from the start. The remaining institutional doors that limit artists’ access by geography, race, gender, discipline, or physical ability would be blown apart. Fellow national curators (myself included) would recognize when our own limitations of history/age/privilege were a barrier and step aside to let others more aligned with an artist or project take over. In this landscape, talented younger artists and curators would receive effective, thoughtful mentorship and training, while those more seasoned would acknowledge and draw inspiration from the energy and ideas of next-generation curators.

In my own curatorial practice, I’d finally achieve that perfect balance of offering deep support and rigorous critical response to the artists I work with, while also effectively translating their work to others, sparking intense curiosity and a shared passion about their creative work within a broad range of institutional stakeholders and regular citizens. I personally would aim for a more radical humility, where curatorial ego is dismantled (or at least diminished) and the power imbalance between artist and curator/institution is acknowledged and actively resisted. I’d better embrace personal dualities as well — bold yet modest, self-critical yet confident, impassioned yet studied, transcendent and epistemic, strategic yet conceptually daring. My practice would always be grounded in the etymological root of “care” in curation, nurturing living artists in their efforts to reinvent disciplines, combine forms, shift the dialogue, reanimate the public and take their place among the most important forces in this new society.

In this imaginary, utopic world, accomplished artists would be able to depend on systemic support for a lifetime of creative work rather than needing to constantly start afresh, attempting to make strong work amidst gnawing insecurity and financial instability. Binaries would be fully embraced — global and local; populist and esoteric; intimate and spectacular; conceptual and straightforward; academic and entrepreneurial; formalist and socially relevant; mysterious and highly rational; abstract and concrete; deep and broad. Artistic production and distribution would respond seriously to the vast climate and associated environmental crises, within which we seem to sleepwalk in denial. Artists and their curators/producers would help lead an essential societal transformation, inspiring other fields, rather than lagging behind, even if it means reimagining the energy-depleting movement of companies and productions, so long at the core to our fields. The artistic work of this imagined future, the ways of its making and the broader arts ecology, will offer solutions to how a surviving planet can transcend the treacherous politics we see today, addressing not just a non-carbon future, but also issues of racial justice and economic inequity. The philosophical, ephemeral, and at times improvisatory nature of live performance will offer essential structural lessons not just for arts but for how we sanely, and intuitively, devise rewarding individual and collective lives. Operating with fearlessness and joy, this artist-centered curatorial world would draw sustenance from the power of collective time-based artistic experiences, from the freedom and innovation offered by the artists of our time and of the future.

About the Author

“If the good doctor can’t cure you, find the less good doctor.”

— Tswana Proverb- In November 2015, internationally acclaimed South African artist William Kentridge gave a lecture entitled “Peripheral Thinking” at Yale University. In his talk, he raised the question of what is happening at the edges and how we can learn from it. He discussed the porousness of focus and described the ways in which studio processes can be instructive for looking at universal questions.

- In January 2016, I received a call at home in Johannesburg from Kentridge’s studio with a request to meet William for tea later that week. I had no idea what the meeting was about but remember waking up on the day of the meeting with a combination of curiosity and excitement. Later that day, I met a relaxed William just post his end-of-year holiday. He described a want to create and support a new space for the arts in Johannesburg. As a fellow artist, activist, and resident of downtown Joburg, he asked me to work alongside him and his studio team in initiating this space. The meeting was not very long, but I left it with formative words ringing in my ears: “interdisciplinary,”incubating,” “collaborative,” “collective,” “responsive,” “embodied.”

- In November 2016, I was in the eye of a magnificent storm of contemporary production.It was day three of an intense and massively generative five day incubator workshop working towards the inaugural performance season for The Centre for the Less Good Idea, due to open April 2017. Around 80 artists¹ from every discipline were being collectively curated by a five person team assembled by the Centre: a visual artist/filmmaker; theatre-maker/writer; poet/performer; choreographer/dancer; and composer/musician. We sought new combinations of text, movement, sounds and image. As we tested first ideas we hit upon incidental discoveries and had the opportunity to not only collectively identify and test them through repetition but to also capture the process, through film, sound, image and writing, an act of archiving fluid processes. The space was giving all its attention and resources to the impulses, connections, and revelations collectively identified by the artists.

- It was 4pm, and perhaps due to a late afternoon sugar low coupled with an unparalleled exhilaration, I had a sense of being outside of my body, a deja vu type of dream feeling — everything had slowed down, and I looked around the room: a group of poets and percussionists were responding by building sound and words to professional boxers in a boxing ring. A cinematographer and lighting designer were debating the best way to capture a visual artist furiously throwing clay and moulding it on to a dancer. An 11-man a cappella choir was moving in unison while a choreographer and operatic singer disrupted and responded to them. This was utopia, a safe making space for creative playfulness, and I was its animateur.Such a space doesn’t require a director in the traditional understanding of the word;it requires someone committed to maintaining energy and momentum, taking care of and holding artists in their processes, and pulling on threads and activating networks near and far.

- It is June 2020. The Centre for the Less Good Idea continues to be built in the same way one builds an artwork — through trial and error, piece by piece, allowing that which works to grow legs and letting that which does not fall away. If we had a manifesto it would be:²

- Sitting in the heart of downtown Johannesburg (a city famous for its violence and perpetual collapse),small and on the edge of the international art world is an incubator space for the performative arts. As founder and funder, William has allowed for an idyllic disregard for the usual economic logics of profit and gain which underpin so much art-making across the world. The collaborative collective approaches have, to date, given 400-odd artists over seven seasons and more than 30 one off performances an unparalleled momentum.

- So, what is next? We think, perhaps, an academy for the Less Good Idea?

