In imagining a new theatre, my thoughts emerged as part curatorial dream statement, part personal manifesto, and part utopian fantasy:

I strive for a frame of curation where leading innovators working in time-based forms are given the same time, focus, and depth of historical and contemporary analysis that leading visual artists are regularly accorded by museums and by academia. In this world, the most challenging, opaque, and/or idiosyncratic performance work would get the kind of technical and financial support that mass-appeal entertainers receive without question. Multiple, ever-evolving contextual portals would be created in direct relationship with artistic production, attracting a wide range of audiences rewarded with deeper meaning and more profound experiences. Every project would involve extensive documentation, interpretation, scholarship, and archival strategies embedded from the start. The remaining institutional doors that limit artists’ access by geography, race, gender, discipline, or physical ability would be blown apart. Fellow national curators (myself included) would recognize when our own limitations of history/age/privilege were a barrier and step aside to let others more aligned with an artist or project take over. In this landscape, talented younger artists and curators would receive effective, thoughtful mentorship and training, while those more seasoned would acknowledge and draw inspiration from the energy and ideas of next-generation curators.

In my own curatorial practice, I’d finally achieve that perfect balance of offering deep support and rigorous critical response to the artists I work with, while also effectively translating their work to others, sparking intense curiosity and a shared passion about their creative work within a broad range of institutional stakeholders and regular citizens. I personally would aim for a more radical humility, where curatorial ego is dismantled (or at least diminished) and the power imbalance between artist and curator/institution is acknowledged and actively resisted. I’d better embrace personal dualities as well — bold yet modest, self-critical yet confident, impassioned yet studied, transcendent and epistemic, strategic yet conceptually daring. My practice would always be grounded in the etymological root of “care” in curation, nurturing living artists in their efforts to reinvent disciplines, combine forms, shift the dialogue, reanimate the public and take their place among the most important forces in this new society.

In this imaginary, utopic world, accomplished artists would be able to depend on systemic support for a lifetime of creative work rather than needing to constantly start afresh, attempting to make strong work amidst gnawing insecurity and financial instability. Binaries would be fully embraced — global and local; populist and esoteric; intimate and spectacular; conceptual and straightforward; academic and entrepreneurial; formalist and socially relevant; mysterious and highly rational; abstract and concrete; deep and broad. Artistic production and distribution would respond seriously to the vast climate and associated environmental crises, within which we seem to sleepwalk in denial. Artists and their curators/producers would help lead an essential societal transformation, inspiring other fields, rather than lagging behind, even if it means reimagining the energy-depleting movement of companies and productions, so long at the core to our fields. The artistic work of this imagined future, the ways of its making and the broader arts ecology, will offer solutions to how a surviving planet can transcend the treacherous politics we see today, addressing not just a non-carbon future, but also issues of racial justice and economic inequity. The philosophical, ephemeral, and at times improvisatory nature of live performance will offer essential structural lessons not just for arts but for how we sanely, and intuitively, devise rewarding individual and collective lives. Operating with fearlessness and joy, this artist-centered curatorial world would draw sustenance from the power of collective time-based artistic experiences, from the freedom and innovation offered by the artists of our time and of the future.

“If the good doctor can’t cure you, find the less good doctor.”

— Tswana Proverb

- In November 2015, internationally acclaimed South African artist William Kentridge gave a lecture entitled “Peripheral Thinking” at Yale University. In his talk, he raised the question of what is happening at the edges and how we can learn from it. He discussed the porousness of focus and described the ways in which studio processes can be instructive for looking at universal questions.

- In January 2016, I received a call at home in Johannesburg from Kentridge’s studio with a request to meet William for tea later that week. I had no idea what the meeting was about but remember waking up on the day of the meeting with a combination of curiosity and excitement. Later that day, I met a relaxed William just post his end-of-year holiday. He described a want to create and support a new space for the arts in Johannesburg. As a fellow artist, activist, and resident of downtown Joburg, he asked me to work alongside him and his studio team in initiating this space. The meeting was not very long, but I left it with formative words ringing in my ears: “interdisciplinary,”incubating,” “collaborative,” “collective,” “responsive,” “embodied.”

