The Time of the Now

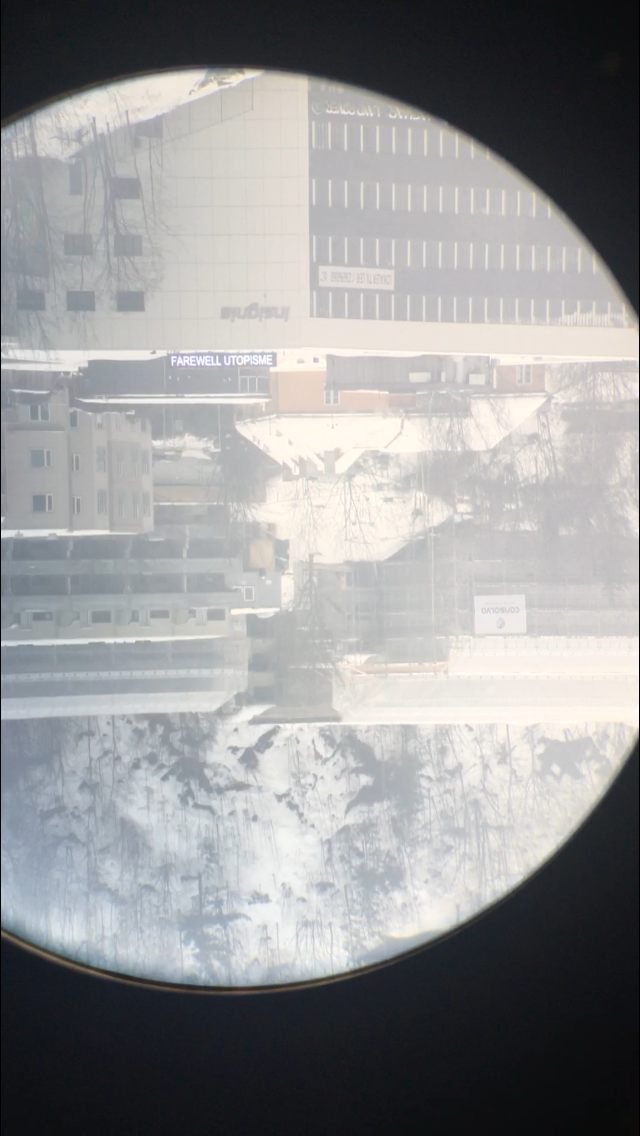

Dries Verhoeven, “Fare Thee Well!” (Oslo). Photo courtesy of the artist.

I am writing these lines after my first academic year at New York University in Abu Dhabi, one year after the last edition of Fast Forward, the site-specific festival that I imagined and curated for Athens as a critical response to the multifaceted “crisis” in Greece. I am writing these lines during a dematerialized summer shrunk to a disembodied liveliness and to a distanced sociality across space-times. While I am struggling to imagine a theatre that matters. As I always did. But now it seems that it needs to matter differently. It seems that it needs to address differently the urgencies that exist in the here-and-now, present but often latent, confined in between the anxieties of the creation time, the precarious conditions of the production system, the institutional imperatives, and the contested sponsorships. Does the fact that it needs to “matter differently” mean that we need to invent “new” forms and subject-matters? To challenge any exoticization through alienation? To decolonize originality and authenticity? To reconsider sustainability but also post-humanity? To privilege theatre as a social process instead of theatre as commodity? I honestly don’t know.

I am writing these lines as I need to imagine something in order to make it. Theatre is always, for me, a porous, relational common ground where discursive events go hand in hand with poetry and radical aesthetics. Theatre is a translocal space of togetherness, a collective state of mind where unimaginable forms of engagement and emancipation can potentially emerge. Theatre-as-commonality reminds us of the essential role that theatre has played in all times: from the ancient city-states to the struggles for freedom and justice in our “short century” and the ongoing fight for a world that matters — for all, equally.

I am writing these lines thinking that we need perhaps to unmake theatre in order to imagine it — to un-make means, Homi Bhabha writes, “to release from repression, and to reconstruct, reinscribe the elements of the known.”[1] Does that mean that theatre shall assume the responsibility for the unspoken? Shall we collectively envision cultural events that transcend the way that we have shaped our “global” art world? Could we rethink the role of the curator as a public servant at a moment when we don’t even know what “public” means? Is it possible to identify and dismantle the power relationships that shake the artistic field both on the inside and the outside? Shall we reconsider the distribution of resources beyond postcolonial concepts such as the Global South, or essentialist approaches to interculturalism? I honestly don’t know. I am only thinking that we need to re-imagine it.

[1] Homi Bhabha, “The World and the Home”, Social Text (1992, n. 31/32), 146.