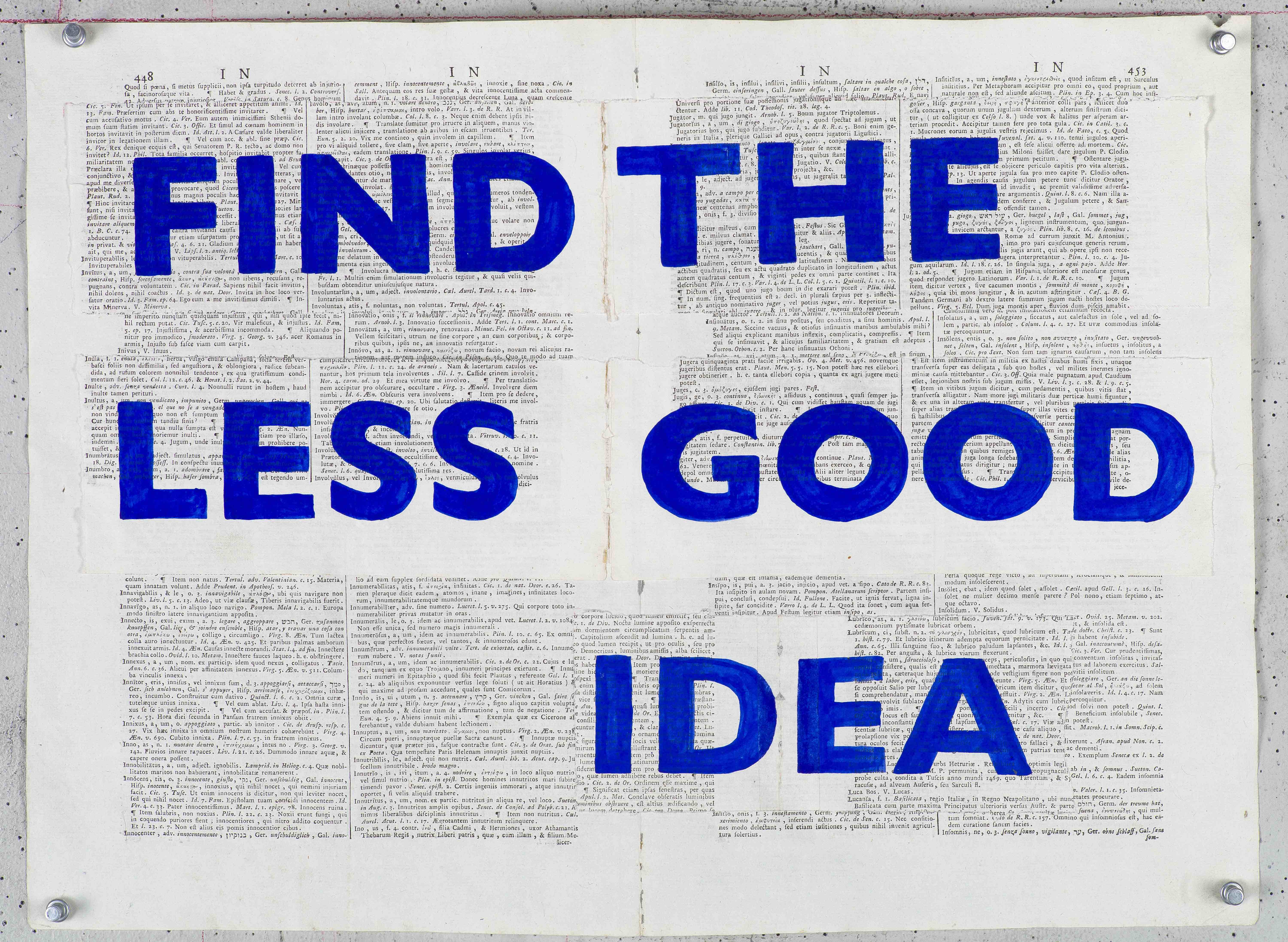

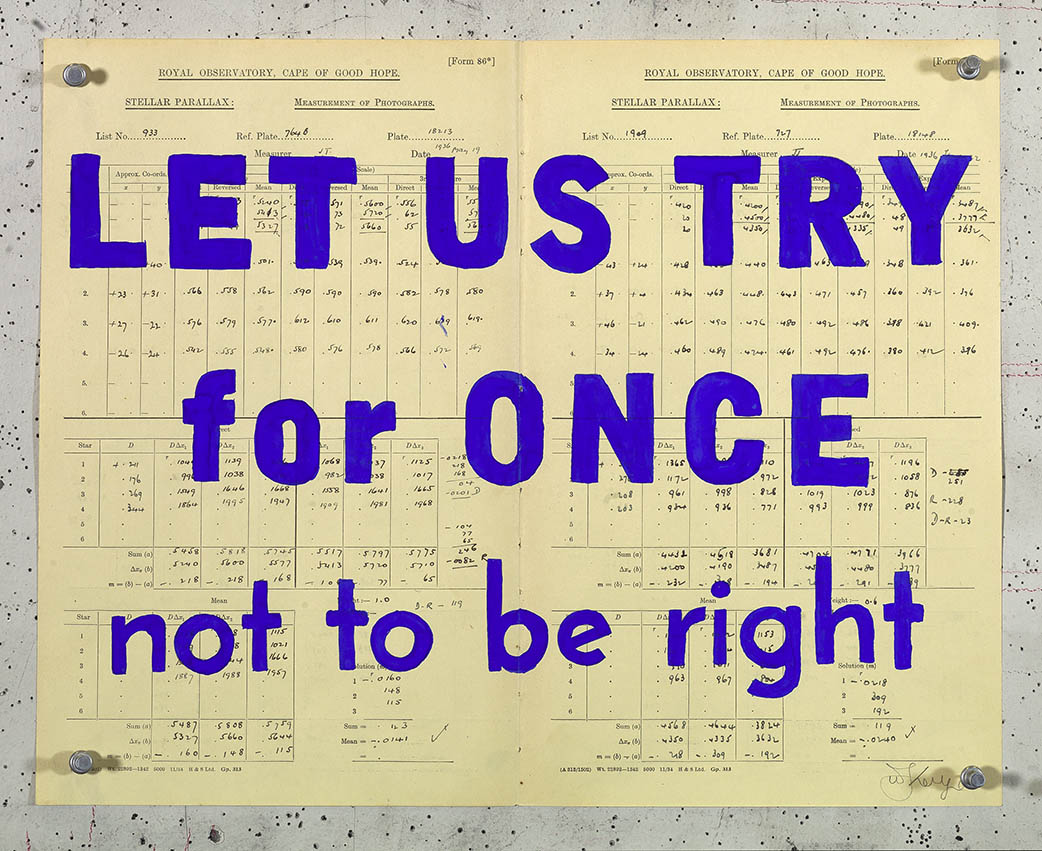

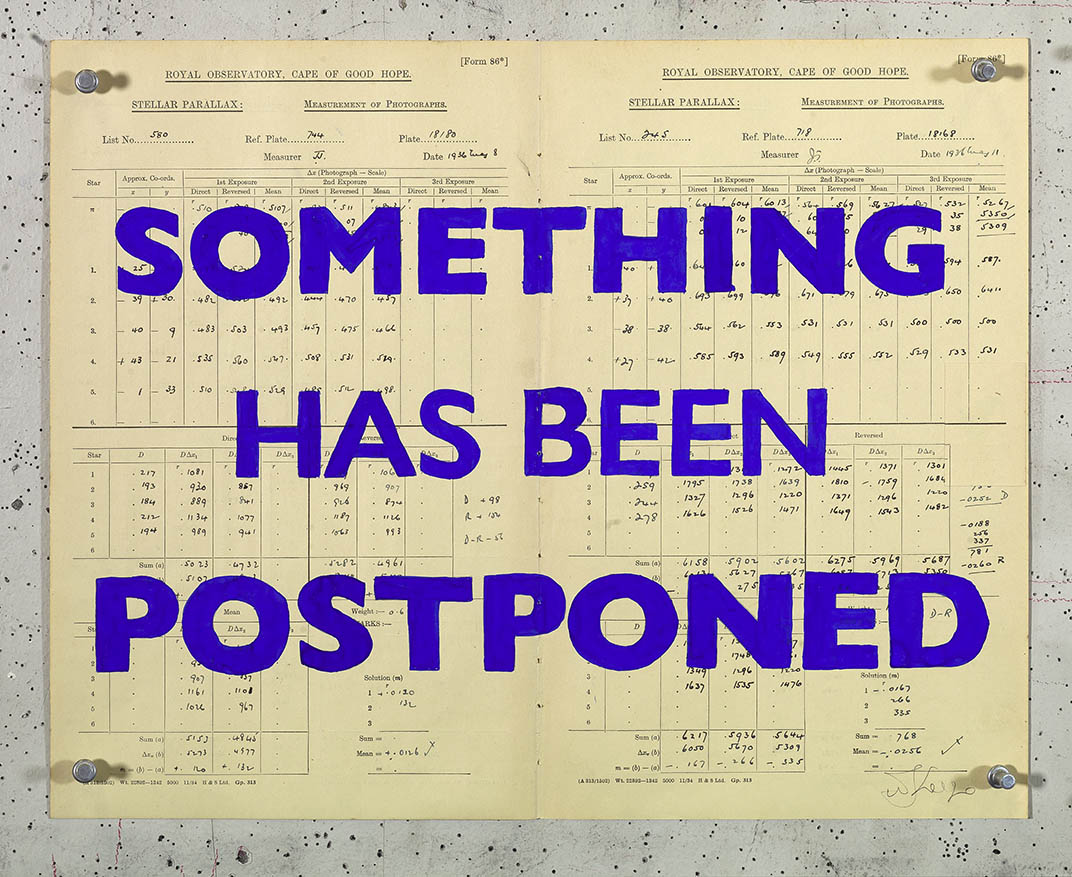

Photo credits: William Kentridge, Blue Rubrics, Lapis Lazuli pigment printed in blue on found thesaurus page.