- In November 2016, I was in the eye of a magnificent storm of contemporary production.It was day three of an intense and massively generative five day incubator workshop working towards the inaugural performance season for The Centre for the Less Good Idea, due to open April 2017. Around 80 artists¹ from every discipline were being collectively curated by a five person team assembled by the Centre: a visual artist/filmmaker; theatre-maker/writer; poet/performer; choreographer/dancer; and composer/musician. We sought new combinations of text, movement, sounds and image. As we tested first ideas we hit upon incidental discoveries and had the opportunity to not only collectively identify and test them through repetition but to also capture the process, through film, sound, image and writing, an act of archiving fluid processes. The space was giving all its attention and resources to the impulses, connections, and revelations collectively identified by the artists.

- It was 4pm, and perhaps due to a late afternoon sugar low coupled with an unparalleled exhilaration, I had a sense of being outside of my body, a deja vu type of dream feeling — everything had slowed down, and I looked around the room: a group of poets and percussionists were responding by building sound and words to professional boxers in a boxing ring. A cinematographer and lighting designer were debating the best way to capture a visual artist furiously throwing clay and moulding it on to a dancer. An 11-man a cappella choir was moving in unison while a choreographer and operatic singer disrupted and responded to them. This was utopia, a safe making space for creative playfulness, and I was its animateur.Such a space doesn’t require a director in the traditional understanding of the word;it requires someone committed to maintaining energy and momentum, taking care of and holding artists in their processes, and pulling on threads and activating networks near and far.

- It is June 2020. The Centre for the Less Good Idea continues to be built in the same way one builds an artwork — through trial and error, piece by piece, allowing that which works to grow legs and letting that which does not fall away. If we had a manifesto it would be:²

- Sitting in the heart of downtown Johannesburg (a city famous for its violence and perpetual collapse),small and on the edge of the international art world is an incubator space for the performative arts. As founder and funder, William has allowed for an idyllic disregard for the usual economic logics of profit and gain which underpin so much art-making across the world. The collaborative collective approaches have, to date, given 400-odd artists over seven seasons and more than 30 one off performances an unparalleled momentum.

- So, what is next? We think, perhaps, an academy for the Less Good Idea?