1. The Centre creates two, six-month seasons a year. Core-curators from South Africa and of varying artistic disciplines are invited. The curators then engage practitioners with whom they would like to collaborate, and with that, the seasons grow. Alongside the seasons, the Centre has a monthly programme in which new work is incubated and shown for one night only. In 2020, we launched SO, the Academy for the Less Good Idea.

2. The Centre’s visual and conceptual identities are drawn from William’s practice, in particular his methodological approach to generating new large-scale performance work. Visually, our identity is based on his Blue Rubrics, a series William began after receiving a gift of pure lapis lazuli gouache from Afghanistan. In order to find a use for the vivid blue pigment, he addressed it in terms of its specific color and material. eventually mixing it into ink to overlay silkscreen prints. In William’s words, “They are called Blue Rubrics, but a rubric really should be red — a rubric was the printed or illuminated red text in a liturgical manuscript, in which the black ink would have been the text of the liturgy and the red would have been instructions on how to pray. So they are footnotes to a thought, the edges of the thought. In my case, they are unsolved riddles, phrases which hover at the edge of making sense… WHO NEEDS WORDS (the whispering in the leaves)…. These are fragments of sentences which sit in a drawer of phrases used in other work over the years, which get taken out and sorted through on occasions.”

About the Author

-

The word magazine comes from the Arabic makhzan, meaning storehouse: a place for materials to be placed and held, temporarily or permanently.[1] A magazine is a container, a vessel, a holding site–always with an implied temporal function. A magazine houses various kinds of materials or many specimens of the same type. A storehouse serves as a source: it is a repository and a supplier.

Like a building, a published magazine organizes deposits and extractions. In a cycle each serial edition replaces the previous one, supplanting it, yet advancing because of what came before. “To publish a magazine is to enter into a heightened relationship with the present moment,” writes Gwen Allen in her history of artist publications; magazines reflect their moment while also defining and shaping it.[2] Having captured the “contemporary” in serial, they also store these moments durably: in print, in archives, in annals, in volumes. Magazines imagine futures but in that future they also document the present as histories. They are ephemeral and disposable, but also archives, back lists, long tails.

For artists—literary, visual, performance—magazines have proven to be necessary, even essential, spaces since modernism. The pages of art magazines offer places for play, for experiment, for the formation of identities, stances, looks, ideas– foreshadowing key historical developments in the avant-garde and, indeed, making them possible by letting artists express on paper what they could not (yet) realize in other forms: think of Dada (1917-21), Cabaret Voltaire (1916), La Revolution Surrealiste (1924-29), the many magazines of Fluxus, and more recently Triple Canopy, e-flux, Raqs Media Collective, Sarai Reader 9. Artist magazines precipitate an altered future.

Goethe, the ur-dramaturg, said a magazine is like a series of rooms, a crossing of thresholds. Explaining the name of his Propylaen (one of the first artist magazines, 1798-1800), Goethe called it “the step, the door, the entrance, the antechamber, the space between the inner and the outer, the sacred and the profane; this is the place we choose as the meeting-ground for exchanges with our friends.”[3]

In the spirit of Goethe’s threshold gathering of friends, I propose a living magazine—The Storehouse—as a serial time-based event. (Storehouse #1, #2, etc.) Each edition lasts for a long weekend, taking place in one building holding a mix of forms. The public wanders through a collection of rooms, each with a different performance, exhibit, reading, meeting, game, discussion. Their experience is not fixed. They wander without moorings, the way a curious reader meanders through the pages of a magazine, not knowing what they’re searching for. Each edition convenes authors, sculptors, theatermakers, and explores an urgent question of the day—what defines illiberalism? How does color define perception? What is anonymity in 2020?

In one room, three philosophers engage in spirited debate and invite visitors to join them at the table. In the next, a photographer’s display. Then a hall inhabited by dancers in motion. An immersive theatrical installation. And so on. The order of encounters is determined by the visitor’s curiosity. The participating artists and writers get to see what the others have contributed to the overall investigation. Everyone is surprised by the collisions, disarmed by unexpected encounters.

Could a sustained platform of this kind serve as a model for the current tidal wave of nonobjective art experiences, grounding cultural communities in a shared sense of critical values and inquiry—missing since the 1980s? Could the dimensions of a live immersive “publication” encourage public-facing artists, leaving a trail for those who come after? Momentary heat from the convening gets captured in print or web publication. Would a built-to-dissolve edifice serve as a (much-needed) invitation to play, with low stakes as part of a community of other writers and makers?

What if this live discovery platform encouraged shared thinking-through of political crises and aesthetic impulses? Could we affirm the importance of collective creativity by coming together in regular cycles? What if this was a space for spontaneity, not careerism? How could the loose experience of discovering contents in “magazine” form yield a new component of liveness: live readings, shared spectatorship, collective response?

In his essay “On the Grammar of the Space,” Boris Groys writes: “Today’s art space can be regarded as beautiful only if it is rhetorically persuasive.” In the Storehouse, inquiry happens on your feet and the art space holds bountiful supplies. The collectivity is beautiful; it persuades.

[1] See Gwen Allen, “Magazines in and as Art” in Documents of Contemporary Art: The Magazine, edited by Gwen Allen. London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2016. 12-13.

[2] Gwen Allen, Artists’ Magazines: An Alternative Space for Art. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: MIT Press, 2011. 1.

[3] Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, “Introduction to the Propyläen” (1798), quoted in Allen, Artists’ Magazines, 3.

About the Author

Disarmed by Unexpected Encounters

As we count the days back to the possible point of exposure and forwards to the remaining time of isolation, as the everyday loses all spontaneity of unexpected encounters in the endless repetition of routine, engagement with others seems to be the only means of capturing the present, of challenging our own single-perspective notions in the face of a multitude of often uncomfortable polemics.

In a similar way, we’ve frequently been caught in the performance machine of spectatorship in the theater, seeking indices and our own routes into the performance, into the environment it establishes, seeking an aperture, an opening leading to a being-here. The theater we yearn for is not an “alternative” to the “real” world but is a “real place, where real people go to work, and where their work takes the form of ‘conversation.'”[1] There is no single perfect vantage point, but rather a series of possible entries into the event. Narrative continuity is extremely unstable in these circumstances, with dramaturgy constructed by chance encounters with others, by failed gestures that remain in traces, by the unplanned. We design a space of friction, a happening, a multitude of conversations.

After our performances, the public joins us: touching the props, examining the abandoned costumes, testing the floor, and looking back over their shoulders towards the now-empty seats. The performance is over, and an excavation of sorts begins. The gaze turns its object, the theatrical event, inside out, looking at its seams: the duct-taped cables, the backs of screens, the lost sock, the stage lit up by working lights, devoid of shadow play.

Like the people in Brecht’s Street Scene, we are stuck on a street corner, struck by our responsibility for the event. As the dust settles, as the sweat is wiped away, we find ourselves in an encounter with memory and the traces of the event: among the material and cerebral detritus, among the fascinating ruins. What is left on stage takes the shape of a strange post-festum instruction manual or informational guide. This exploded view of traces and ephemera functions as an extension of the performance itself and is more reminiscent of a situation in the making than one that has just passed.

BADco. is a collaborative performance collective based in Zagreb, Croatia. Since 2013, we’ve initiated a series of 24-hour events,[2] inviting others to join us in temporarily inhabiting spaces—ecologically problematic urban zones, former industrial buildings, abandoned construction sites of cultural venues. A day would start with setting up tents, a generator, cables and mics, parking bikes and letting dogs run around, coffee—but also a segment of choreography, a reading, a workshop, an interview. And it would continue with conversations, concerts, objects, dance.

Even if we planned a schedule or a narrative arc, performing in such a setting inevitably leads to text spoken or choreography danced coming into proximity, into correspondence with what others brought to our expanded conversation, leaving us disarmed by unexpected encounters, creating a space of friction, a space—to quote Congolese choreographer Faustin Linyekula—”where a work of art and the spectator come together to produce a crisis, as well as mutual recognition.”[3]

[1] Nicholas Ridout, Passionate Amateurs: Theatre, Communism, and Love (University of Michigan Press, 2013), 124.

[2] More on the project at: http://badco.hr/en/work/1/all#!nature-needs-to-be-constructed

[3] Florian Malzacher, Not Just a Mirror. Looking for the Political Theatre of Today: Performing Urgency 1 (Alexander Verlag Berlin, 2015).

About the Author

-

Optional reading soundtrack: “SYM” by Kano (Hoodies All Summer, 2019). “SYM” (Suck Your Mum) is the closing track from British Grime-pioneer Kano’s sixth and latest album release Hoodies All Summer. On Friday November 8, 2019, Kano took to the stage to perform “SYM” live on Later… with Jools Holland, which was broadcast on BBC Two.

When I listen to the final track on Hoodies All Summer, I imagine myself sitting in between the ‘Sunday Best’ piano accompaniment pulling me into the pews of the church of Grime, and the choir of gospel singers bobbing side to side like bottles in an ocean, harmonizing one of the finest cusses with finesse – “Suck your mum.” At the altar, I see Kano and his perfectly-fitted suit, standing in all his vindication and protest and beaming at the worn-out congregation while wearing a contagious smirk across his face that tells us he’s tired too, and he sings, “Suck your mother and dad.”

This is a non-negotiable call-and-response to all of Britain’s terrors, and an ode on behalf of all of the children of the empire. ‘SYM’ feels like the Harvest of Sunday’s church; the one integral service that knits together all elements of lost faith, making you remember what it felt like to believe in something wholeheartedly and wanting to spread the good word unto others, or the one scripture you come back to because it’s the only one you know off by heart, or the prayer you turn to when the rock and the hard place form an allyship.

From Pardners and Windrush to the school-to-prison pipeline and slavery, Kano builds a climax of “fuck you’s” to the legacy of British colonial ruling, and when we sway with him, we sway in solidarity, in understanding, in equal and justified anger and acrimony and fire and burning and burning and burning. The people that sit on the rooftops of anti-Blackness, the ones that have been dancing on the graves of Black bodies for generations, sway with us at the beginning. And then they stop. How betrayed they must feel to bop to the beat of this severe beating down; how hurt they must feel that this is to them and not for them, even though they consider themselves the anomaly. Even though they’re the good ones. This, at its core, is theatre at its finest. These onion-shaped stories that unpeel themselves to reveal layers of conflict and secret languages and joy only a couple of people will understand. This is what I consider to be the bricks and mortar of theatre that Black communities across the diaspora have created for centuries.

My Imagined Theatre is one that acts as an accountability partner—one that speaks truth to hardship and authenticity to bullshit on any podium or soapbox that can be made with what we have and with no permission needed from ‘The Man’ and his son. This doesn’t mean stripping the art of its entertainment values—I’m sure the plenty of people gleefully singing “suck your mother and dad” at the top of their lungs were having a grand old time before reaching for the second line and wiping the nervous sweat from the top of their foreheads. Those are the moments I live for; the duality of theatre.

If this is my understanding of theatre, then it is impossible for theatre to exist within the binaries of institution-led kudos and structures. If I am to think of what I know theatre to be, I can map this evolution in the oral traditions, musical translations, and poetic tellings of my ancestors, and perhaps the purpose of my Imagined Theatre is to come back to the source; back to where we started and where those before me have already stood. Binding performance to stages with proscenium arches or large auditoriums with tiered seating is the inevitable death of theatre, and the lackluster thinking that something as radically expressive as theatre could be whittled down to the boundaries of white institutionalism is not only a mockery of the legacy of performance Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities have embodied for millennia across the globe, but also an undermining of how much these communities have done, can do, and will continue to do outside of the institutional definition of ‘culture.’

When reimagining the framing of theatre, particularly within the context of Blackness across the diaspora, I think of the oral, musical, and movement-based rituals of performance that have been handed down over generations. Not all of these forms and performances exist for everyone. There are codes, secret alleyways, and hidden dialects that speak directly to the few about the many; about modes of survival; about translating our documentation for future generations; about what it means to be our full selves, all day, every day. The Imagined Theatre that exists in this world isn’t one that blindly and untruthfully pretends to speak in a non-existent universal language, but rather implicitly states in its ethos that language is to be shared and spoken genuinely and with legitimacy, and those who are meant to hear it, will.

To be able to imagine should hold a power of freedom beyond expectation and present realities. Instead, the imagination has been capitalised as a bartering tool to dictate who defines culture and who culture belongs to—who is allowed to imagine and have those imaginings exist without being gaslit, undervalued, and undercut. Despite this, what I continue to learn is that Black cultures—in all their hues, impacts, and differences—carry the art and life of performance and theatre in their bones, and Kano teaches me that the Imagined Theatre I wish to form holds true and fearless work that comes from the freedom and validity of the imagination, ourselves, and our communities.

So, if I want to tell Britain to “Suck Your Mum,” I can. And I will.

About the Author

Optional reading soundtrack: ‘Nina’ by Electric Fields (Inma, 2016)

What’s free to me? It’s just a feeling. It’s just a feeling. It’s like how do you tell somebody how it feels to be in love? How are you going to tell anybody who has not been in love how it feels to be in love? You cannot do it to save your life. You can describe things, but you can’t tell them. But you know it when it happens. That’s what I mean by free. I’ve had a couple times on stage when I really felt free and that’s something else. That’s really something else! I’ll tell you what freedom is to me: NO FEAR! I mean really, no fear. If I could have that half of my life. No fear! Lots of children have no fear. That’s the only way I can describe it. That’s not all of it, but it’s something to really, really feel. Like a new way of seeing. Like a new way of seeing something.

– Nina Simone (1968)

I first heard these words—spoken by the legendary American singer Nina Simone in a 1968 interview—not from their primary source, but sung as the lyrics in a 2016 song—Nina—by the Australian electronic/pop band Electric Fields. Helmed by Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara singer Zaachariaha Fielding, Electric Fields have lit up the Australian music scene with their fusion of shimmering, melodic pop, and invocations of Australian First Nations cultural stories, strength, and sovereignty. Their music sparks with an energy that transposes the vast and complex histories of Australia’s First Peoples into euphoric, reflective moments that infuse the dancing bodies for whom they perform and play. I heard them for the first time at a queer dance party in Sydney.