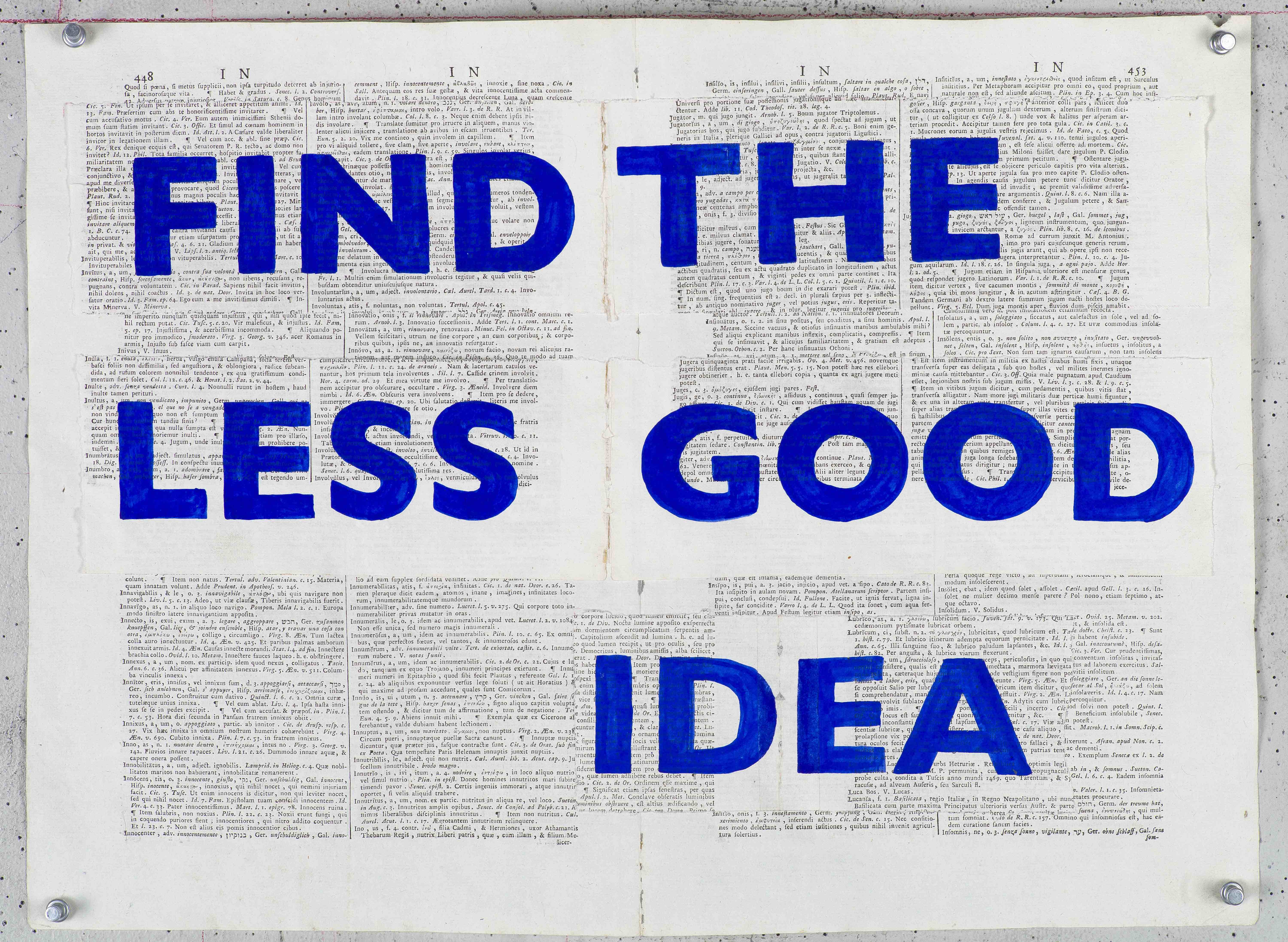

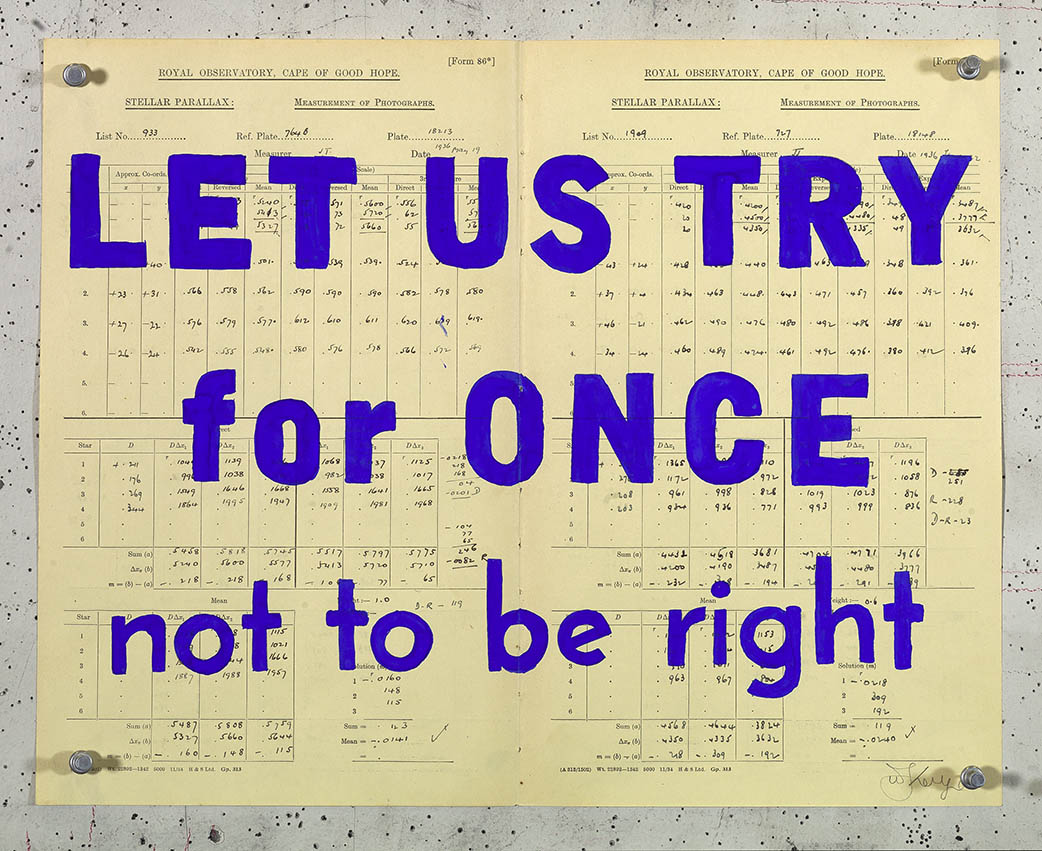

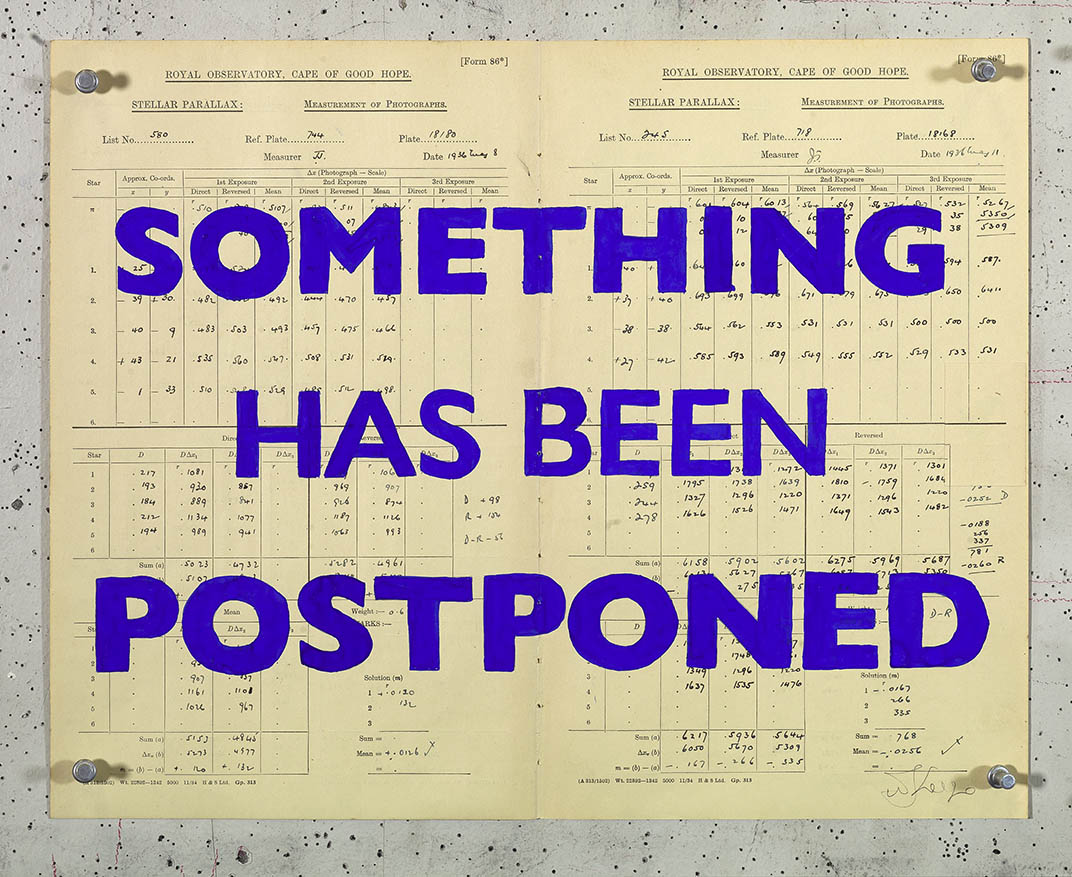

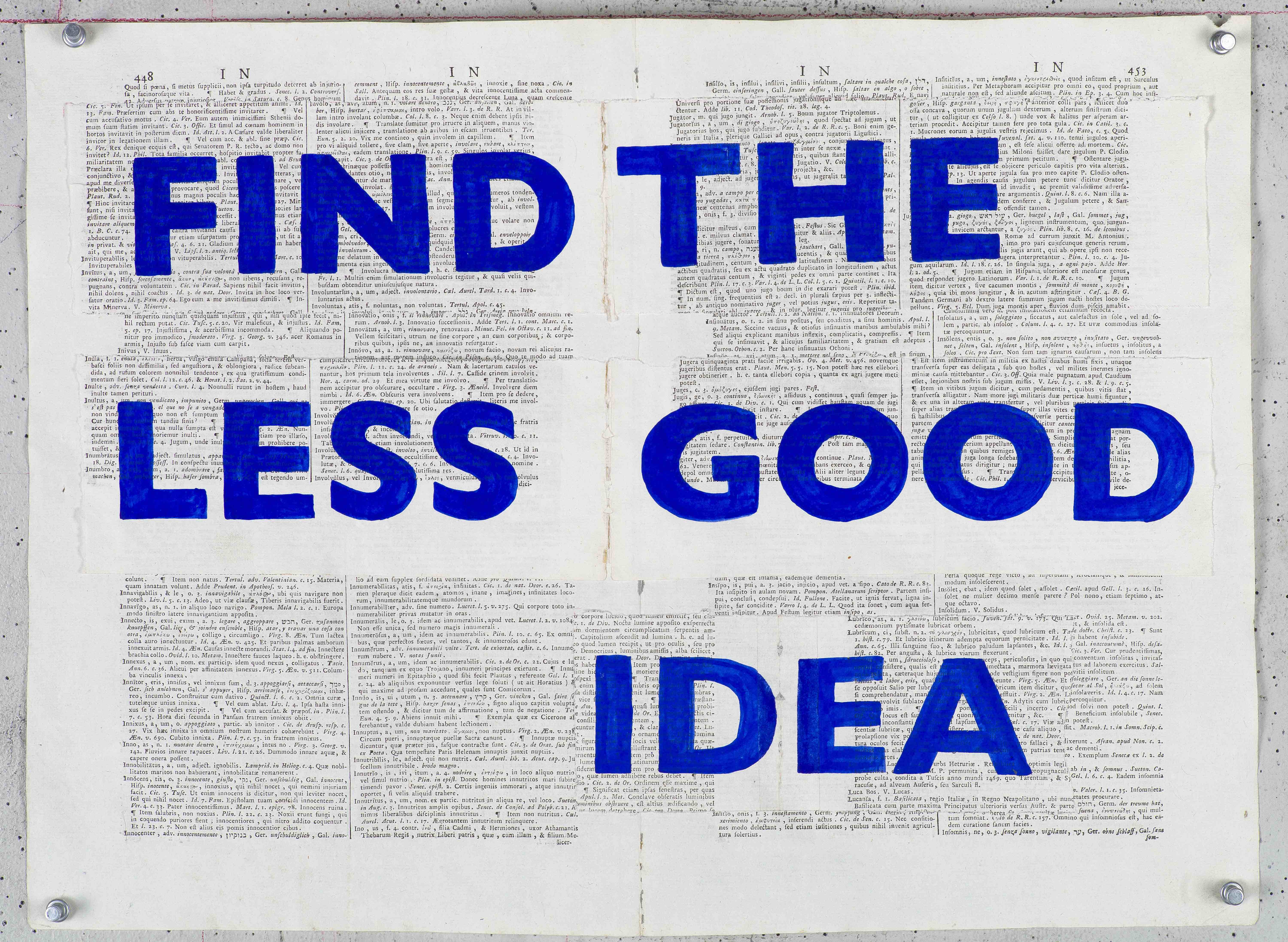

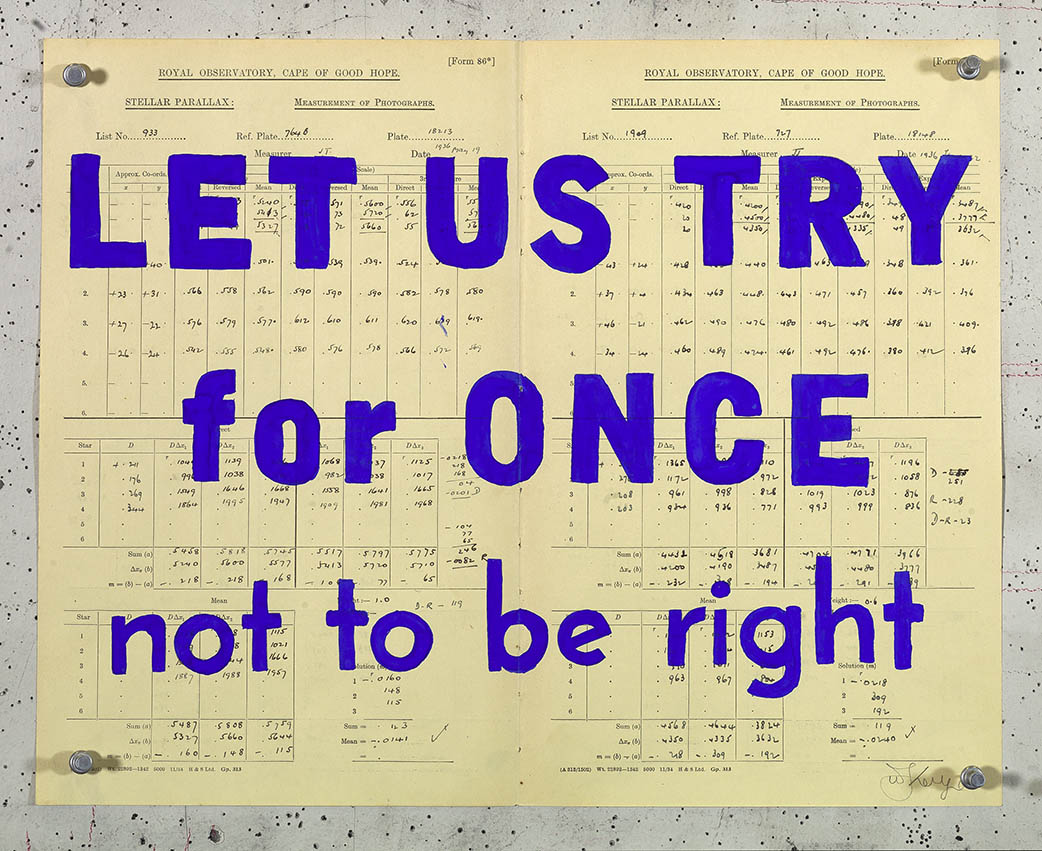

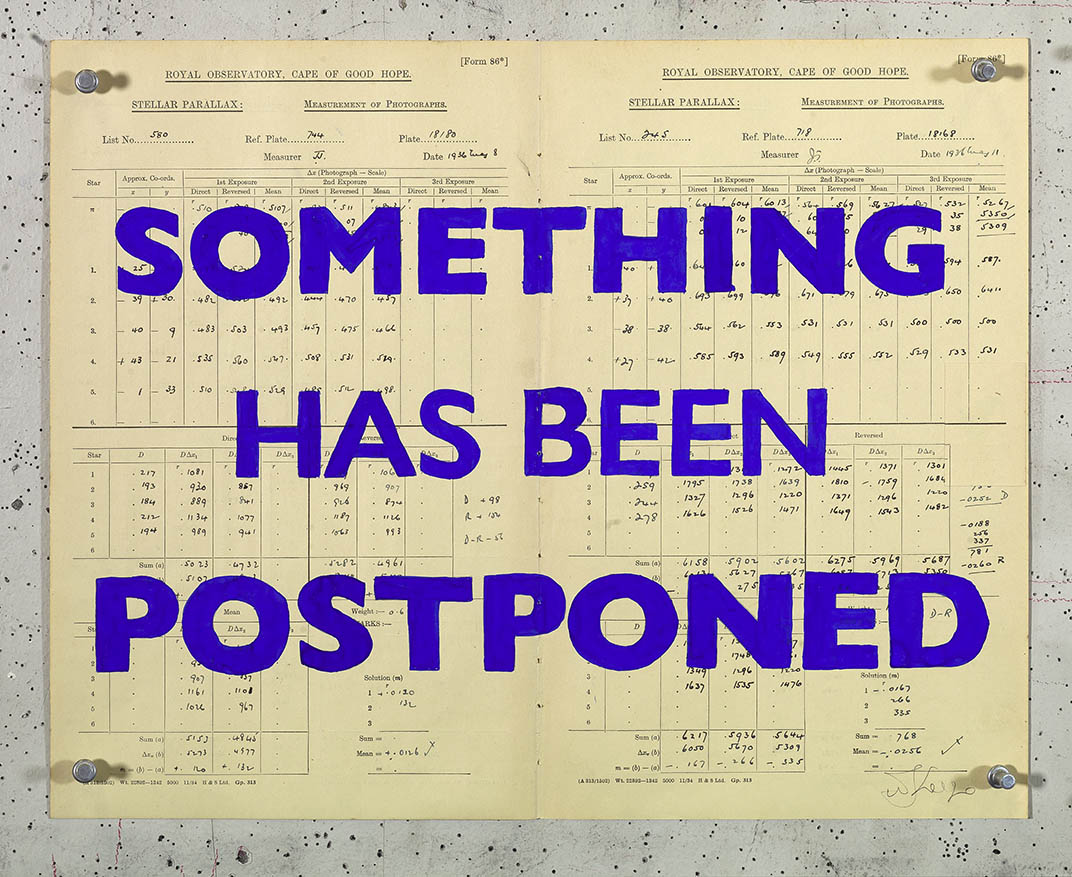

Photo credits: William Kentridge, Blue Rubrics, Lapis Lazuli pigment printed in blue on found thesaurus page.

1. The Centre creates two, six-month seasons a year. Core-curators from South Africa and of varying artistic disciplines are invited. The curators then engage practitioners with whom they would like to collaborate, and with that, the seasons grow. Alongside the seasons, the Centre has a monthly programme in which new work is incubated and shown for one night only. In 2020, we launched SO, the Academy for the Less Good Idea.

2. The Centre’s visual and conceptual identities are drawn from William’s practice, in particular his methodological approach to generating new large-scale performance work. Visually, our identity is based on his Blue Rubrics, a series William began after receiving a gift of pure lapis lazuli gouache from Afghanistan. In order to find a use for the vivid blue pigment, he addressed it in terms of its specific color and material. eventually mixing it into ink to overlay silkscreen prints. In William’s words, “They are called Blue Rubrics, but a rubric really should be red — a rubric was the printed or illuminated red text in a liturgical manuscript, in which the black ink would have been the text of the liturgy and the red would have been instructions on how to pray. So they are footnotes to a thought, the edges of the thought. In my case, they are unsolved riddles, phrases which hover at the edge of making sense… WHO NEEDS WORDS (the whispering in the leaves)…. These are fragments of sentences which sit in a drawer of phrases used in other work over the years, which get taken out and sorted through on occasions.”