Nina Simone’s words, inseparable from her lifelong struggle as a civil rights advocate, reverberate powerfully with the different definitions of “freedom” that might be considered by Black and white people in a contemporary colonial world. Freedom from the kind of fear that emanates from the violence and oppression of white, patriarchal institutions. The fear that seeps from government policies and corporate power structures directly into people’s bodies, memories, and hearts. What would it mean to be free of such fear? What would that feel like? What would it enable? I’m not African American or Indigenous Australian, but I’m a queer man of color, and I think that’s what I go to those parties for: to find out what that might feel like.

Recasting of Nina Simone’s words to Electric Fields’ melodies reignites a flame of conversation that not only touches on the civil rights movements of the 1960s and present-day struggles for First Nations sovereignty, but that stretches backwards and forwards through time and considers the battles of all racially oppressed peoples to find sovereign self-expression in the face of a monolithic and opposing cultural power. Perhaps this Imagined Theatre is the one that keeps that flame bright and strong, across generations, borders, cultures, and barriers. Perhaps it’s this Theatre that might finally fan that flame into a firestorm, strong and fierce and pure enough to burn down those old outmoded ideas of race and the power structures they serve. Let them fall away. And there we will be, dancing in the ashes.

About the Author

-

A series of questions by Silvia Bottiroli and Low Kee Hong

Why and what has led us to where we are now? Our world is in a state of crisis — a crisis of our generation, of our time, and of our own doing. In our day-to-day, we have to face the many oppressions brought about by these many crises — within ourselves, in our domestic situation, our national condition, international geopolitical and global ecological malaise. We are dealing with a broken world that seems almost beyond repair. What then does the future hold? Is there a future to behold?

In the last two years, we have lived through, and are still reeling from, many difficult moments in many cities around the world. Right now, we are confronting a reality that we thought unimaginable, that is shocking to us, that has required us to rethink and abandon the many assumptions we have about the structures and institutions that have such deep implications to our everyday lives. And so, where do we go from here?

For the arts and for theatre, it is not time to continue working as usual, in ways that have definitely proven their unsustainability. However, it is also not time to give up, but instead to rethink, reshape, find, or invent other forms and ways to continue. How can we then rehearse practices of life, of collaboration, of work, and of art that can operate despite the current state of things? How can we exercise to exist and produce meanings, regardless of all contingencies and limitations? How can we keep insisting?

What if the theatre is just a space of rehearsal, a space to rehearse a world to come? What if we do not have an image yet of what that world will look like? What if we can only rehearse it together, across and beyond our differences? What does the specific apparatus of the theatre have to offer to us in this rehearsal?

What if we define values, principles, and methodologies, resisting the pressure to define outcomes? What if we focus on what drives us and on how we want to live and work together, but leave the imagination open to the concrete shapes our collaboration can take? Shall we end up producing different art forms and curatorial concepts than those we are already producing? And different with respect to what exactly? What could be the value of this difference?

And how can we make time, when there is no time? How can we make focus, within furious circumstances? What words do we need?

How can we propose a new lexicon, re-appropriate and re-signify existing words, translate them into numerous languages, invite others to jump in the process, use and misuse these words, make other sentences with them?

If we take co-creation and co-authorship seriously, as constitutive components of how we live and work, what does the horizon of our making become? What if, in other words, it is not about us, not about our project, but rather about the conditions it provides for something and for some other things to happen? What if, all we aim to produce are feedback loops?

But also, what if we could collectively float above the current storm?

About the Authors

A response that has everything and nothing to do with making performance

Can you hear me?My quarantine partner, my husband, is a white man. He tells me he does not know if white people know how to suffer or sacrifice collectively.My phone buzzes with messages and DMs from white friends, colleagues, and acquaintances I rarely speak to.“Just checking in”“How are you?”“I love you”“I am sorry this is happening”“As a white woman, what can I do?”I knew then that I would have to stop talking to white people. As in, I need to stop intentionally talking to white people for a month.At least for a while.Why were they calling me now?This is not the first time a Black person has been viciously murdered by police. This is not the first time Black people have taken to the streets, demanding justice. But now my phone was crowded with casual declarations of love and long apologies from well meaning white folks.In our quarantine bubble, stocked with rice and beans, too much pasta, and copious amounts of red wine, we improvise a sense of safety. Our jobs moved from the outside world to the comforts of our home in Oklahoma City, and we know we are privileged, to be home, to be working. I roll up the rug in my living room, prop my laptop on a pile of books and blast “Panama Mwen Tonbe” (an old Haitian folk song) loud enough for my students to hear over Zoom. Swinging my arms outward, I demonstrate spins and footwork while dodging my cat Jack at every turn. I get accustomed to being in Zooms and fumbling with the mute icon as we ask each other,“Can you hear me?”The other part of my career that relies on performing artists coming together and creating something in real-time, that relies on audiences sharing the same space, that relies on that energy which follows us from the show and spills into the bar down the street –that is gone. Perhaps momentarily, but it’s been swept up as a casualty of a non-discerning pandemic.Even so, there’s no time to mourn that loss, because thousands of people are dying every day from this virus, and without so much as a dirge, the Second Lines in New Orleans are forced into silence when they are needed most. My NY Times alert says Black people and native people in the US are dying at a shockingly disproportionate rate; there were dozens of decomposing bodies found in unrefrigerated trucks outside of a Brooklyn funeral home.What the actual fuck?!!I retreat deeper into the bubble. My body seeking out the Second Lines that are too quiet.It’s Saturday night; 90s dancehall legends Beanie Man and Bounty Killer are battling live on Instagram series Verzuz. I run through the house doing the bogle, leaning all the way back, fingers gliding through the air, slicing through the patois. My body is alive and vibrating. I am transported to the crowded basement parties of my youth in Queens, NY, back when our sweaty bodies were allowed to touch, before we knew Beanie and Bounty would become our problematic faves.What has changed?

I retreat to the Black women artists, educators, elders, mamas, and organizers in my life, and we discuss, we leave moments for quiet, we let our anger unfurl, we write, we meditate, we dance, we hold space for others, we strategize for a future that includes us at the center.

In the morning, I water my tomatoes and later watch my friends live-stream their performances from home. I check in on my producing partners to make sure they are applying for unemployment.

They are.

I check in on my family; they are mostly fine, except my brother, his new wife, and six-month-old baby all have COVID, and it’s bad.

My sister makes a family group chat for daily health checks, and it’s quickly populated by the aunties with herbal COVID remedies and inspirational quotes superimposed on roses.I don’t mind.

We are going to need all of the aunties and their inspirational quotes.We’re trying to survive a pandemic

in the midst of a racist epidemic,

and now an uprising, 400 years in the making.Are you ready to improvise without me showing you the footwork?Are you ready to sacrifice without my body on the line?Are you willing to create a new tongue, so that we may collectively speak and live freely?Edited by Haydee Souffrant

About the Author

-

Were I to imagine an ideal theatre (which is not, I understand, the proposal – and I’m not about to do it here – but it does beg the question, from the get-go: why imagine anything that is not somehow “ideal”?), I think of moments of cultural impact that were better, I expect, to hear about than to experience, like Woodstock or the Geneva Conventions. I imagine a theatre that can be talked about – and in the telling, amplified. Spend much time around “theatre people” and you’ll discover that this is not, in practice, an unusual occurrence. “Let’s not, and say we did” is our mantra. I exaggerate to make a point.

Let’s talk instead about the theatre that does exist, and must exist.

The theatre that must exist is ugly and unsatisfying, much of the time. It is defined by failed efforts and a bizarre-bordering-on-pathological determination to return to the scene of the crime (in this scenario, artists are the criminals; art is the bullet; guess who the victims are?). Thankfully, funding being what it is in these United States, the gun is rarely loaded.

I know, I sound like Dostoyevsky.

The theatre that must exist, and does exist, is not unlike a visit to the dentist or the DMV. It’s tedious. It requires effort, from the maker and the viewer alike. It tracks the mundane passage of our daily lives, like the weather report. I love this theatre with every ounce of love I have to give, because occasionally – occasionally – it transcends anything I could have possibly imagined for the world. Which is why I prefer not to imagine it at all. I’d rather show up and wait, knowing that something of significance will happen, even if it takes a while.

There’s nothing ideal about it. But it matters. It matters.

My title is “Artistic Director” – a meaningless term, on its face. I do not possess a “curatorial” mind, though I do make choices that lend a certain shape to things, over time. If the theatre that must exist, and does exist, is a sweatshop – and it is – then I’m the shop steward on the midnight shift. Nobody needs a curator on the factory floor. My job (if I can call it a job) is to respond, support, cajole, commiserate, and live among artists who sacrifice everything for a lost cause. We’re putting in the hours, all of us. There is no conscious thematic or contextual basis for anything I do. The work continues and the narrative writes itself. If we’re lucky, there are witnesses. It’s important to be witnessed.

I write this from my studio at the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire, which is in its way a kind of shrine to the agony (and, I suppose, ecstasy) of solitary effort. The theatre that must exist, and does exist, can be crushingly solitary in the making – and then, crucially, it explodes into something authentically communal. That is the theatre that I do not wish to imagine, but wish to have.

About the Author

The Time of the Now

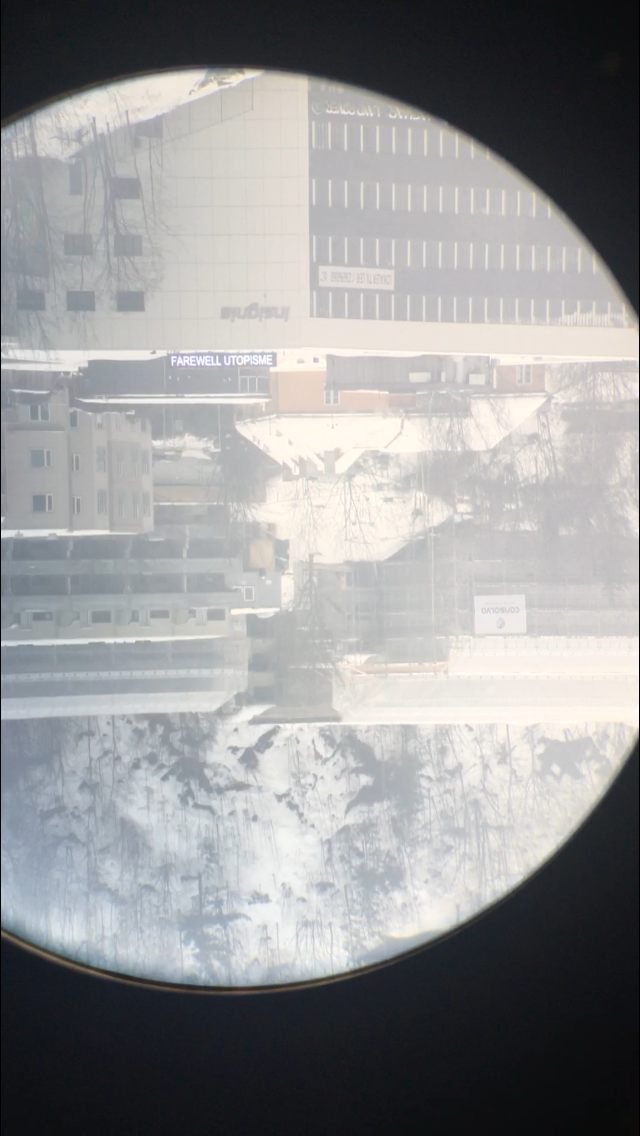

Dries Verhoeven, “Fare Thee Well!” (Oslo). Photo courtesy of the artist.

I am writing these lines after my first academic year at New York University in Abu Dhabi, one year after the last edition of Fast Forward, the site-specific festival that I imagined and curated for Athens as a critical response to the multifaceted “crisis” in Greece. I am writing these lines during a dematerialized summer shrunk to a disembodied liveliness and to a distanced sociality across space-times. While I am struggling to imagine a theatre that matters. As I always did. But now it seems that it needs to matter differently. It seems that it needs to address differently the urgencies that exist in the here-and-now, present but often latent, confined in between the anxieties of the creation time, the precarious conditions of the production system, the institutional imperatives, and the contested sponsorships. Does the fact that it needs to “matter differently” mean that we need to invent “new” forms and subject-matters? To challenge any exoticization through alienation? To decolonize originality and authenticity? To reconsider sustainability but also post-humanity? To privilege theatre as a social process instead of theatre as commodity? I honestly don’t know.

I am writing these lines as I need to imagine something in order to make it. Theatre is always, for me, a porous, relational common ground where discursive events go hand in hand with poetry and radical aesthetics. Theatre is a translocal space of togetherness, a collective state of mind where unimaginable forms of engagement and emancipation can potentially emerge. Theatre-as-commonality reminds us of the essential role that theatre has played in all times: from the ancient city-states to the struggles for freedom and justice in our “short century” and the ongoing fight for a world that matters — for all, equally.

I am writing these lines thinking that we need perhaps to unmake theatre in order to imagine it — to un-make means, Homi Bhabha writes, “to release from repression, and to reconstruct, reinscribe the elements of the known.”[1] Does that mean that theatre shall assume the responsibility for the unspoken? Shall we collectively envision cultural events that transcend the way that we have shaped our “global” art world? Could we rethink the role of the curator as a public servant at a moment when we don’t even know what “public” means? Is it possible to identify and dismantle the power relationships that shake the artistic field both on the inside and the outside? Shall we reconsider the distribution of resources beyond postcolonial concepts such as the Global South, or essentialist approaches to interculturalism? I honestly don’t know. I am only thinking that we need to re-imagine it.

[1] Homi Bhabha, “The World and the Home”, Social Text (1992, n. 31/32), 146.

About the Author

-

Imagine a sanctuary set in a clearing in the trees — not a theatre in the traditional sense of the word, but a place where people gather for music, dance, poetry, storytelling, speeches, and parties. There are performers and an audience, so to speak, but no script, sacred text, director, or minister.

The sanctuary is used for services led by members of the fellowship who take turns planning and performing. These vary greatly depending on who is leading them — youth and elders, newcomers and old-timers, believers and questioners. These performances draw on the personal, political, and universal. Sometimes there is a dance, a film, a call to action on a pressing social justice issue, a guest speaker, or a performance of a scripted play. The quality varies as much as the content because the members of the fellowship are amateurs in the most generous definition of the word — people who are lovers of something rather than experts or professionals who do something for money. That is not to say that their offering is something lesser than a “professional” one, but more like a home-cooked meal versus something from a restaurant.

Some of the members attend services for years and never take a turn leading or performing; they are what we might call the audience. They bring flowers, make the coffee, pass the collection plate. But most importantly, they show up, week after week, and give their time, attention, and open minds to whomever happens to be on stage. Sometimes the service is inspiring, beautiful, meaningful, surprising, enlightening, funny, thought-provoking, maybe even all of the above. But to be honest, many times, it is boring, off-key, derivative, embarrassing, awkward, preaching to the choir, or just not one’s cup of tea. The fellowship relies on a group of people who show up despite this, or maybe even because of it.

As a kid I was part of such a fellowship, a Unitarian church without a minister, and I often imagined an alternative version of that fellowship with “better” art. I find myself a part of something like that now, with artists working at a truly expert and professional level (even if they are not paid, or not paid enough.) The art is undoubtedly “better” in terms of quality, rigor, critique, diversity, equity, and craft, and the shows often feel like a kind of ceremony or service. I feel a special connection with others who create and show up for this kind of shared experience, and who travel the world to find it. But we are only together for a few hours or days here and there. What if we had more time and space to just be with each other in a more relaxed and ongoing way? What if artists could be supported to do what they love without the pressure to make money?

I imagined a more theatre-like fellowship as a kid; now I’m imagining a more fellowship-like theatre, with time and space to show up for each other as amateurs. Maybe there could even be a sanctuary for doing things that are not quite art or work, for taking turns leading services for each other. How fun to imagine all my favorite people together in that sanctuary.

About the Author

Photo from Burrard Inlet, courtesy of the author.

A Response from a Circle of Cedars

Dear Erin,

I read this essay as an articulation of your practices and as a call to act and manifest them into reality. I also read this writing as its own realization in the world; a story with generative power, developed in community through the telling.

I had these thoughts in mind as I sat in a gathering of cedar trees along the Burrard Inlet in Vancouver. Looking out at the water, with branches forming a kind of sanctuary above, I stared at the beauty of this northwest world. I remembered Musqueam weaver, artist, and knowledge keeper Debra Sparrow speaking of her grandfather Ed Sparrow who told her how the Musqueam people — whose villages had been in this inlet — were forcibly removed and their home burned to the ground. That home site was gone, but the power of story, passed down through generations and then shared, now shaped my understanding of where I was. Sitting there at the base of a tree, I held that cruelty, the peace of the trees, and the longevity of her family story in my thoughts. I felt like I was also becoming-tree; keeping witness.

In your writing, I imagined who was there, the easy respect given to each person bringing their creative involvement to surface, and how content we were to be in that place, ready to go wherever these expressive paths led. Your story is part of this doing.

Versions of this event surface in my mind: open mic at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe when that nervous 16-year-old girl heads up with her worn notebook, opens the page, and the whole room breathes together listening to the journey of her words; a Jeff Buckley concert in the early ‘90s at the Sin-e Cafe as he went in and under the emotions of the song to return us all into a wider universe; Montreal’s Studio 303 and Casa del Popolo as we danced and trained and sang our way into a community that is still in touch over 20 years later; a wondrous night at Bar 169 in downtown Manhattan with an open mic and a gathering ready to share it all THAT night, with an audience (and bartender) holding us close enough that we could let loose; improvised and gorgeously intimate performances of West African and Afro-Cuban dances disguised as Monday night intermediate classes at Lezly’s Dance & Skate School and Fareta just north of Houston on Broadway; Bruckner’s Bar & Grill in the early 2000s, Pregones and BAAD! Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance always — with our combined love of ALL things Boogie Down Bronx and what was shared in that mix; the dance community in Vancouver riding their bikes in the rain to give feedback at rehearsals, posting dreams about new work online, walking into any studio, sitting on the floor, ready to open their hearts —not saying no to themselves.

Your vision is a “keeping place” for refueling and inspiring fellowship in the world. It calls for relationships that sustain and hold and call more to happen.

Thank you for reminding me,

Jane

This work was written on the traditional, ancestral and unceded Coast Salish territory of the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) and xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) Nations. Thank you for allowing this uninvited guest to live on your land and enjoy these waters and abundant beauty.

About the Author

-

the time taken to memorize

the distance between yourself and the thing

change is only legible in relation:

use another genre

invite another idea into yours because of what it does

What happens when we imagine the edifice, those galleries, walkways, lobbies, and that state-of-the-art theater, no longer in its current use?

a set of influences (past, present)

a world within it that normalizes (and makes impressive) certain tropes or gimmicks

the subtext of “blackness as worse than the worst thing imaginable” in this sick fantasy

making the hatred clear but doing nothing about its putridness amongst the rubble

When going about business-as-usual loses its cohesion, but the building still stands?

looking for the scales to tip, looking for ways to draw the boundary

only write when you want to share a revelation, a moment of surprise, with other people

start with concept, then medium

rehearsal is all talk, get to the movement

decide what kinds of gaps need filling

When moss grows over it all and we have to choose to climb through the structure together, make it safe for children again?

welcome the audiences to share and move through the stage space

create the “illusion” of a performance in a dark theater

move out of it, ignore its usual uses

(categories are/as lineage)

Will it still be a useful place? (Do the speakers and lights still work? Can we crack a hole in the ceiling to let in more light?)

sharing rhythm creates a political question about who determines rhythm and when

trio in unison, with the possibility of becoming either backup dancers or soloists

open-ended and absurdist and nonsensical

shame as part of gaze

Will we let each performance make its mark — hack out part of a staircase here, paint that wall turquoise, bring our own furniture, put in shag carpet (or finally take it out)?

living death (we’ve gotten used to dying), living with it

care and the carceral

a solo aligned with therapy

dancer not as victim but as person

entering the stage after silence

Who will show up to use it after the signage and logos have fallen off? What will they believe about what being together to make or watch a performance requires?

ask them to reinvent some piece of the museum’s conditions

what has this artifact been conditioned to narrate?

breathing archive into the present

given enough time, sweat through to the past

ancestor work is trickster work

disorientation practices, habits and behaviors

pressure and traction, consonants and vowels

love notes

levitating, like baptism

who do we allow to think our problems out loud?

(we can’t fill in the imaginations of people for them)

Are these unreasonable questions?

how to put your pulse back up your sleeve

the difficulty that propels us to perform

What tenderness do their answers inspire toward the work to be done in the present, under — or because of — the circumstances?

perhaps we are past help

but where, exactly?

Note: The elements of this piece in italics were inspired by a conversation with artist C. Davida Ingram.

About the Author

Withness, without us

We had seasons, festivals, and tours, we had work days and evening performances and opening and wrap parties. If something fell off pace, it merely got left behind. See you next cycle, try to catch up. What happened once we all disappeared together?

The last performance I saw/managed before The Kitchen closed to the public was an open secret. The worst kept secret. Ralph Lemon staged the third iteration of his Rant performances as part of Okwui Okpokwasili and Judy Hussie-Taylor’s curated series for Danspace Project. It was a secret because the audience was meant to consciously be there. Someone wanted you there; maybe it was Ralph or another performer, maybe it was The Kitchen or Danspace. Kevin Beasley created the booming soundtrack through his own sound system that provided much more power than a small black box theater needs. Ralph, Okwui, and Samita Sinha’s voices reached over the beats. Dwayne Brown, Mariama Noguera-Devers, Stanley Gambucci, and Paul Hamilton danced in unison, and Darrell Jones stepped out from his seat in the audience for a solo. The air was humid with sweat, and the performance was followed by a lot of hugging. I was closing down the building so I let everyone linger afterwards for as long as they wanted. There was time, people didn’t feel in a rush that night. A few months later, Ralph wrote briefly on the work for MoMA’s website and lamented the luck of this occurring before we all scuttled into our apartments and hid away. Why was this particular, not quite public/not quite private performance blessed by timing, and not others? There is no trace of this performance on our website, where so much performance is now presented, because it was a secret. It was made to remain within our bodies. We didn’t know that many other future performances would be erased, but in another way, and would have to live on in our imaginary.

Rant is an iterative score filled with expressions of rage and freedom, created by Black and Brown artists in a dark space within an institution. There’s accumulation, but no peak. (Maybe it’s all peak.) I’m reading Tara’s score of performance notes as a gathering of past shared moments. We’ve fallen out of time for months now. If we can’t even remember what day it is, how can we share time? Conjuring the past has been such a comfort.

It can feel like it’s only grief and rage that bring us together now, not in the darkness of the black box, but in the hot summer sun and on our small screens that will contain us for a long while. We’ve been with ourselves for many months now. Without our routines, we can often feel like our bodies are these emptied theaters. We’re not useful. We’re not housing the senses and the other bodies that fill us up. But as Tara writes, “change is only legible in relation.” If it wasn’t clear before, universal grief doesn’t exist. Universal rage doesn’t exist. We’re beside ourselves right now. Togetherness needs to remain relative.

About the Author

-

Notes, inspirations, and ideas structured as a schedule to help reflect on the notion of time.

6:08AM

Set your alarm every morning at a different time.7:30AM

Read an essay.In the introduction of his essay Time, Capitalism, and Alienation: A Socio-Historical Inquiry into the Making of Modern Time, Jonathan Martineau argues: “We live in strange times, and we live in an estranged time. We order our lives according to an abstract, impersonal, and extremely precise temporal order, but the concrete experiences of our lived times often seem out of synch with the abstract character of our clock-based social time regime. It is as if our obsession with saving, measuring, and organizing time has gone hand in hand with our own temporal alienation.”

8:38AM

Don’t click here.

You might lose your time.9:00AM

Think.We often talk about the idea of space, either physically or conceptually. But far less about time, how time is an omnipresent structure that is guiding each and every choice we make into alienation.

Could we start to imagine something as a “safe time”?12:00PM

Eat.

(If you’re hungry)

(Or not — it’s noon after all)1:11PM

Contemplate.

What an amazing time.2:30PM

Read the back cover of a book on your desk.Uncontained: Digital Disconnection and the Experience of Time by Robert Hassan.

“Author Robert Hassan believes we are trapped in a digital prison of constant distraction. In Uncontained, he books a passage on a container ship and spends five weeks travelling from Melbourne to Singapore without digital distractions — disconnected, and essentially alone.

In this space of isolation and reflection, he is able to reconnect with lost memories and interrogate the lived experience of time.”

3:32PM

Read a novel.Since the beginning of our research around the notion of time, I have been obsessed by the idea of adding a May 32nd to the festival. The idea comes from a novel by Simon Leduc, L’évasion d’Arthur ou La commune d’Hochelaga, but above all from the Nuit Debout movement which emerged in Paris in 2016. For Nuit Debout, time stopped on March 31st. And so Tuesday April 1st was renamed “March 32nd” and so on. “We will pass into April when we have decided!” shouted a man to a newspaper team. The very idea of being able to invent time seems absolutely necessary to rebuild our relationship with our day-to-day life.

5:43PM

Take your phone out of your pocket.

Check the time.

Put it back in your pocket.

Forget the time.

Repeat until you remember it.8:41PM

Think again.I’ve always been fascinated by the flaws and limits of translation, by the concepts and expressions that cannot be translated from one language to another, that get stuck in the perilous exercise of communication. For example, if you are trying to translate literally “What time is it?” in French, time would be translated as temps. But it wouldn’t work, because temps, in a question like that, would refer to the weather and not to temporality.

10:42PM

Look outside.11:59PM

Look at your clock and wait until it switches to 12:00AM.

Sleep.

About the Author

Festivals and The Time They Offer

Vincent de Repentigny’s text WHAT TIME IS IT? brought to light five key ideas on the notion of time:

- How “the concrete experiences of our lived times often seem out of sync with the abstract character of our clock-based social time regime” and how this can perhaps lead to alienation.

- Time on digital and online platforms as opposed to the lived experience of time.

- The idea of being able to invent new time structures.

- The notion of time as varying from one society and culture to the next.

- And time experienced differently as an individual and collective.

As co-director of performing arts festival Kyoto Experiment, all five of these ideas are very timely (!) when thinking about the present and future of a contemporary international performing arts festival, especially under the current circumstances we now find ourselves in. The performing arts sector, as well as the wider arts world and beyond, is experiencing numerous cancellations and postponements. At the same time, however, theatres and festivals offering online streamings of performances are more accessible than ever. Of course, the situation has had devastating effects, but viewed in a positive light, it has also forced many to reflect on current practices and brought to the fore a number of questions. One such question concerns the timescales and frames in which we organise and produce contemporary international performing arts festivals, as well as the timescales and frames in which audiences encounter these festivals.

In a world increasingly governed by productivity and an “obsession with saving, measuring and organizing time,” Repentigny’s imaginings of “safe time” or perhaps “non-productive” or “experimental” time is no doubt more essential than ever. Perhaps a way of achieving this “non-productive” time is by first delineating the boundaries of a “safe, non-productive space” in which one by definition spends their time being non-productive. Examples of this are perhaps public spaces such as libraries and parks, but we could also extend this idea to include public theatres and festivals. When there is increasing pressure to be productive, it is essential to advocate for as much freedom as possible in terms of the space and time in which work is produced and presented. This is, of course, important for the artist as well as the audience that encounters the work. In the future, we should increasingly think about how the festival as a platform can create and offer “non-productive” space in which not only artists but also audiences can spend “non-productive” time.

Performing arts certainly has the power to teach us new ways of discerning and experiencing space and time — in this sense, the power to invent new time structures. The “traditional” format for a performing arts festival consists of the presentation of a line-up of various artists’ works. The audience buys tickets, enters the theatre at 7pm, sits down, and “watches” the work. Perhaps, however, it is the responsibility of the festival, and not only the artist, to increasingly challenge these boundaries of space and time. A performing arts festival should not merely be about offering audiences performances to passively “watch” at a certain time, but also about creating time and space for artists and audiences, as well as the wider community in which the festival situates itself, to gather, and encounter and challenge one another. A festival, unlike a theatre tied to an actual immovable space, is perhaps fertile soil for experimenting with these ideas.

With regard to time as experienced in digital or virtual spaces, the increasing number of online streamings of performances has provided space for experimentation as well as a rise for concern about how the arts sector should protect the time- and space-bound “liveness” of the performing arts. Perhaps what is needed in the future is neither a full embrace nor a rejection of the digital in the performing arts sector, but rather a recognition and experimentation with the ways that the digital can give us more access to physical reality. This would not be a substitute for the experience of watching a live performance work, but instead a kind of second platform that could be provided by the festival. As Robert Hassan proposes, the mass of information online often seems like a “digital prison of constant distraction.” However, what if festivals could offer a well curated, independent online space, not to simply stream performances, but to invite and connect audiences internationally, giving an insight into the local scene, context, community, and processes that not only surround but sustain a contemporary performing arts festival?

The future of international performing arts festivals, as well as the performing arts sector more widely, certainly has much to consider when responding to contemporary notions of time and productivity. For festivals, providing a platform that can offer time for freedom in creation, encountering, and sharing between a community of people, artists, and audiences alike is essential.

About the Author

-

THE GLOSSARY OF MAGICAL PRACTICES, PLACES, AND CREATURES FROM SANTARCANGELO FESTIVAL, EDITIONS 2017-2019 as curated by Lisa Gilardino and Eva Neklyaeva (revealed full for the first time ever)